By Michael Karadjis

The fall of the Assad regime on December 8 2024 was a belated culmination of the revolution which began in 2011, an extremely broad, diverse, democratic revolution; however, long before this, by around 2016-18, this revolution had been largely crushed or confined by the Assad regime’s genocidal terror. Years of repression, stalemate, despair and exile followed.

As Syrian writer Robin Yassin-Kassab described it just before the December 8 victory:

“The civil revolution that began in 2011 was largely crushed, its experiments in democracy eliminated, its most grassroots military forces co-opted or gobbled up by more powerful and authoritarian actors. There are no longer hundreds of independent, quasi-democratic local councils to organise civil life. The country is divided, traumatised, cursed by warlords and foreign occupiers. But suddenly it looks as if it may be possible not only to challenge but to end the rule of the monster …”

Hence as the regime, with the decisive aid of Russia’s air war and Iranian-backed Shiite sectarian militia, drove back the revolutionary forces, the only remaining areas free of Assad in the northwest came under the hegemonic control of either the Turkish regime, or of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the hardline Islamist militia then led by today’s president Ahmed al-Sharaa. While there were sharp differences and armed conflicts between the Turkish-backed groups and HTS, both Turkish and HTS hegemony in their own ways were negative influences from the perspective of the democratic revolution that they were coopting.

This is the background to HTS emerging as the leading force in November and December 2024 – the opposite of the situation 2011-2017, when HTS’s predecessor, Jabhat al-Nusra, was only one of countless rebel forces; and the opposite of the expectations of the vast majority of Syrian revolutionary forces since 2011.

Background to HTS

Here it seems a little background on HTS would be useful. Jabhat al-Nusra arose in 2012 as a Sunni sectarian militia which affiliated to al-Qaeda (its leaders like al-Sharaa had been veterans of al-Qaeda in Iraq who took part in the Iraqi resistance against US occupation), and its reactionary and repressive politics were anathema to the goals of the revolution. However, following its rejection, in 2013, of the attempt of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) – which had quit al-Qaeda – to impose itself on Nusra in the form of ISIS, an important distinction arose: the more Syria-based Nusra, which focused on fighting the regime, often bent to the pressure of the people and other rebel factions, while ISIS from the outset was an outright enemy of the revolution, much more so than it was ever an enemy of the regime (indeed, both the regime and ISIS always focused more on fighting the rebels than each other, often enough at the same time).

Therefore, from a purely military standpoint, the vast array of Syrian rebel groups, representing a wide variety of ideological perspectives, were usually in some kind of united front situation with Nusra against the far more powerful genocidal regime and genocidal ISIS. In 2016, the Nusra leadership split from al-Qaeda as well, and in early 2017 formed HTS with a number of smaller Islamist factions to focus on Syria rather than connections to ‘global jihad’.

Despite this convergence of interests, Nusra, and later HTS, also worked to monopolise the situation where it was strong, and would sometimes destroy other rebel formations which threatened its power. This was not always successful though, and vast rebel-controlled coalitions and regions resisted Nusra or HTS encroachment and at times imposed important defeats on them.

However, the regime’s victories aided the process of HTS hegemonisation. The crushing of free Aleppo in late 2016 – where Nusra had been only one of 40 odd rebel groups – and of a number of famous revolutionary towns such as Daraya and Moademiyah around Damascus in 2015-17, and then the reconquest of the south from some 50 democratic rebel groups (the FSA Southern Front) in 2018, left only the northwest under rebel control. But in the huge regime and Russian offensives between 2018-2020 in the northwest, all the famous revolutionary towns with a strong revolutionary-democratic tradition, and a hsitory of resistance to Nusra/HTS encroachment – Saraqeb, Kafranbel, Maraat al-Numan, Atareb and so on – were conquered by the regime, hugely weakening the more independent, non-HTS sectors, and driving everyone into a corner near the Turkish border – either Idlib under HTS control, or the northern border regions under Turkish control.

So, while in the 2012-17 period, Nusra’s 10,000 fighters never formed more than about 10 percent of the rebel fighting force, HTS was estimated to have some 35,000 fighters when it launched its late November offensive last year. When these revolutionary towns in the northwest were conquered in 2018-20, their populations fled to remaining free territory, controlled by HTS, and many people not previously associated with it joined its fighting ranks. According to Ayham al-Sati of Baynana, a Spanish-language media outlet founded by Syrian journalists, “Many of the people who are now fighting … are children of areas like Saraqeb or Kafranbel. We are seeing figures we recognise from 2011, who then fought a regime that was bombing its population, and now they are doing it again.” Even troops from FSA brigades earlier destroyed by Nusra later joined HTS ranks, as their main aim remained the fall of the regime and this had become the last effective fighting force.

It should also be noted that the HTS-led ‘Deterrence of Aggression’ offensive in November 2024 also included a number of Free Syrian Army formations, most notably Jaysh al-Izza and the National Front for Liberation, which had managed to maintain a degree of independence from both HTS and the Turkish-controlled Syrian National Army (SNA). While having ideologically little in common with HTS, in practice they became closer to HTS simply because it continued to fight the regime, whereas the SNA was largely used by Turkey as an anti-Kurdish proxy while the Erdogan regime appealed to Assad for joint action against the Kurdish-led SDF, and as such aimed to keep the peace in the northwest.

But this meant that, while on one hand, HTS monopolised the fighting forces, the impact also went the other way, because the huge growth of HTS meant the vast majority of its cadres were never in Nusra, and therefore never connected to al-Qaeda. And these influences by non-Nusra elements, as well as the simple needs of technocratic governance in Idlib for 8 years, had a serious moderating impact on HTS, which was vital to its ability to lead the revolution in December.

This underlines the fact that HTS was essentially a coalition, and cannot be easily defined by the original Nusra core group. It includes pragmatic elements, hard jihadist elements, elements closer to the revolutionary-democratic traditions of the revolution and so on. Discussion on whether HTS’s transformation is real or superficial often takes on essentialist forms (absurd statements like “al-Qaeda can never change”), yet there have been marked changes over last few years in Idlib itself, including outreach to Christian and Druze communities which Nusra had severely oppressed, as well as to Kurds and to the SDF.

However, these genuine changes in HTS do not mean that it ceased being an authoritarian Sunni Islamist group, and in any case a significant part of its base still consisted of ideological jihadists. Reports by human rights organisations consistently reported on repression and torture used in prisons (although by then the majority of prisoners were unreconstructed al-Qaeda or other hard-jihadist militants rejecting HTS’s pragmatic course); and Syrian revolutionary activists remember that some of their outstanding cadres, such as Raed Fares and Hamoud Juneid, are widely believed to have been murdered by HTS cadre.

Nusra/HTS, in other words, was long a known quantity, and was previously the very last choice of Syrian revolutionaries to be the leadership, but hard reality changed things.

‘Deformed revolution’ or mere ‘popular coup’?

What accounts for such a rapid collapse of the regime? The main cause was that it was hollow; its troops refused to fight; no soldier in Syria thought they should put their life on the line for the rotten, uber-corrupt, thieving, tyrannical regime. But there was a second factor, and this was the ability of this more pragmatic HTS to realise that, to carry through this revolution, it was required to do and say things which stood in stark contrast to its background, ideology and practice in Idlib, for example outreach to all religious and ethnic minorities, promises to women of no compulsory veiling and so on. The revolution would not have been possible without this – even people who hated the regime may still have resisted if they believed HTS was still what Nusra had been a decade earlier.

The regime’s previous crushing of the revolution and all its popular organisations, combined with its utter hollowness, meant that it simply collapsed once the HTS-led “Deterrence of Aggression” offensive took off, so the rebel army simply took power, but without a mobilised and organised revolutionary population taking part. While some observers, such as Gilbert Achcar, have claimed that this was therefore not a revolution (indeed he warns against characterising it “as the resumption of the Syrian revolution”), in my view this lacks a huge amount of nuance; millions of Syrian people did come out and welcome the rebels everywhere, and countless popular initiatives began to take shape, and in their consciousness the masses feel it as the culmination of what they began. Nevertheless, it means that the new government, while based on popular support, is under less restraint from the revolution’s base than it would have been otherwise, and the new state’s armed forces were de facto almost entirely Sunni Muslim in composition.

Rather than a mere ‘popular coup’, what occurred is better analysed as a ‘deformed revolution’.

A capitalist regime, a democratic opening and a devastated country

To state the obvious, the Islamist-influenced government led by al-Sharaa is a capitalist one; no-one had ever imagined anything different. And the cadres around the former HTS seek to consolidate their own power as the leading political force in this government. A capitalist government, whatever its political colouring, will aim to stabilise the situation for local and foreign capital, and to sideline any radical, working class or socialist challenge to its rule.

At the same time, December 8 created a semi-revolutionary situation: the Syrian masses who entered the streets in December have expectations, they are pressing their demands. Above all, democratic space now exists that did not exist before December; the masses are able to speak, to organise, to hold rallies and meetings around the country without being repressed. This is a vastly different situation for organising – and only now is there some possibility of attempting to establish a workers’ movement. Previously you would have ended up in the Sednaya concentration camp or in a mass grave.

Yet both of these generalisations, these truisms – ‘capitalist government’ and ‘democratic opening’ – need qualification. The fact is, Syria, emerging from 54 years of tyranny and 14 years of genocidal war, is a destroyed country. Entire cities, parts of cities and towns have been razed to the ground by years of Assad regime and Russian bombing. Ninety percent of the population live in poverty. Syria ranks as the fourth most food-insecure nation on Earth. Half of Syria’s water systems are destroyed. A 2017 World Bank report estimated that nearly a third of the housing stock and half of medical and education facilities had been damaged or destroyed by regime bombing; two and a half million children are now out of school (among Syrian refugees in the region, half are under 18 and one third of them do not have access to education). The US sanctions imposed on the Assad regime devastated the civilian population rather than the regime cronies, who amassed fabulous wealth; the country was further impoverished by that regime’s massive theft from the population. Some 6.7 million Syrians – of an original population of 23 million – live in exile abroad, while a similar number are internal refugees, together accounting for 60 percent of Syria’s population; 2 million live in tents in Idlib and Aleppo regions. While 482,000 have already returned to Syria since December, on top of 1.2 million internal refugees who have returned to their homes, the main thing continuing to hold up return is the sanctions, because there is no capacity to begin reconstruction of the homes of these millions. While tens of thousands were released from Assad’s torture gulag in December, some 130,000 remain unaccounted for, slowly being dug out of mass graves, a fraction of the 700,000 killed in the genocidal war.

Currently there is electricity for a few hours a day, if lucky, food and fuel are absurdly expensive due to being in very short supply, and wages abysmal, the state bankrupt – so bankrupt that Qatar and Saudi Arabia paid off a mere $15 million in debt to the IMF and World Bank that the government could not afford. With the central bank sanctioned, virtually no banks around the world have been able to make financial transactions with Syria; not even remittances could get through much of the time. Even a Qatari attempt from January to pay public sector salaries for a few months was held up by US sanctions until May, when special permission was finally given by the US (except for military and security salaries).

Clearly, no reconstruction can occur without the lifting of sanctions. And there can be no illusions about a working-class or socialist movement in the short-term without some level of recovery of industry, infrastructure and of the population.

And in the real world, getting the economy going again, bringing about reconstruction, will require massive injections of local and foreign capital, loans and aid. While “stability for investment” may be goal of a capitalist government, at this moment it also equates with the popular mood and with the needs of the country and its population. The sanctions not only devastated the population, they also further demobilised them, both under late Assad and post-Assad, given their everyday struggle for survival.

Of course, capitalist investment and economic activity are no panacea, but currently it would be a luxury to worry too much about this in the context of the absence of any money for investment and development; Assad’s kleptocratic crony capitalism was little more than a regime of plunder, and its collapse has left nothingness in place of it. Capitalist investment and an onset of economic recovery would create conditions for class struggle to revive, to confront the evils that capitalist investment will re-introduce in a new form.

A capitalist government with an unclear direction

Which direction does its need to establish a stable capitalist regime lead the ex-HTS core group now in effective control in Syria?

- Towards continuing with its pragmatic liberal-capitalist transformation, and opening further in a non-sectarian direction towards the countries’ minorities?

- Or to reasserting its more ‘Islamist’ character, imposing a hard Sunni Islamist regime, as a means of repression, and asserting Sunni sectarianism as a means to suppress minorities? The Sunni version of what happened in Iran.

The jury is still out on this; both pressures and tendencies exist. To date, while the government has mostly gone in the first direction, there have also been signs of the second. Either way, it has tended to appoint many people from former HTS or closely allied groups to key political and military-security roles in the caretaker government – critics call this ‘one colour’ appointments – and has somewhat limited the move towards democracy at an institutional level, while maintaining a generally pragmatic course and environment of free expression. These are some of the major changes:

- At a conference of armed factions in January, the rebel militia were told to dissolve – including HTS itself – and form a new Syrian army. However, there has been little real progress in fully integrating the factions, especially some of the SNA factions who carried out terrible crimes in March on the coast (see below). Moreover, this underlines a fundamental problem/weakness with the new regime: given that the overwhelming majority of rebel cadres, especially by late in the conflict, were Sunni Arabs, this means the the regime’s main armed forces are essentially from this one dominant part of the population. While this is an inheritance rather than a deliberate policy, there has been very little movement to expand the military to incorporate minorities, a fundamental issue when the army is used in non-Sunni areas, given the deep divisions inherited from the Assad regime.

- This conference also declared al-Sharaa interim president. While this was arguably formalising a reality, he was thereby declared president by a purely military gathering representing only one section of Syrian society.

- The long promised National Dialogue Conference in March did not live up to its promise – the committee appointed to organise it was small and dominated by supporters of the ruling group; the basis upon which delegates were selected at local gatherings was opaque; invites to the conference were sent out only two days beforehand, preventing many long-time Syrian revolutionaries abroad from reaching it; the conference lasted only a day; and its decisions carry little weight.

- The government declared it would take four years to write a new constitution and five years to hold elections. Some period of time for recovery is understandable, and millions of Syrians abroad or internally displaced should also be able to take part in decision-making; and in any case, holding elections now would most likely simply lead to al-Sharaa being elected and strengthened. However, these periods of time are widely considered rather long.

- The interim constitution declared in March, to be in effect until a new constitution is written, declares ‘Sharia’ to be the major influence on Syrian law, and that the president must be a Muslim. While these aspects represent formal continuity with the Assad regime constitution, people expect the new Syria to go beyond the old regime; moreover, some fear that these clauses may be used undemocratically by an Islamist-influenced government where they were not by the secular-fascist Assad regime, which justified totalitarian rule using different ideological constructs. The interim constitution also gives sweeping powers to the president, allowing him to appoint one third of the national assembly. However, many aspects were better, including clauses guaranteeing “the social, economic and political rights of women,” protecting “freedom of belief and the status of religious sects” and guaranteeing ”the cultural diversity of Syrian society, including the cultural and linguistic rights of all Syrians.”

- The new transitional government appointed in April emphasised technical expertise, and of 23 members, only four had been members of HTS and another five associated with it at some level; this was thus an improvement on the one-colour interim cabinet. Respected civil activists such as Hind Kabawat, who has a background in Syria’s civil opposition movement, and Raed al-Saleh, head of the White Helmets disaster relief and rescue service, were included. However, there is only one woman, one Alawite, one Druze, one Kurd and one Christian (Kabawat, who is also the woman!), as opposed to 19 Sunni Arab men, so this attempt at diverse representation smacks of tokenism. Five ministers previously served in senior positions in the Assad regime, including the two main economic-related ministers, who not surprisingly are advocates of neoliberal policies.

When government ministers have made unacceptable statements or decisions, there has been pushback, often leading to retreat. For example, when announced school curriculum changes (including scrapping evolution) were widely protested, the government said they were only suggestions, and that the only actionable change was the removal of Assad worship; Syria’s caretaker prime minister, Mohammed al-Bashir, appeared in front of a flag that displayed the shahada (Islamic profession of faith) as well as the Free Syrian flag, but following a storm of criticism, at his next public appearance only the revolution flag was present.

Significant demonstrations and public meetings were held by women to protest the anti-woman agenda put forth by two HTS appointees. Thus far, there is little evidence of this agenda being implemented, despite worrying signs. The governor initially appointed for Suweida province was the first woman in Syria’s history in that position. When asked about women’s rights to study and work, al-Sharaa pointed out that in Idlib under his government, women are 60 percent of university graduates. Given what happened to women’s rights under an Islamist regime following a popular revolution in Iran, women’s movements will need to stay alert.

There have been plenty of declarations by small groups of leftists, workers organisations, other progressive groups and the like around various issues, but it is hard to gauge how significant they are. There is no room for exaggeration on this – after 54 years of monstrously repressive rule, it is going to take some time for workers and leftist movements to emerge in a country destroyed. There have also been many local grassroots initiatives, eg local people began organising their own people’s security forces in Aleppo; a popular initiative there quite early put the demand on HTS and the other militia to leave the cities to local councils, and they agreed; non-governmental civic councils in parts of Daraa and Damascus monitoring local government and services; grassroots local councils in the Qalamoun region supporting education and aid initiatives for displaced people; grassroots re-greening initiatives in Daraa; inter-communal dialogue initiatives between Sunni and Alawite communities taking place on the coast; and much more. Again, however, this is mostly small-scale.

Neoliberal orientation – and Assadist connections?

In January, the government announced an economic policy based on free markets and privatisation of ‘loss-making’ state enterprises, while maintaining critical infrastructure in state hands. An article in the Financial Times was headlined ‘Syria to dismantle Assad-era socialism, says foreign minister’, referring to Shaibani’s speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos, demonstrating the way the new government aimed to get needed foreign investment by propagandistically playing up its rejection of the so-called ‘socialism’ of the Assad regime.

However, while the new government certainly is neoliberal, there should be no illusions about the role of large-scale private capitalist ownership under the Assad regime, largely owned by Assad family and regime-connected cronies. For example, again from the Financial Times, Assad’s cousin, Rami Makhlouf, controlled “as much as 60 per cent of the country’s economy through a complex web of holding companies. His business empire spans industries ranging from telecommunications, oil, gas and construction, to banking, airlines and retail. He even owns the country’s only duty free business as well as several private schools. This concentration of power, say bankers and economists, has made it almost impossible for outsiders to conduct business in Syria without his consent” (ironically given the ‘socialism’ title in the article above, the Financial Times here cites another of the same paper’s articles entitled ‘Syria sees benefits of liberalisation’, referring to the Assad regime!). Moreover, much of this “complex web” extended into what is euphemistically called the ‘state-owned economy’ via massive corruption and nepotism.

On top of this, foreign investment is hardly new; after all, Russia and Iran owned large chunks of the Syrian economy, and even became rivals for control of the Syrian corpse. Russia owned phosphate mines, ports, gas fields and so on; Iran amongst other things owned much of the telecommunications network. These deals were often not on terms beneficial to Syria. Whatever the case, this collapsed with the regime.

As such, Syria’s new quest to mobilise local and especially foreign capital is not so much a change as a step to the side; Shaibani’s talk of Assad’s ‘socialism’ pure opportunism to encourage western investment. Ironically, the government actually cancelled a 49-year contract over a Tartous port held by the Russian navy in the same week as Shaibani’s speech in Davos; Syrian authorities said that revenue from the port would “now benefit the Syrian state,” whereas Russia had received 65 percent of the port’s profits in the old agreement, meaning Syria basically carried out an act of nationalisation, of ‘socialism’, just as Shaibani was talking up rejecting ‘socialism’!

All that said, the continuity of neoliberalism means anti-worker policy. The government has called for the retrenchment of some 400,000 of the 1.3 million-strong public sector workforce; some of this has either already been implemented, or workers were placed on three months of compulsory leave (whether paid or unpaid remains unclear) while authorities assess whether these jobs are needed. The excuse given is that these are just paper jobs created by the previous regime to pay its cronies and supporters for doing nothing; while this claim should not be dismissed out of hand, rather than trusting capitalist governments to deal with such issues, they should be investigated by unions or workers’ committees. Of course retrenchments are hardly surprising in a bankrupt economy, after losing the lifelines provided by Assad’s Russian and Iranian allies, which until May were not replicated even by Syria’s new friends due to US secondary sanctions. There have been strikes in health and education and other sectors against lay-offs. On the other side, in late June, Sharaa issued a decree raising all public sector salaries (as well as those of employees in joint-ventures), and pensions, by 200 percent, thus raising the average wage from $40 to $120 a month; this is the first step in a promised 400 percent increase.

The beginnings of sanctions removal following Trump’s mid-May about-turn is of course a hugely welcome change, but at the same time there can be no illusions about what a massive influx of local and foreign capital will do politically. On the one hand, it is important to re-emphasise how essential this is. Already, major French, Chinese, Turkish, Qatari, Saudi and Emirati projects have been launched, focused on restoration of Syria’s crucial infrastructure and energy sectors.

However, as Syrian writer Joseph Daher stresses, an economic free for all without clear targets will not lift the country out of its misery, especially given the government’s neo-liberal orientation; he also stresses the necessary political dimension of democratic inclusion and revival of civil activism to assuring the gains are not all made by big capital, otherwise the government’s already centralising tendencies could drift towards what he calls “authoritarian neoliberalism,” which is essentially what the Assad regime, like the other regional regimes, had become and was precisely what led to the revolution – with the proviso that “authoritarian” is a rather euphemistic term to use for a regime as totalitarian and genocidal as that of Assad and it would take massive anti-democratic setbacks for this new order to even begin approaching that scenario.

One thing the Assad regime did leave was some fabulously wealthy individuals, and these Assad-connected capitalists may be grabbing some of the new investment opportunities. As Syrian writer Mahmoud Bitar notes, “Russia and Iran are not standing aside. Their economic arms, state-linked contractors, businessmen, and cronies are still embedded in Syria’s reconstruction, energy, and infrastructure sectors. … The likes of Mohamad Hamsho, who controls hard currency flows, and Fuad al-Assi, who runs the country’s largest money transfer network, remain central players … Lifting sanctions could make them stronger tomorrow.” As a party calling itself the Syrian Democratic Left Party notes, new investments will only contribute meaningfully to recovery if protected from entrenched corruption inherited from the former regime, requiring a new regulatory framework.

Shortly, after writing these lines, Bitar returned to the largest and most important showpiece of the post-sanctions climate: the $7 billion investment in power infrastructure by the Qatari-led UCC-Holding and Power International consortium, expected to provide some 50 percent of Syria’s power needs and to create 50,000 direct and 250,000 indirect jobs. While the importance of this for Syria can hardly be doubted, Bitar notes that these two linked companies are owned by Moutaz and Ramez Al-Khayyat, who were also behind a 2005 “disastrous Ummayad Tunnel project in Damascus” which was carried out “in partnership with the Military Housing Establishment, one of Assad’s most notoriously corrupt state fronts.” Moreover, he notes that the Al-Khayyat brothers are nephews of the very Mohammad Hamsho he had just mentioned, who was “the Assad regime’s top economic operator, still active and protected in Damascus despite international sanctions.” Bitar also questions why the consortium is not investing in the 14 existing power plants, rather than “building 4 new ones from scratch.”

Bitar also revealed that Farhan al-Marsoumi, “a key figure in Assad’s Captagon production and smuggling networks, has received a license from the new Syrian government to open a tobacco company.” Aside from his Captagon trade, he was also a key Iranian-connected figure in Deir Ezzor , who led recruitment efforts for Iran’s 47th Regiment, and was even connected to Maher al-Assad’s notorious 4th Brigade.

Capitalism is clearly a key point of connection between the previous and current regimes, and if these examples become the norm, we may be seeing the resurrection of elements of the old regime by stealth.

Interestingly, al-Sharaa’s economist father, Hussein, strongly criticised the privatisation push, declaring the state sector a “national asset built over decades,” and claiming that “the issue is not with the public sector itself, but with the mismanagement that has plagued it.” He warned that privatisation posed both ‘sovereignty’ and economic issues.

Transitional justice or lack of it

Al-Sharaa issued a decree on May 17 for the establishment of a Transitional Justice Commission, tasked with “uncovering the facts regarding the violations of the former regime” and to “hold accountable those responsible for the violations … and redress the harm caused to victims and consolidate the principles of national reconciliation.” On the same day, a National Authority for Missing Persons, to be responsible for “investigating and uncovering the fate of the missing and forcibly disappeared and documenting their cases,” was also established.

However, to date the Syrian people have seen virtually no evidence of this justice in action, and even the formal establishment of this commission was considered months late by the public. On April 25, Syrian activists had called ‘Friday of Rage’ demonstrations around the country under the slogan ‘Transitional Justice and the Beginning of Trials.’ This demonstrated the depth of anger at the lack of accountability of the Assad-era criminals responsible for hundreds of thousands of killings and untold destruction. Interior Ministry spokesman Nouruddin al-Baba confirmed that 123,000 former regime personnel were implicated in crimes against Syrians.

The lack of a ‘transitional justice’ process in the months since December is widely cited as a factor driving on-the-ground retribution against perpetrators, assumed perpetrators, or in the worst cases, collective ‘retribution’ against Alawites. Thus while the security forces can in some cases be blamed for being too harsh on the Alawite communities when searching for Assadist criminals, this goes hand in hand with the government being too soft on these criminals in the bigger picture. So, on the one hand, there was a sweeping amnesty of ordinary Assadist troops and security forces; tens of thousands of troops passed through government “resettlement” processes to demonstrate their innocence. This is of course a very good measure of the new government. However, while a very significant number of Assadist war criminals have been arrested, none have faced the judiciary yet, which casts the actual positive measure in a negative light to many victims. The amnesty is aimed at engendering social peace, but the lack of accountability for actual criminals engenders the exact opposite.

What has made it much worse is that in some cases even worse Assadist criminals, unaccountably, now walk the streets. For example, Fadi Saqr, former National Defence Forces (NDF) leader who shares responsibility for the horrific Tadamoun massacre, was inconceivably amnestied, leading to protests; war criminal Ziad Masouh, responsible for massacres in western Homs region, was released from prison; Khaled al-Qassoum, head of the Shabiha ‘Popular Resistance’ militia and close associate of the ‘Butcher of Baniyas’ Ali Kayali, returned to live in Hama city with security guarantees! In some cases the explanation is that is that these Assadist generals made last-minute deals and stood aside in December, ensuring the surrender of entire territories without causing unnecessary bloodshed. This has created huge resentment among Syrians whose families were slaughtered and homes and cities destroyed.

However, Information Minister Hamza al-Mustafa claims the releases are provisional, prioritizing short-term stability while pledging long-term justice. Thus civil peace efforts, including community reconciliation, are precursors to formal justice, as “a turbulent atmosphere guarantees neither fair trials nor reparations.” He referenced post-apartheid South Africa’s model, where truth-telling preceded prosecutions. At a June 10 press conference, Hassan Soufan of the Civil Peace Committee claimed the government’s “amnesty-centered approach” had helped sharply reduce [Assadist] insurgent attacks since March.

Whether this works or not is unclear. In Homs, a former Assadist commander was killed on April 20, and the assassin appeared on video complaining he had raised charges against him related to crimes against civilians, to no avail, so he acted himself; and in Aleppo, a militia calling itself the Special Accountability Task Force was launched on the same day, by former rebels take the law into their own hands and assassinate former Assad regime criminals. Such initiatives are inevitable in the circumstances; but though they appear directed at actual criminals (Alawite and Sunni alike) rather than Alawite civilians, there is huge potential for this to go wrong. According to Gregory Waters, such vigilante executions “surged” following Soufan’s June 10 acknowledgement that Fadi Saqr had been given a role in the committee as a key intermediary with ex-regime insurgents and loyalists, a kind of “peace-builder” whose safety is “guaranteed” by the Committee!

Much worse is the appearance of a new Sunni sectarian militia, Saraya Ansar al-Sunna, which has essentially declared war on the country’s minorities, which made its appearance by killing 15 Alawites in Hama in February. Unlike ISIS it has not yet militarily confronted the government, but it has issued fatwas against al-Sharaa’s “tyrannical” government, declaring them infidels. While such an ideologically reactionary militia cannot be blamed on lack of transitional justice, it may well be able to recruit from some disaffected by it.

More generally, the lack of transitional justice (and perceived betrayals of it), combined with the lack of jobs in sanctioned post-Assad Syria has also been a factor in the prominence of jihadi-inspired armed civilian groups which played an important role in both the slaughter of Alawites in March, and the attacks on Druze in late April-early May, to be discussed below.

How much does the government control?

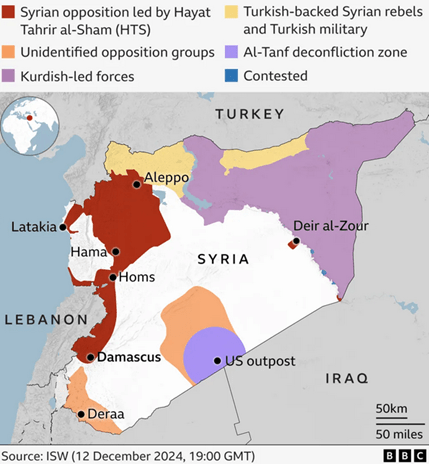

A few tens of thousands of troops that HTS and its allies had may have been adequate as a security force for the northwest corner of Syria, but once in control of a country of 23 million people, it is in a weak position. The government currently only controls part of Syria, most of the Sunni Arab heartland running down the west of the country from Idlib and Aleppo in the north, through Hama and Homs, down to Damascus. Regarding the rest of the country:

- South of Damascus, the also Sunni Daraa and Quneitra provinces came under the control of old Free Syrian Army (FSA) Southern Front brigades, some of which joined the new army while some resisted; however, the main militia resisting integration, the formerly Russian and UAE-backed 8th Brigade, finally dissolved in April, an important victory for the government, so formal government authority now extends to these provinces.

- The neighbouring Druze-majority Suweida province is somewhat autonomous, controlled by Druze militias which arose during the revolution against the Assad regime, which had also maintained independence from the main rebel formations. More on this below.

- Israeli occupation forces control the Golan Heights (occupied since 1967) and also an expanded region in Quneitra and Daraa provinces which they have seized since December, while also making incursions into Damascus province; Israel bars the government from moving its control south of Damascus under the threat of bombing, meaning government authority in Quneitra, Daraa and Suweida is incomplete at best.

- The heavily Alawite coastal provinces of Tartous and Latakia, as well as Alawite sections of Homs and Hama, are theoretically under government control, but there remain Assadist remnants in various parts engaged in a low-lying insurgency; meanwhile the Russian military still controls its major air and naval bases here.

- Parts of the northern border strip are still controlled by Turkish troops supporting their proxy Syrian National Army (SNA) militias; although theoretically dissolved into the new army, by all accounts they maintain significant independence.

- One third of Syria in the northeast is controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, backed by 2000 US troops.

- US troops also control part of the Jordanian border region in the southeast in collaboration with the Syrian Free Army (SFA, not Free Syrian Army-FSA), an ex-rebel brigade which fought only ISIS but not the regime, with US backing.

- In parts of the central desert region ISIS remains active. In mid-May, ISIS called on foreign fighters in Syria to defect to its ranks to join its fight against Syria’s government (accused of “idolatory” and “apostasy”), showing images of al-Sharaa shaking hands with Trump, followed by a May 18 attack on government forces in Deir Ezzor (previously most attacks were on the SDF).

The question of minority regions

Due to the way the government came to power, the new security forces which emerged are by default overwhelmingly Sunni in composition. The new General Security forces (GSS) and the new army consist almost entirely of cadre from former rebel groups. The GSS itself is virtually a proxy for former HTS cadre, and from the previous HTS-led Syrian Salvation Government of Idlib, and as such the government has been able to assert reasonable control over it. The new army, however, is simply a patching together of dozens of rebel groups who formally agreed to dissolve into it at the January conference, but many are not fully integrated, and there is limited command and control. There is no formal block on non-Sunni joining these forces, and this process has begun but is still in its infancy.

Clearly, unifying Syria is a crucial task for the new government, but the question is how this can be achieved, especially given this reality. This is connected to Syria’s religious and ethnic diversity. On the one hand, most of Syria’s Christians, Ismaelis and even Shia have maintained good relations with the new authorities, despite its Sunni-centric tendencies. It is where minority populations coincide with geographic regions that major issues exist: the Alawites on the coast, the Druze in Suweida in the south, and the Kurds in the northwest.

But there is a very important difference between these three groups: the Druze and the Kurds have been able to maintain security in their own regions, and pose a strong bargaining position with the government as they negotiate integrating into the national security architecture (despite agreeing in principle), because they developed their own armed forces during their autonomous struggles during the revolutionary period. By contrast, the only de facto Alawite armed forces had been those of the Assad regime; when it disappeared, they had nothing else, as Assad had repressed any sign of Alawite opposition.

The Alawite coast

This left a security vacuum in the Alawite-dominant provinces of Tartous and Latakia on the coast, and where they are a minority in western Homs and Hama. HTS attempted to fill this vacuum with the GSS, but the situation deteriorated. While both the GSS and local Alawite leaderships attempted to work together, on one side large numbers of armed Assadist remnants have hidden out in the region, with the support of a section of the population, while on the other, a section of the Sunni population – especially among those who lost everything, whose homes and entire cities have been destroyed – is bent on revenge for the genocide which Assad carried out against the Sunni population using Alawite fascist death squads (Shabiha) and armed forces overwhelmingly dominated by Alawite officers. Some killings targeted Assadist criminals, but this was combined with sectarian ‘revenge’ killings of Alawite civilians, as well as ordinary criminality in the security vacuum. This also coincided with a GSS push to arrest war criminals, which at times was carried out in a heavy-handed way with serious violations, and a growing Assadist insurgency beginning with the massacre of 14 GSS personnel on December 25 – quite a tragic cocktail of different elements.

The government passed thousands of former regime troops (mostly Alawites) through a process to ‘settle’ their status; once shown they had committed no crimes, they were free. However, the collapse of the Assadist repressive forces left these former troops without income, and no process began to recruit them to the new security forces, increasingly alienating them from the new authorities. While there was no formal block on recruitment of non-Sunnis, a certain reluctance with Alawites due to past Assadist affiliations combined with the government’s lack of money to pay new recruits due to the sanctions and catastrophic economic situation. This exacerbated the security vacuum, because, whatever the intentions even of the better GSS personnel, they were stretched thin, and without roots in the region and the Alawite community, they were in a weak position to confront the criminality.

On March 6, the Assadist insurgency broke out in full force in Tartous and Latakia, initially slaughtering over 120 of the new, young GSS members and 25 civilians. As the government scrambled to confront it, thousands of people poured in from around the country, including GSS forces, military factions from the new army, jihadi gangs, and armed civilian groups, enraged by the slaughter of the security forces and the audacity of remnants of the hated regime to attempt to return to power. Among these thousands were perhaps hundreds who, rather than help confront the Assadists, instead engaged in a horrific sectarian pogrom of the Alawite citizenry over the next two days, driven by a combination of sectarian hate (fomented by some hate-filled preaching), lust for revenge or simple criminality.

While some GSS units were reportedly involved in atrocities, overwhelmingly reports suggest this central arm of government, made up mostly of former HTS cadre, acted professionally, focused on fighting the insurgents, and took a heavy toll. Long time Syrian writer, activist and former political prisoner Yassin al-Haj Saleh claims, regarding the GSS, “in some cases, [they] exercised excessive repressive violence and captured Alawite civilians. … However, it was also the most disciplined, limiting further casualties in some instances, and it suffered significant losses in confrontations with armed Assad loyalists.” Even this report by an anti-Assad Alawite coastal resident, which is uncompromisingly gut-wrenching in its description of the mass murder and the terror of the Alawite citizens, nevertheless also speaks of the security forces “trained in Idlib” who were “known for their professionalism and respectful conduct toward the people of the Syrian coast,” and claims “the best of them” were massacred by the Assadist insurgents on the first day. The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) report does include violations by “General Security personnel” along with “military factions [and] armed local residents, both Syrian and foreign,” but assesses that the “vast majority” were carried out by certain of these “military factions” that only recently joined the new Syrian army. In Homs, the GSS formed cordons around areas to protect the Alawite citizens from armed gangs, while an Alawite woman interviewed on Gregory Alexander’s excellent Syria Revisited blog claimed “the General Security forces played a huge role in protecting the Alawite neighborhoods. This interviewee from the town of Qadmus – an Ismaili town surrounded by Alawite villages – reports no problems with the police or security forces (GSS), but with some of the “factions” (ie military factions), as well as the Assadists. Similarly, Latakia resident Alaa Awda recalled that “when general security entered for the first time, they were professional,” but when factions affiliated with the Ministry of Defense entered, “they were harsher, with executions, assaults and robberies.”

Saleh, like the SNHR and others, claims most atrocities were carried out by undisciplined military factions of the semi-integrated new army, above all two notorious SNA brigades “Amshat [the Sultan Suleiman Shah Brigade] and Hamzat” (both were widely named by other sources too) and by “jihadist groups, including foreign fighters,” and these forces “engaged in genocidal violence,” driven either by “malevolent ideological conviction” or “a mix of revenge, warlordism, and looting.” Notably, the Amshat and Hamzat brigades have long been under US sanctions for their extensive violations in Afrin when they took part in Turkey’s conquest of the Kurdish town, and they have now been placed under EU sanctions for their role in the coastal violence. These two brigades, plus another three notorious SNA brigades – Sultan Murad, Ahrar al-Sharqiya and Jaysh al-Islam – were also mentioned as violators in the report by the well-respected Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), as was a military brigade (Division 100) which was not SNA, but previously belonging to the now dissolved HTS. Irregular armed civilian groups, including from the region itself, bent on revenge, also played an important role in the atrocities.

On March 7, al-Sharaa demanded that “all forces that have joined the clash sites” immediately evacuate the region. The GSS managed to clear the region of the undisciplined forces, make a number of arrests and put an end to the slaughter by March 9-10, but according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, the toll included some 889 civilians or disarmed fighters killed by the forces nominally on the pro-government side, and 445 killed by the insurgent Assadist forces, including 214 members of security forces and 231 civilians.

On March 9, the government announced the appointment of an “independent investigation and identification committee, to look into the atrocities, consisting of seven people (including two Alawites), made up of five judges, a senior forensics officer and a human rights lawyer. The government’s investigation is due to release its report in several days, on July 10, and possibly its findings will make some of the above redundant.

During the crisis, al-Sharaa claimed that “many parties entered the Syrian coast and many violations occurred, it became an opportunity for revenge.” He continued that “We fought to defend the oppressed, and we won’t accept that any blood be shed unjustly, or goes without punishment or accountability. Even among those closest to us, or the most distant from us, there is no difference in this matter. Violating people’s sanctity, violating their religion, violating their money, this is a red line in Syria.” These are strong words. And the evidence from a range of sources above that that the state’s GSS was least involved in killing and was largely ‘professional’ and acted to quell the violence, likewise means that claims by enemies of the new Syria, as well as some sloppy journalism, that “the Syrian government carried out a massacre of Alawites,” are extremely irresponsible.

However, my aim here is not to make the case for government or GSS innocence, but simply that their roles need to be distinguished from that of the actual pogromists. It would be pure apologism to deny some level of overall responsibility: the military factions involved were undisciplined, yes, yet in theory they belong to the new army whose chain of command leads back to Damascus; while Sharaa’s own words were strong, some other government leaders tended to blame the Assadists for most crimes, or to downplay the massacres as “individual” violations; and as Syrian activist Rami Jarrah points out, while the Syrian government immediately declared condolences and mourning for the Christians killed in the late June ISIS church bombing in Damascus, there was no such mourning or even official condolences for the slaughtered Alawites.

Whatever the case, the future of the revolution – meaning beyond the mere ‘democratic space’ now open in Syria, the revolution’s promise of a Syria for all its communities, that rejects the methods of the past regime – now depends on how real, how effective, how transparent, how just this process of identifying, trying and punishing the perpetrators is, as well as working hard with Alawite community leaders for policies of compensation, reconciliation and inclusion in the institutions of the new Syria. Much depends not only on the report, but on the government’s response to it.

While some Alawites have declared their support for the government’s investigative commission, tens of thousands have fled Syria and countless more, likely the majority, will be too traumatised by these events to ever feel the new Syria is their home again. In the case of Hanadi Zahlout, a long-time Alawite supporter of the revolution since 2011, whose brothers were murdered, on the one hand she also gave her support to investigative commission, after Sharaa rung her and gave condolences, yet three months later, on the eve of the release of the commission’s report, she describes the situation grimly: “my home area is still surrounded by checkpoints. The killings continue and people live in constant fear, unable to resume their lives or even perform basic daily tasks like farming or moving along the roads. Families of the victims are still denied the dignity of burying their loved ones. Survivors continue to search in vain for healing. Homes lie in ruins, and children live in perpetual terror.”

Notably, leaders of ‘Amshat’ and ‘Hamzat’ still occupy important positions in the new army; if only street criminals but not ‘big fish’ are netted this will be farcical. Unfortunately, the injustice of seeing large-scale Assadist war criminals like Fadi Saqr walking the streets as reported above is not a good sign for justice for the Alawites – if leading Sunni criminals were to be brought to justice while leading Assadist criminals are not, it would lead to popular rejection and likely more sectarian ‘revenge’ violence. The worst outcome would be the government’s obsession with ‘social peace’ meaning neither set of criminals facing justice.

(The investigative report is due for release on July 10. This short section cannot do justice to the enormity of this issue; I will be releasing a big report on this to coincide with the release of that report).

The Druze south

While the Alawite issue was always going to be a minefield, the situation of the Druze is quite different; overwhelmingly the Druze opposed Assad, and the new stage of the revolution arguably opened with mass Druze demonstrations in September 2023. The various Druze militia – always independent of the rebel formations but also of Assad’s regime – played a direct role in the overthrow of Assad in December. However, they have resisted integration into the new army without certain guarantees.

In late April, a fake video purporting to show a Druze leader insulting the Prophet led to attacks on the Druze-majority town of Jaramana in Damascus by gangs of Sunni jihadists from the neighbouring area Mleha (“and other neighborhoods of Damascus heavily destroyed by the regime and Druze NDF members from Jaramana”). The defenders were government-aligned Druze security forces, who were reinforced by GSS forces sent in by the government to fight off the attackers. As these Druze civilians who were hiding out from the April 28 attack by armed jihadists reported, “Syrian security forces … had intervened to quell the fighting at the expense of suffering fatalities themselves” from the jihadi gangs. However, then four members of the government’s security forces were killed, and their bodies mistreated, by an anti-government Druze militia (including former pro-Assad Druze militiamen); in late February there had already been a clash in the same town between government forces and a Druze militia derived from the Assadist National Defence Forces (NDF).

After the government reached an agreement with the main Druze sheikhs in Jaramana on April 30, calling for accountability for those responsible for the clashes on both sides, two other Druze-majority towns nearby, Sahnaya and Ashrafieh, were also attacked by these outlaw jihadist groups, who created a lot of chaos leading to a number of casualties among both Druze civilians and GSS personnel. According to one local, these jihadists “stormed the city and started to shoot inside it” before clashing with “general security and groups from the Men of Dignity,” a powerful pro-revolution Druze faction that, while independent, tries to work with the government and GSS. However, at the same time, a different Druze militia, likely associated with the Suweida Military Council (SMC) which is led by former Assad regime generals, and which opposed engaging with the government, also reportedly killed a number of GSS personnel. Altogether up to 16 GSS were killed here, but reports make it unclear whether all or most were killed by Sunni jihadists or anti-government Druze fighters.

There were important divisions among the Druze leadership. “Top Druze clerics were split between calls for calm and escalation in response to this week’s violence. Two of the three Sheikhs of Reason, Yousef Jerboa and Hamoud al-Hanawi, issued a statement calling for calm and restraint on April 29. The third, Sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri, took an escalatory stance towards Damascus.” The Men of Dignity movement noted above, led by Layth al-Balous, is strongly identified with the first position. By contrast, the SMC identifies with Hijri’s anti-government stance.

These clashes left 48 Druze militia cadre, 28 government security forces and 14 civilians dead. Not good, but this outcome was vastly different from the disaster on the coast, partly because the attacking forces were much smaller, the GSS was more ready, it had not been preceded by a murderous Assadist coup, and above all because the Druze had their own armed forces. The government and most of the main Druze leaders – including Jerboa, al-Hanawi and al-Bahlous – reached an agreement that the GSS and police would be activated in Suweida, but they would be composed of local Druze; separatism was explicitly rejected, and Israel’s interference was rejected. Only Hijri, who had also expressed support for Israel, did not sign this agreement. The next day the government announced that over 1500 local faction fighters had applied to join the GSS; while the Druze militia themselves would remain the main military force for now, expectations were “underway to form a special military brigade for Sweida, affiliated with the Ministry of Defense.”

Israel launched a series of attacks on the region supposedly to “protect the Druze,” including an attack on Damascus close to the presidential palace, which Israeli leaders said was an warning to al-Sharaa. Netanyahu warned Israel would not allow the “extremist terrorist regime in Damascus” to harm the Druze. Some wounded Druze did flee to Israeli occupied parts of southern Syria to get hospital treatment for injuries. The Israeli Druze leadership, which supports the Israeli government and does not identify with the Palestinians, pressed for more Israeli intervention. The great majority of Druze reject Israel’s intervention and its pretence of “protecting” them, as well as any Israel-driven fantasies of a ‘Druze state’. As Syria watcher Charles Lister sums it up, “when Israel has militarily intervened, or threatened to do so, it’s only ever been to specifically protect Druze militias known for hostility to Syria’s new government and for having previously been part of, or loyal to Assad’s regime.”

Despite the sharp differences between the Alawite and Druze situations, one factor in common was the intervention of outlaw sectarian forces theoretically allied with the government, but with their own agendas. These rootless Sunni jihadi forces are causing mayhem, and the government needs to seriously rein them in, rather than only doing so when they begin killing. Some accuse the government itself of being behind them – they cause chaos, then the government sends in the GSS to restore order and thereby gain control of minority regions. Joseph Daher, a long-time anti-Assad Syrian analyst, believes sectarianism is promoted by the government as an ideology of state to cement its Sunni base; suppress class struggle, by diverting “the attention of the popular classes from social, economic and political issues by making a particular category (caste or ethnicity) a scapegoat as a cause for the country’s problems;” and to be used as a tool of repression when necessary, for example, he claims that strikes against anti-worker policies have declined since March due to fear the sectarian gangs may be used against them – while there has been no evidence of any such use, it is a legitimate concern.

The former HTS base is a spectrum and therefore linkages no doubt exist at some level between sections of the state machine and such jihadist gangs; it is not unusual for bourgeois governments to use sectarian, nationalist or similar prejudices to homogenise and mobilise their base in a way that heads of united working class struggle, so Daher’s analysis may partially explain these phenomena. However, this seems too conspiratorial a reading to fully explain either the far more complex events, or the actions of a government under pressure from a variety of directions, many of which are in contradiction to the priorities of its former jihadist base. For example, on the coast, the government obviously did not organise an Assadist insurgency and slaughter of their own forces in order to then have to fight to regain control; in Suweida, the GSS lost lives to the jihadis from the first day, and the outcome in the final agreement would appear positive for the Druze. Arguably the actions of sectarian jihadists are deeply destabilising for a government attempting to hold the country together and help it recover. Not having the resources to properly control the base (whether in uniform or not) is just as plausible an explanation than a deliberate strategy in my view, but many aspects probably combine to make the big picture.

[The big clashes between local Druze and Bedouin fighters which erupted in mid-July, bringing the government security forces in to quell the fighting and sign a new agreement with the Druze leaderships, which then collapsed, leading to far greater violations than in this episode, indeed, a horrific massacre, and involving large-scale Israeli airstrikes on government forces and on Damascus, occurred too late for this piece, and would require substantial new analysis].

The localised security outcome for the Druze [which was confirmed following the rivers of blood shed in July] needs to be repeated with the much more difficult Alawite situation: it is an urgent task for the new Syrian police, security forces and army to recruit former Alawite equivalents whose status has been settled, not simply to provide them with income but to end the security vacuum in their regions and as a step to fuller inclusion of the now effectively excluded Alawite part of the population.

The Kurdish northeast

The Kurdish situation is extremely complex. Turkey immediately took advantage of the overthrow of Assad to push an attack on some regions held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which included bloody attacks on Kurdish civilians; indeed, the SNA was not really involved in the HTS-led offensive which toppled Assad, but rather in this side venture. However, the situation is far from straightforward and not everything can be reduced to a simplistic “Turkey and/or Syrian government versus the Kurds” narrative.

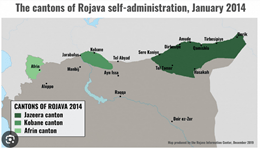

The shape and size of the region controlled by the SDF, called ‘Rojava’ or the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), covering 30 percent of Syria (Hasakah, Deir Ezzor and Raqqa provinces), has little correspondence to the regions with majority ethnic Kurdish composition. The three Kurdish ‘cantons’ controlled by the Peoples Defence Units (YPG) from 2012 onwards corresponded quite closely to Kurdish populations; like the Druze militia, they tended to be independent of both the regime and the rebels, though at times they cooperated with one or the other. The great expansion of SDF control began after 2014 when the US airforce intervened to save Kurdish Kobani from the genocidal ISIS assault, and from then fought alongside the SDF to liberate the rest of the territory controlled by ISIS over the next 4-5 years – most of which however was Arabic in composition. Of course, given the options in east Syria being SDF, ISIS or the Assad regime, these Arab populations preferred SDF hands-down, but it is not clear that remains the case now that regime has fallen.

Therefore there are two related but distinct questions: the future of AANES as a separate statelet with its own armed forces, and its own political system, from the rest of Syria; and that of the national rights and autonomy of the actual Kurdish regions.

In December, several days after the revolution, a popular uprising of the Arab population took place in Deir Ezzor city against SDF rule; they wanted to join the new main Syrian polity, and the SDF wisely let go. However, nearby in also Arab-majority Raqqa city, the SDF is alleged to have used violence against a similar movement.

The initial Turkish-SNA offensive against the AANES in December only reconquered the Arab-majority regions of Tel Rifaat north of Aleppo, and Manbij on the northern border. The SDF had taken Manbij from ISIS in 2016, aided by the US airforce; Tel Tifaat, however is a different story – the SDF conquered that Arab-majority region from the democratic Syrian rebels in January 2016 with the aid of the Russian airforce intervening to back the regime. Arguably, therefore, regardless of Turkish means and motivations, in neither case was it necessarily ‘wrong’ or anti-Kurdish that the SDF lost them. However, two caveats. Two years after the SDF conquest of Tel Rifaat, Turkey and the SNA conquered Kurdish Afrin, also in the northwest, and much of the Kurdish population fled to the Tel Rifaat region, from where a similar number of Arabs had earlier been expelled; as such, it was these uprooted Kurds again on the move. Secondly, while Manbij itself is majority Arab, it is dangerously close to Kurdish Kobani. From that point conflict stalemated around the Tishreen dam on the Euphrates river which separates their forces.

From the start, the new HTS-led government stressed a negotiated settlement with AANES, implicitly rejecting the Turkish approach. Syrian defence minister Abu Qasra called for the formation of a united military via negotiations with the SDF that would serve “as a symbol of the nation rather than a tool of repression.” Foreign minister Shaibani issued a Kurdish-language statement on January 21 declaring “The Kurds in Syria add beauty and brilliance to the diversity of the Syrian people. The Kurdish community in Syria has suffered injustice at the hands of the Assad regime. We will work together to build a country where everyone feels equality and justice.” Senior SDF official Ilham Ahmed responded that Shaibani’s remarks were a “place of honour for the Kurds. The Kurds will bring their own colour to Syrian society when their rights are guaranteed in the constitution. We will build together a new Syria that is diverse, inclusive, and decentralized.”

Following several meetings between al-Sharaa and SDF leader Mazloum Abdi (the former had also welcomed Abdi in the Kurdish language), the two leaders signed a joint declaration on March 10 to integrate their administrative and military institutions over a period of time negotiating the details. The agreement included a nationwide ceasefire, return of displaced civilians, guarantees for political representation across all ethnic and religious groups, and for the first time in Syrian history, the Kurdish community is explicitly acknowledged as an indigenous component of Syria, with constitutional guarantees for citizenship, linguistic rights, and cultural recognition.

This was a tremendous step forward, the polar opposite of the catastrophe on the coast just winding down at the time; how it develops is crucial for the future of a democratic Syria. A few days later, the SDF rejected the interim constitution because it did not reflect the spirit of the agreement days earlier; and in particular, Arabic remains the sole official language. There are important differences to be ironed out; the SDF wants to integrate into the Syrian army as a bloc, while the Syrian government wants a unified structure with no blocs. This is related to the SDF’s preference for a federal system, with wide-ranging powers for regions with ethnic, religious and cultural minorities, which is rejected by the government.

Arguably, ‘federalism’ (depending on the definition) does not work in Syria’s reality, where most ‘minorities’ are religious rather than ethnic, and would thus entrench sectarian identities as in Lebanon; and even with the ethnic Kurdish minority, there are few regions that are not to some extent ethnically mixed. While some non-Kurdish (Arab, Syriac) peoples in parts of AANES (especially in Hassakeh province) appear to be supportive of the Rojava arrangement – which is officially multi-ethnic rather than Kurdish – others appear not to be (especially in Deir Ezzor and Raqqa); according to one source, “the overwhelming majority of Arabs living in the autonomous region express support for immediate integration into the new Syrian state. But this only underlines how difficult it is to find a clear solution, and the problem of what criteria would define ‘federal’ units, if not based on clear ethno-national criteria.

However, some degree of decentralisation where the administrative and security apparatuses are strongly representative of the diverse populations of regions such as the northeast, the coast and the south seems essential to forging a new Syrian unity given Syria’s reality. In practice the first major step taken under the government-SDF accord process was very promising: an April agreement for the SDF to move its military forces out of two Kurdish districts of Aleppo city, while leaving their internal security forces there, which will be supplemented by the government’s General Security working in collaboration, and the Kurds running their own administration, schools and the like. Such processes, along with the outcome for the Druze outlined above, offer hope, and with some will, could be extended to other Kurdish regions; the critical leg of this process will be how this works for the Alawites.

Unfortunately, the latest meeting between Sharaa and Abdi in July was inconclusive, with the government apparently unresponsive on decentralising initiatives, and the SDF insisting on a federal arrangement whereby the whole SDF enters the Syrian army as a bloc, even insisting on keeping Deir Ezzor and Raqqa within such a federal unit. According to one report, Shaibani asked the SDF to withdraw from Arab-majority Deir ez-Zor, but the SDF responded that was a matter for joint committees to discuss. While arguably the SDF position is maximalist, the government’s own insistence on a centralised state is arguably likewise; and seems to contradict its own agreements with the Kurds in Aleppo and the Druze in the south. Especially after the Alawite massacres, no minority will give up some kind of security control and simply trust a ‘centralised’, Sunni-dominated arrangement.

While the SDF joining the Syrian army as a ‘bloc’ may seem unreasonable, it may also be a bargaining chip. For instance, does the government’s position mean that MOD decides where any troops are stationed? Does it mean a central decision could be made, for example, to send former SNA troops into Kurdish regions while sending Kurdish troops to, say, Daraa, a decision that could have disastrous consequences? Or does it simply mean that some new divisions of the Syrian army could be established in the northeast, to mostly incorporate former SDF troops? One article suggested the government would accept the Kurds running their own councils and internal security, just not a separate army. But it remains unclear exactly what was proposed by each side. Clearly, some kind of middle ground needs to be found.

It is also not straightforward for AANES to simply dissolve the entirety of its political-administrative structure into the transition Syrian polity; whatever one views as the positives and negatives of each, both have arisen via a degree of popular negotiation in revolutionary conditions, and only a sustained negotiation process involving the people on both sides, and not only the leaderships, can bring about a real unity which has popular legitimacy. Any attempt to force the situation will only result in bloodshed and the return of massive instability.

This necessity to forge a real Syrian unity should not be viewed as a ‘compromise’ with ‘separatism’, but rather is essential to standing against not only internal sectarian or separatist threats, but also external (especially Israeli or Iranian, but potentially Russian, Turkish, UAE or US) exploitation of these divides; it is a life and death question of the revolution’s security, given the number of real and potential foreign enemies it has. This will be discussed in Part II of this series, New Syria’s Foreign Policy.

Where to from here?

Given the current stage of post-revolution Syria – a democratic revolution with a bourgeois-Islamist leadership with mildly authoritarian tendencies in a catastrophic socio-economic situation – what should those advocating a more radical-democratic or socialist orientation advocate at this time? Here are a number of important issues, by no means intended as exhaustive.

- First, demanding the complete, comprehensive end of sanctions on Syria. Fortunately, this step is now in progress (which it wasn’t when this piece was started), but the process is not complete, and various US leaders continue to imply that it may be conditioned on certain geopolitical moves by the government (see Part II of this series). Indeed Trump recently threatened that “The Secretary of State will reimpose sanctions on Syria if it’s determined that the conditions for lifting them are no longer met.” All unacceptable conditions must be rejected and sanctions lifted unconditionally. The economic strangulation of the Syrian people must end, so that the government has the money to pay proper wages for public services (including security), industry begins to move and creates jobs, and housing, energy and infrastructure can be repaired.

- However, this renewal of local and foreign capitalist investment needs to take place under the supervision of workers’ committees and the broader community to limit corruption, protect workers’ rights, and attempt to ensure the benefits accrue to society rather than just the capitalists. And while this capitalist investment is essential, sweeping privatisation should be rejected as far as possible. An economic orientation towards restoring the health of state coffers so that it can expand its own investment in key sectors should be supported. Mass retrenchments should be rejected, and if there are legitimate issues of fake jobs created by the old regime, this should be dealt with under workers’ supervision. The proposed 400 percent wage increases should be available to all public sector workers to set a standard for workers throughout Syria.

- Reactivation of civil society and push for more democratisation against centralising tendencies – the great range of local coordinating committees and people’s councils that arose during the revolution, and were crushed by the regime, provide a terrific blueprint for what is possible, once sanctions relief hopefully leads to people being able to look beyond the everyday struggle for survival. Support all popular initiatives to protect the current democratic space and utilise it to push people’s demands. This in particular applies to women’s organisations mobilising to obstruct any attempts to impose “Islamist” restrictions on their democratic rights. In various places, new councils have begun to be formed after free elections, for example the Al-Ahli Musyaf Council following elections in May. At a higher level a genuine national dialogue conference might be pushed for, and discussion of the new constitution needs to be an open, democratic process.

- A transparent process of transitional justice needs to get underway. If ‘truth-telling’ needs to come first then it also needs to get underway. If no-one is held accountable for years and decades of Assadist crimes against humanity, and major Assadist criminals walk free while others grab sections of the economy, the result will not be social peace but quite the opposite. Transitional justice also includes crimes carried out by non-Assadist forces, including in the past by HTS and its predecessor Nusra, relatively minor as they may be by comparison. But only if Assadist crimes are appropriately punished will many among the Sunni majority accept the necessary punishment which must be given to Sunni sectarians who engaged in the Alawite massacre in March. Meanwhile, on June 6, the Supreme Fatwa Council issued a fatwa declaring that those who have been wronged are “obligated to obtain their rights through the judiciary and competent authorities, and not through individual action,” declaring acts of “revenge or retaliation” to be forbidden – a healthy step.

- The government needs to crack down on uncontrolled armed jihadi groups, of the type that took part in the Alawite massacre and led the attack on the Druze in southern Damascus. This will be no easy task – their existence is related to a number of factors: first, the lack of transitional justice; second, the lack of jobs in Syria’s current catastrophe (in this sense they have something in common with their Alawite enemies who took part in the Assadist insurgency in March), and so economic improvement is just as important as transitional justice; finally, the fact that many of them belong to the traditional jihadi base of HTS from which the current leadership arose, so despite the instability they cause being damaging to the government, there may be elements within the ruling state apparatus that still have connections to these groups, especially at base level, and there may be times the government surreptitiously uses their sectarian antics to its benefit. It is essential that the government acts to prevent their deeply destabilising impact.

- But as members of the new army also committed massive violations in March, the government also needs to establish control over wayward military factions; an important step took place on May 30 when the Ministry of Defense issued a code of conduct and discipline for the army, which demands troops “treat[ing] citizens with dignity and respect, without discrimination based on religion, race, colour or affiliation,” observe human rights standards, protect civilians and so on, and prohibits any assaults on civilians or property, “engaging in any form of discrimination,” “proclaiming slogans or positions that undermine national unity or disturb civil peace” and so on. A great start, but making this reality remains a challenge [update: a challenge which completely failed in Suweida in July].

- Related to this is the necessity of a political struggle against sectarianism. It is one thing when ‘street justice’ in the absence of court justice targets actual criminals; it is an entirely different thing when the entire Alawite population is associated with the crimes of the Assad regime and targeted collectively (and even more when this is extended to other non-Sunni minorities that had no connection to the Assad regime, such as the Druze). While obviously the Assad regime’s criminal weaponisation of sectarianism to carry out its counterrevolutionary war is responsible for this mutual hate, liberation means not simply reversing the victim but fighting the ideology.