By Michael Karadjis

Today, November 27, marks one year since the sudden Syrian rebel offensive landed them in control of Aleppo in 3 days, and in Damascus in 10 days, with the complete collapse like a house of cards of the 54-year hereditary monarchy of the Assad family. Everywhere they marched, the hated tyranny collapsed; no Syrian soldier considered it worth risking their lives for. Thousands of people gathered everywhere they arrived, stunned at the very idea that that the totalitarian nightmare that had caged their lives for as long as they had known had suddenly vanished into history. (I wrote this around a year ago).

The prison doors were flung open everywhere, especially Sednaya, the empire of evil, the capital of the Assad family’s Torture & Disappearance Inc. Thousands were released, even more stunned that their torturer was suddenly gone and they could breathe the air of freedom, could walk out and curse without being killed or jailed again. Many had lost their minds, did not know their names. Many had been there for decades. A 55-year old man saw the light after 39 years, jailed at 16 when a student from Lebanon for joining a party. Raghid Ahmed Al-Tatari, the pilot ordered to bomb the rebellious city of Hama in 1982 and refused, jailed for this heroic disobedience, saw the light of day after 42 years. Palestinian man Bashar Saleh had tried to shake the hand of Ahmad Jibril, a ‘Palestinian’ traitor who led the misnamed ‘Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command’ (not to be confused with the actual PFLP), an organ of Baathist regime intelligence – but did so from his seat rather than standing up – so had been thrown into Sednaya for this slight 39 years earlier – and was now released. Some 600 Palestinians were also released, including 67 Hamas cadre, but 1300 Palestinians had been tortured to death in captivity, including 94 Hamas cadre, on top of some 7000 ‘disappeared’.

But the release of mere thousands – perhaps 25,000 – was a huge disappointment. Because at least 130,000 were known to have disappeared. The releases left over 100,000 unaccounted for – ‘disappeared’ by the regime, after it finished torturing them, into mass graves scattered around the country. The since updated database of the Syrian Network for Human Rights now puts the figure at 177,057 people forcibly disappeared. To be clear, this is on top of the 600-700,000 killed in the regime’s counterrevolutionary war itself, during which it destroyed entire cities and entire chunks of the country, in many places leaving no homes standing at all, a Gaza-like moonscape over much of Syria.

Why November 27? Addressing false discourses

To step back, why November 27? The name of the offensive – ‘Operation Deterring Aggression’ – demonstrates how little clue the rebels had when they began that the regime would collapse in 10 days. They thought they were, literally, deterring the regime’s aggression. A shaky ceasefire between the regime and the last remaining pockets run by anti-regime militia in the north, especially in Idlib, had been signed in 2020, under Russian-Turkish-Iranian auspices. But from the time that Israel began its genocide in Gaza after October 7, 2023, the regime and Russian airforce turned in the opposite direction and began attacking and bombing Idlib. The rebels therefore began planning an offensive to “deter” this regime “aggression.” However, there was a problem. Throughout these years, the fascist regime had been backed not only by Russia, but also by Iran, Iran-backed Shiite militia from Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and by Hezbollah. At this moment, however, Hezbollah was taking a break from killing Syrians, and had returned to its original resistance credentials by firing across the northern Israeli border in solidarity with Gaza.

Now, the Syrian people, including the rebels, hated Hezbollah. If you can’t understand that, you probably need to do a little more research and expand your horizons beyond binary thinking. If Hezbollah had been dragged kicking and screaming into Syria by its Iranian masters and simply held up the rear, that would have been one thing. Instead, they took a lead role in a number of IDF-style regime starvation sieges around Damascus, during which hundreds actually starved to death, and these entire Sunni towns were uprooted and the people expelled to the north. So just let that sink in. But right then, Hezbollah was preoccupied with Israel. But, despite the inconceivably inaccurate popular understanding of this, this was precisely a problem for the rebels, not an “opportunity.” Because much as they hated Hezbollah (and Iran), they also hated Israel. The entire October 7 2023 to December 27, 2024 period, the rebels in Idlib and northern Aleppo organised rallies, seminars, fund-raisers in support of Gaza – the only part of Syria where this happened. One campaign raised $350,000 for Gaza, a remarkable achievement for a poor rural province under Assadist siege; April 2024 saw the opening of ‘Gaza Square’ in Idlib. Meanwhile, the Assad regime banned rallies in support of Gaza or Palestine, and in contrast to other alleged “axis of resistance” components, did not lift a finger on the Golan, even symbolically, to support Gaza, but also did not even lift a finger to support Hezbollah, in its existential hour of need (and neither did Iran btw), in fact the regime closed Hezbollah recruitment offices – despite all the honour Hezbollah had lost saving his regimes arse – and even engaged in intelligence cooperation with Israel against its erstwhile Iranian “allies” who Israel was bombing inside Syria!

Therefore, the rebels waited until November 27 because that was the day the Israel-Hezbollah ceasefire was signed, in which Hezbollah agreed to move north of the Litani River, away from the Israeli border. They did not move to deter the aggression against themselves until they could be sure they were not helping Israel in doing so. Despite the sensational ignorance and privilege of much of the western ‘left’ who think the rebels moved at that point to help Israel, surely a little common sense would tell them that if this were the aim, they would have moved during the height of Israel’s attack on Hezbollah, not wait till it was over. Countless thousands of Iran-backed militia were still in Syria, who could have tried to save Assad if they had chosen to. They did not fire a shot, and on December 6 made an agreement with HTS to facilitate their total and peaceful exit from Syria (I have discussed these issues here).

Israel’s one full year of aggression beginning on December 8

From the morning of December 8, when the Assad regime collapsed and Assad and other criminals fled to Russia (while some of the criminals fled to the UAE or Iraq), Israel began its biggest air war to date, weeks of bombing and destroying Syria’s entire military arsenal, all the advanced weaponry that Israel never touched as long as it was under the control of its preferred Assad regime. Israeli leaders from Netanyahu down claimed the new Syrian government was a “terrorist organisation that has taken over a state,” the IDF occupied a swathe of territory in southern Syria beyond the already occupied Golan Heights (Israel and Assad had both respected the 1974 UN disengagement lines for 50 years, which left Israel in control of the Golan but without Syrian or global recognition), and Israel has continued to launch air attacks of varying intensity, and less visible ground attacks in Quneitra and Daraa – seizing farmland, raiding houses, arresting civilians and taking them to Israel, taking control of water supplies etc etc – ever since; there has been no let-up, only less media (I wrote about this Israeli aggression here).

Just one example of the ongoing, daily nature of Israeli aggression: on November 28, as if to demonstrate their hostility to the Syrian revolution anniversary, Israeli troops and tanks raided the town of Beit Jinn, southwest of Damascus, attempting to seize a number of residents – as they regularly do. When locals resisted, six occupation troops were allegedly wounded, so the invaders brought in the airforce and attacked the village with shells, drones and artillery, killing thirteen Syrians. The Israeli military claimed “armed terrorists” fired on their troops, who responded “along with aerial assistance” and “a number of terrorists were eliminated” – as elsewhere, Israel believes it is its occupation forces who have the right to “self-defence” against locals resisting their invasion. Israel claimed they to be arresting cadre from Jama’a Islamiya, a Lebanese Sunni Islamist group which fought with Hezbollah against Israel, but also supported the anti-Assad revolution in Syria, but Israel regularly makes claims it produces no evidence for. The Syrian foreign ministry vigorously condemned the “full-fledged war crime” and “horrific massacre” carried out by the occupation army, claiming this “is a systematic policy by the Israeli occupation to destabilize the situation in Syria and impose an aggressive reality by force.”

Meanwhile, Russia still has its air and naval bases on the coast, the US still has a (reduced) military presence in the northeast, and Turkish forces are still present in parts of the north.

Assessing one year of post-Assad Syria

How can we assess one year of post-Assad Syria? That of course is a question beyond the scope of this mere ‘anniversary’ essay. I wrote a detailed sum-up of the first six months in domestic post-Assad Syria policy here; though that was before the Suweida massacre in July, which I thus wrote about here. The first article did cover the coastal massacre in March, however, but I also wrote a much more detailed report on that here. I’m about to release a thorough report on the foreign relations of the new Syria the next few days.

There are a number of points we need to consider together.

First, the new government inherited ruins. The World Bank estimates the minimum cost of reconstruction to be 215 billion $US; many estimates are several times that amount. Millions of homes, thousands of schools, hospitals, markets, every kind of basic facility, need rebuilding; two and a half million children are now out of school. Syria is the fourth most food-insecure nation on Earth. There is no real economy; there are few jobs. The job of the Assad regime was to destroy its country, and as long as Russia and Iran were willing to keep pouring in money and guns to keep their favoured mafiosi in power, it didn’t matter. Fourteen million people – 60 percent of Syrians – were uprooted, half internally displaced within Syria, and the other half, nearly 7 million people, as refugees abroad, the world’s largest refugee population. Perhaps 2 million internally displaced and one million refugees have returned. For many, returning to no home, no job, no money, no economy, and little security, is not on their agenda right now, for these obvious reasons. Therefore, the job of a new government inheriting the ruins created by a previous one is to reconstruct the country and get the economy moving – that is its primary brief, and its actions must be seen through that primary lens.

Second, this desperately poor and destroyed country is under permanent Israeli aggression and occupation, and US sanctions which had been imposed on the previous regime yet, absurdly, continued after that regime vanished. There is no global socialist fund to help countries reconstruct – most reconstruction funds will come from foreign investment, aid and loans, with all the strings attached. But as long as sanctions continue, and the threat of ‘snap-back’ exists when they are merely ‘suspended’, very little reconstruction money will enter Syria. From December to May, the US took a somewhat hostile stance, and then approached Syria with a list of draconian ‘conditions’ for mere sanctions ‘relief’. Trump’s sharp turnaround in May – during his Gulf extravaganza, at the behest of his Saudi and Qatari hosts and the Erdogan regime in Turkey, who all want to invest and make money in Syria – when he declared that “all” sanctions would be lifted “immediately” – thus appeared a big victory over this edifice of humiliating “conditions” being erected by the White House, State Department and National Security Council. In doing so, Trump went against not only many of the MAGA Islamophobes and “anti-terrorism” tsars, but also against Israel, which had appealed to Trump to not lift sanctions. This resulted in some announcements of some large investment projects, especially in crucial energy infrastructure, from Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, France and China. However, the reality is that Trump’s statement had little meaning – the sanctions may still be lifted by the end of the year (with snap-back provisions) but to date they still exist and hold up any real recovery (I wrote about the sanctions lifting issue here).

Meanwhile, as long as Israel continues with its unprovoked war of aggression and occupation in the south, this is all the more reason for investors to not invest – who wants to invest in a war zone? And this is partially Israel’s very goal – Israel openly says it wants to keep Syria poor, weak, divided, it wants Syria’s current serious divisions widened, for the country to break apart, and for the government to collapse.

Third, because Assad had already meticulously destroyed every other Syrian rebel force, had crushed the civil uprising, destroyed entire cities where hundreds of revolutionary councils had ruled in the early years of the revolution, expelled entire populations from the south to the north, expelled millions from the country, it so happened that the only significant rebel force left standing, partly due to Turkish protection, but also due to Assad’s focus on crushing democratic revolution, was the Islamist militia HTS, then ruling over Idlib in the northwest. Some other rebel groups also ruled other parts of the north, but they were even more co-opted by the Turkish government; HTS, with all its faults, was at least independent. HTS had attacked and crushed many other rebel forces over the years, and had assassinated some prominent revolutionary leaders. For most Syrian revolutionaries in the spirit of 2011, it was the last quasi-rebel force anyone wanted to come out on top. But given Assad’s crushing of everyone else, the Assad regime’s complete collapse allowing HTS-led forces to walk in, and a degree of transformation of HTS itself (it remained a rightwing Islamist group, but those ‘leftists’ calling it “al-Qaeda terrorists” are best described as the ‘Neocon left’), history simply brought this about.

But what does that mean? The government, to state an obvious truism, is a capitalist government; no-one was expecting socialist revolution. Its economic orientation is neoliberal; in fact, given the money in the hands of former Assad cronies, some of these have already been partially rehabilitated in the economic field; meanwhile, large numbers of workers have been retrenched from the public sector. And while HTS dissolved in January, the most important government ministries are led by former HTS members. However, the circle has broadened considerably beyond the former HTS since then. The cabinet of 23 only has four ex-HTS members, and another 5 with some association with it; includes mostly technocrats; but there is only one woman, one Christian (the same as the one woman, who however was a prominent democratic activist), one Alawite, one Druze and one Kurd, its attempt at ‘diversity’ thus looking highly tokenistic. It is not a government I would be supporting, but it is not about me; one way or another, it appears to have the strong support, at present, of the majority of the Syrian population, or at least of the majority, Sunni Arab, population; it has legitimacy.

The government has promised democratic elections in several years, once the conditions are more suitable (at present elections would exclude millions uprooted and in exile, there has been no census etc); in the meantime, it held a kind of farcical semi-election which did, however, involve a degree of popular input, for a transitional peoples assembly – this did further widen the governing body, but still the number of women and minorities ‘selected’ was far lower than the government’s own projections. Of 119 ‘elected’, only 6 were women, and 17 minorities (4 Alawites, 4 Kurds, 4 Turkmen, 3 Ismailis & 2 Christians). No Druze were selected because Suweida is temporarily outside Syrian government control, and likewise the ‘election’ did not take place in Raqqa or Hasakeh under SDF control, thus excluding most Kurds, but seats have been left vacant for these three governates; but all three seats in Afrin were won by Kurds. On the other hand, it is notable that no seat was won any former HTS cadre. One aspect widely considered the most negative about the process is that another third of seats are to be directly chosen by the president, giving Sharaa a huge amount of power; however, one expectation is that the president’s choices should be aimed at fixing up any imbalances. Whether Sharaa appoints significant numbers of women and minorities is therefore an important test, and if he does, it will be a somewhat ironic outcome from a democratic perspective.

The other side of the equation is that the post-Assad polity contains a democratic space that the Syrian people have never experienced before. This is the major gain of the revolution, the major contrast to the past; this is what must be preserved, against attempts by domestic and foreign enemies, or the government itself, to crack down on these democratic rights; and this is what must be greatly expanded. Sednaya and the entire edifice of Assad’s torture gulag are gone; they have not re-opened. People can demonstrate, hold rallies and meetings, criticise the government, without fear of persecution, let alone fear of being gunned down by guns and tanks, bombed by barrel bombs and chemical weapons, or jailed, tortured and disappeared. Women have demonstrated against government ministers suggesting outrageous things; far from forcing women to cover up as was warned of, even the only woman in the Syrian cabinet does not wear hair covering. There have been workers’ strikes, but without real jobs, without reconstruction, without a revival of industry, there can be no working-class movement with any strength – and when we speak of ‘neoliberalsm’, essentially this means capitalism today – it is only through workers’ rights to organise that this can be confronted, not through illusions in ‘better’ government policy if another party were running the country.

Sectarian divisions in new Syria: inheritance of Assad regime’s genocidal sectarian war

Both of these truisms – ‘capitalist government’ and ‘democratic space’ – must be set in the context of what has already been stressed – that of a destroyed country. But it is not only the physical destruction. The Assad regime destroyed Syria’s social fabric to a sensational extent, something not commonly understood. The two rounds of sectarian massacres – of Alawites in March and Druze in July – are such a stain on post-Assad Syria that it would be easy here to simply say that the new regime is just a Sunni Islamist version of the Alawite-dominated Assad regime. Following the murder of hundreds of Alawite and Druze civilians, even if these two communities hated the Assad regime (the Druze rose against the regime, while even many Alawites hated a regime which spoke in their name but robbed them daily while killing off their young men as cannon fodder), they would now see their lives as worse in the new situation. Indeed, much as I am against all foreign intervention in Syria, I would frankly not be opposed to some temporary UN protective role on both the coast and in Suweida, as these people are essentially victims of the consequences of the Assad regime.

However, just because it would be ‘easy’ to make such a simplistic statement – that the Sharaa government is just a Sunni Islamist version of the Assad regime – does not make it correct. We still need to reckon with the fact that for the vast majority of Syrians, the situation is infinitely better. Can the Druze now blame themselves for being in the forefront of the overthrow of Assad? Can the Alawites now blame themselves for standing aside as the regime collapsed and welcoming the rebels? If HTS had planned a sectarian massacre, would we not have seen signs of it then? In reality, one of the aspects of the revolution that was so positive was precisely the lack of sectarian ‘revenge’ and the clear and open calls by the new leadership to avoid it. The regime collapsed because it was rotten to the core; nothing could have saved it.

But the inheritance of the Assad regime’s counterrevolutionary sectarian war was a country deeply divided. Hundreds of Alawites were killed by Sunni sectarians in March; hundreds of Druze were killed by Sunni sectarians in July; tens of thousands of Sunni civilians were slaughtered in sectarian massacres by Assad’s fascistic ‘Shabia’ thugs throughout Syria in 2012, 2013 and 2014 in particular in countless large and small sectarian massacres. This cannot be overestimated, and cannot be brushed aside as Assad using repression against “everyone against him.” He did, but this was in addition to the specifically sectarian component of his war. I wrote in detail about Assad’s regime being “the incubator of sectarian mayhem” in one section of my large article on the coastal massacre. In addition, the towns and parts of cities destroyed were Sunni; the millions of homes destroyed were Sunni; the starvation sieges were against Sunni towns; most of the displaced internally and externally are Sunni; the 2 million living in tents in the north are Sunni. It is not “sectarian” to tell the truth, to analyse (it IS sectarian for elements of the current government or its supporters to exploit this to make everything about “Sunni victimhood” in order to justify their own sectarianism – but the point is this DOES have a basis in reality).

All of this had consequences. When the Assad regime vanished, and its leading thugs ran chicken to Moscow or Abu Dhabi, the regime armed forces and security forces collapsed; it could no more continue existing than the Nazi death squads in 1945. While both the Druze and the Kurds had their own armed forces (which allowed the Druze to beat back government-backed militia in July), independent of both the Assad regime but also of the main rebel groups, the Alawites had only had Assad’s armed forces – every other sign of independent Alawite life had been crushed by the Assad regime. Meanwhile, the overwhelming majority of the rebel armed forces by then de facto consisted of Sunni – yes some occasional Christians or even other smaller minorities also, but overwhelmingly Sunni. The ‘new army’ patched together in January through the dissolution of the rebel militia was thus a de facto Sunni armed force. New internal security forces (the GSS) were set up, largely from people associated with the Idlib statelet. Negotiations with the Druze (until July) and the Kurds and SDF/AANES (ongoing) to integrate their armed forces into the new army will hopefully yield results, but have not yet.

But the Alawite question festered. The Alawites who lost their jobs in army, police and security forces had no work; and there had been little time – or apparent intention by the new authorities – to begin integrating them into the new armed and security forces. Meanwhile, these Alawites (and Sunni members of Assad’s forces) passed through ‘resettlement’ centres to settle their status, to prove their innocence – but though ‘resettled’, they could still find no work. But meanwhile, thousands of Sunni Syrians, uprooted, returning to destroyed or occupied homes, could likewise find no work, because none existed. And while former Alawite soldiers were rightly ‘resettled’, these Sunni and other victims of the Assad regime received no justice because, despite arrests, not a single butcher, torturer, criminal from the old regime has yet been put on trial; lack of transitional justice allows irrational resentments to fester.

It is notable that the US sanctions – in denying the beginnings of economic recovery and reconstruction – played a role in both the drift of some of the cut-loose Alawite population towards the growing Assadist insurgency, and of the phenomenon of armed, rootless sectarian Sunni rabble – no jobs, no income, no hope, no justice, allows the sectarian inheritance of the former regime to fester on all sides. Some observers, such as Syrian activist Joseph Daher, argue that the new regime is weaponising Sunni sectarianism to build its power base in much the same way that the Assad regime was dominated by the Alawite minority; others emphasise the inability of the young government to effectively control the Sunni dominated armed forces and still less armed sectarian Sunni elements among the population; I believe the jury is still out in this question and the answer is far from simple.

Sectarian massacres of Alawites and Druze: Sections of the population lost by the people’s revolution

Into this explosive mix came the murderous March 6 uprising of former Assadist officers who had been hiding out, with tons of weapons, in the coastal mountains. They ambushed the new security forces – mostly new, young men just recruited – and murdered hundreds of them, alongside some 200 Sunni civilians, and seized government buildings throughout the coast. The government sent in more security forces, and the new army, to crush the coup – as was its responsibility. Thousands more troops and armed civilians also poured in at that chaotic moment, horrified at the prospect of the genocidal regime returning and at the hide of them even showing their faces so soon, and to avenge the murdered new, young security officers, while some mosques and social media sites pumped out sectarian hate. While most may have stuck to script, hundreds did not, and instead invaded Alawite villages and small towns and took irrational ‘revenge’ by slaughering the Alawite citizenry, destroying and looting. In Baniyas – scene of a horrific Assadist massacre of some 500 Sunni civilians back in 2013 – armed civilians from the countryside, relatives of those prior victims – carried out the most appalling, savage massacre of the entire event, one of the more direct ‘boomerang’ events. Several Turkish-backed ‘Syrian National Army’ groups were regularly named as the most responsible for the massacres, as well as armed civilians. The new internal security forces, most directly under government control, were regularly cited as the most professional, attempting at times to help civilians escape, and focused on the actual insurgents. Calling these events a “government massacre” is lazy nonsense. UNHCR, Syrian government, Syrian Network for Human Rights and other bodies carried out investigations revealing some 1400 civilians were slaughtered.

The Syrian government condemned the massacre, got all the unauthorised forces out of the region within two days, and set up an investigation, which named 298 people on the pro-government side, including military and police, and 265 Assadist insurgents, to be investigated for war crimes. Just last week, the first 7 of each side were put on trial. This is a good sign. I do not have to have many illusions to say that such a thing never took place under Assad. This is progress. But without a radical change in government policy – not only the trials and punishment proving effective, but also compensation, real reconciliation and justice, and above all inclusion of the Alawite population in the political and especially security architecture of the new state, this component of the population is effectively lost.

While the slaughter ended, killings and kidnappings of Alawites has continued to be a major factor in the lives of the civilian population, although some killings are clearly targeted at former Assadist thugs who have not faced justice. There is both an undeniably sectarian element to this, but also a broader element connected to the post-revolutionary state of insecurity, which most leftists, particularly those who have studied history, need to admit is the norm; when you “smash the state” it takes time to rebuild from scratch and many civilians end up the victims of this state of insecurity. But the connection between the sectarian and purely insecure elements is precisely the reluctance, or extreme slowness, in today’s Sunni-led Syrian polity to incorporate significant numbers of Alawites into the security and military forces in the regions they live in, an essential step.

Even then, this state of insecurity should not be exaggerated for Syria today: for example, in the fact that in the week November 25 to December 2, of 41 violent deaths across Syria, a full third of them (13 deaths) were the result of Israel’s attack on Beit Jinn, another 22 percent (9 deaths) the result of unexploded ordinance (UXO), a gigantic problem in Syria today that is barely mentioned by anyone, and another 12 percent (5 deaths) caused by ISIS, highlights the fact that random killings have actually been in sharp decline for months – in the circumstances, something of an achievement.

One important point here is that while the March massacres mostly took place in the Alawite-dominated coastal governates of Tartous and Latakia (since that is where the Assadist insurgency took place), today these regions are relatively calm by overall Syrian standards. For example, in the fortnight October 28-November 11, Tartous and Latakia experienced the least violence of anywhere in Syria, including only one killing – that of an Alawite murdered by an Assadist-Alawite armed faction for working with the authorities! In contrast, Homs, despite being largely spared in March due to swift action by Syrian security forces to protect the Alawite population, remains stubbornly the worst region in Syria for this low-level, individual sectarian violence, reflecting the extreme sectarian tensions in a region where Alawites are a minority, but where, under Assad, the Sunni population was massacred and uprooted mercilessly.

While the government needs to do much more to incorporate the Alawites and stem the violence, the situation is not helped by the ongoing low-level Assadist insurgency which, while lacking popular support among Alawites who saw themselves left to the slaughter in March by the reckless insurgents, continues to kill security forces and sometimes civilians, perpetuating the sectarian atmosphere. Worse, one Alawite who stood in the October semi-elections, Haydar Younes, was labelled a ‘traitor’ and murdered by the insurgents; the Alawite candidate who won a seat in Baniyas (against 10 Sunni candidates) has allegedly fled the country due to threats from these quarters. On the other hand, a series of peaceful demonstrations by the Alawite community in late November showed that Alawites could raise their demands politically in new Syria, despite the odds, and point towards a better direction for Syria.

In some ways it is worse with the Druze massacre in July, because it was not precipitated by a murderous Assadist uprising, and in fact the Druze had mostly been anti-Assad and had begun the uprising against the old regime from 2023 onwards, and also because one might expect the government to have learned from the experience of March. I don’t have space to go into the same amount of detail here (read my article), but in short, the government’s responsibility for the Suweida massacre was greater than for the coastal massacre – not that I think it planned a massacre here either, but the attempt to use intervention into the Druze-Bedouin clashes as a means to militarily ‘solve’ the ongoing negotiation over the degree of autonomy and decentralisation for the region – by essentially taking the side of the Bedouin rather than separating the forces as announced – had consequences that should have been predictable. While Israel’s large-scale aggression to “protect the Druze” – including bombing the Syrian Defence Ministry building and national palace grounds – was self-serving and hypocritical, and the tendency of some Druze groups and leaders to raise the Israeli flag appalling, it is also to be expected when subjected to such savage, existential slaughter. While members of government military and security forces have been detained for future trials following the government’s investigation, it is too early to judge whether this will deliver impartial justice, and once again, as with the Alawites, given the sheer scale of the slaughter, without a radical change in governmental policy, this component of Syrians – previous to that a relatively pro-government one – is also lost.

One difference between the coastal and Suweida massacres was that since the Druze still had their armed militia, they were able to give government-backed forces a bloody nose; while figures of 1500-2000 are estimated to have been killed in the crisis, up to one third of these deaths were government-backed troops and security forces, along with Druze militia, Bedouin civilians (an often overlooked group) and Druze civilians (the vast majority of deaths). This means that Suweida is now effectively outside Syrian government control; it has its ‘autonomy’, but lives in limbo. While the UN and other aid agencies continually bring in supplies, private trade with the rest of Syria is almost impossible due to the state of insecurity between Suweida and Damascus, which the government seems either powerless to fix, or uninterested in fixing, making the situation effectively an undeclared siege.

The Druze political-religious leadership under Hikmat al-Hijri has taken a very hard line towards the Syrian state; it has set up its own ‘National Guard’ as a kind of para-state and rules out negotiating with current Syrian authorities. Al-Hijri had taken a hard line against the government throughout the year, buoyed by Israeli statements of support which he willingly responded to. However, blaming a ‘Hijri-Israel conspiracy’ for the crisis misses the point that the majority of the Druze leadership had taken a relatively pro-government and anti-Israel position and had continually disagreed with Hijri’s maximalism; but the massacre left mud on their faces and from then on all daylight between their position and Hijri’s vanished, except for some small groups who lack popular support. However, after months in limbo new voices have appeared calling for a different position out of pure pragmatism; Hijri however has demonstrated his own authoritarianism, with sweeping arrests of Druze oppositionists in early December followed by news that two of them, prominent clerics, Raed al-Mutni and Maher Falhout, had been tortured and killed in detention. It is also important to note that al-Hijri appointed former Assad-regime brigadier-general, and war criminal, Jihad Najm al-Ghouthani to head his ‘National Guard’! Further, in an October 11 letter to the UN Security Council, he referred to Suweida by the Hebrew name “Bashan” in a direct appeal for Israeli annexation.

Demonstrations calling for ‘independence’ or even annexation by Israel have no reality: Suweida’s population is around half a million, the region agricultural; independence would leave Druze communities elsewhere in Syria a smaller minority with no ‘centre’, while also leaving Suweida’s banished Bedouin population permanently outside; it has no border with Israel, and Israel frankly prefers Suweida in its current state of limbo as a dagger cutting into the heart of Syria serving its interests rather than the messiness of another illegal annexation, notwithstanding the fantasies of elements of the Israeli right about a ‘David Corridor linking the Israeli-occupied Golan to the Kurdish-led AANES statelet via Suweida, and from AANES to Iraqi Kurdistan.

Despite the effective Sunni domination of the new Syrian polity, the situation for other minorities is rather different to that of these two geographically-concentrated minorities. The Christian ten percent of the population has tended, despite challenges, to closely collaborate with the new authorities, who have also gone out of their way to work with their leaders; the small Ismaeli population has found its niche in new Syria, often as interlocutor between Sunni and Alawite communities; while even the small Shiite population has tended to be supportive of the new government, and aware of how cynically they were used by Assad and his allies in the past, though their situation varies throughout Syria. In between, we have the situation of the Kurds: like Alawites and Druze, their geographic definition gives their position a higher priority to the government, but their leaders have strongly oriented towards forming some kind of partnership with the post-Assad authorities.

We can only hope that the negotiations to integrate the Syrian Kurds, and the AANES statelet and SDF armed forces (not the same thing as ‘the Kurds’), into the Syrian state proceeds smoothly. For various reasons, the US has more invested in this process, given its 9-year alliance with the SDF against ISIS. Turkey tends to pressure the Syrian government to adopt a military ‘solution’; Israel prefers permanent separation and rupture. In between the two extremes of these two mutually-hostile US allies, the US position ends up a somewhat better one by default. While there are significant differences between the government and AANES/SDF, there has also been progress in bridging these differences. The SDF wanted to integrate into the Syrian army “as a bloc,” while the government wanted its troops to integrate “as individuals.” The deal is a compromise: some new army corp will be set up in the northeast, and so the SDF cadre will join them as large groupings local to that region; some AANES leaders will have ministries and some SDF leaders, like Mazlum Abdi, will get a high position in the Defence Ministry. Meanwhile, Sharaa has said that the local government law protects ‘decentralisation’ at the level of the AANES councils. We’ll see. Everyone knows that any military ‘solution’ here can only bring enormous catastrophe. Incidentally, while there are divisions on both sides regarding the approach to integration, PKK leader Ocalan has weighed in to express strong support to the SDF/AANES integrating into new Syria.

Meanwhile, while much left and progressive opinion tends to favour the Kurdish and SDF/AANES position – understandably given a number of very progressive aspects of policy, in particular being far in advance of current or previous governments regarding the role of women in society – it should be noted that they do themselves no favours with actions such as attempting to close Assyrian Christian schools (since rescinded), for teaching the government rather than the AANES curriculum, issuing a circular banning celebrations of the anniversary if the revolution, and statements earlier in the year opposing the lifting of sanctions (a position seemingly changed) and reaching out to Israel. A key problem with the issue is that much of the 30 percent of Syria that AANES/SDF rules over is not Kurdish, and in particular, much of the the Arab population in Raqqa and Deir Ezzor sees its future with the Syrian government; moreover, Deir Ezzor is where most of Syria’s oil is located, AANES thus holding a key Syrian resource. Arguably, a more flexible SDF policy may have been to more actively compromise on regions known to be chaffing under their rule (and indeed not doing so could end up having negative consequences for the SDF). But that goes for the government as well, for example, the refusal to budge on dropping the word ‘Arab’ from the country’s name, despite the opposition Syrian Coalition having agreed to do so as along ago as 2015.

Syria and the world: An oppressed, devastated country under foreign occupation and aggression

It is in the context of all of the above that the new Syria’s approach to the outside world must be seen. While it is appropriate that much of the domestic policy of the new government be heavily criticised (while also acknowledging great progress in many areas), as it is the government and, with al its limitations, does have power, when it comes to foreign policy, the framework must be different: whatever valid critiques can obviously be made, the framework is of a desperately impoverished, utterly destroyed country under one year of Israeli aggression and occupation, and still under US sanctions preventing recovery and reconstruction.

I will state this: I have found the level of white privilege among much of the western left on the issue of Syria’s foreign policy to be quite extraordinary.

Rather than express solidarity with Syria against Israel’s occupation and aggression, the privileged left condemns Syria for not “resisting.” Knowing full well that Israel destroyed Syria’s entire military arsenal in the first weeks. Knowing full well that any armed “resistance” at this stage would simply give Israel even more excuses to claim its occupation troops need the right to “self-defence” against the “terrorist jihadist” regime (Israel uses the same terms as some of the privileged left), and level Damascus. It is OK for you, but try to remember that much of Syria has already been levelled Gaza-style by Assad, Russia and Iran – it does not need more just at the moment, thanks.

Indeed, as noted above, when the people of Beit Jinn just did resist by merely injuring six of the invading occupation troops, the IDF responded with the airforce and killed 13 civilians. That is Israel’s model, as is well-known. Imagine that on a larger scale. Of course, as this incident shows, resistance will eventually grow because it cannot forever be held back against a brutal occupier, and when it happens they deserve our full support. But this is up to the Syrians themselves to determine when, how and how much, it is not up to computer-based, tyrant-worshipping, hypocritical western tankies. Given its enormous task of rebuilding a destroyed country, the government’s attempts to avoid this escalation through diplomatic means, especially through US government channels, is entirely sensible; Israel’s aim is precisely to provoke a military response so that it can openly continue Assad’s destruction of Syria.

Rather than express solidarity with Syria against Israel’s occupation and aggression, the privileged left proclaims, ignorantly (and usually wanting to stay ignorant) that Syria is trying to “make an agreement with Israel,” or even more ignorantly, that it is interested in signing the “Abraham Accords” with Israel, or that it is willing to give up the Golan Heights to Israel.

Trump’s ‘security agreement’ with Israel charade

Here are the facts:

The ‘security agreement’ that Trump wants (which, to be clear, has nothing to do with ‘normalisation’), is wanted neither by Syria nor Israel, but both go along with the discourse to try to get out of what they can from the US government, which ultimately has the power in the situation:

The Syrian government has endlessly issued the same message since December 8, 2024 when Israel ripped up the 1974 disengagement accord that Assad had stuck with for 50 years: that Israel must return to where its occupation forces were before that day. That is the only ‘security agreement’ Sharaa is willing to sign, ie, the exact same ‘security agreement’ that Assad signed in 1974 and stuck with forever after. If you cannot criticise Assad for never once attempting to go beyond the 1974 lines to liberate Golan in 50 years, with enormous armed forces, you can hardly criticise the new government for not gunning to do so in one year after Israel destroyed its military arsenal.

For Israel, on the other hand, if it is to sign any ‘security agreement’ with Syria, it has listed its demands: that it keep some of the extra territory stolen since December, especially Mount Hermon, that the UN buffer zone be extended some kilometres into free Syrian territory, that the entire south of Syria – Quneitra, Daraa and Suweida governates – be ‘demilitarised’ for Syrian military and air force, but that Israel control this airspace and be allowed to fly its own warplanes around at will to prevent “threats,” and that Syria cede the Golan. Syria rejects all of this out of hand.

Come on, privileged left – how about, good on you Syria for sticking to your guns?

The mainstream media circus does not help, of course. How ironic that we read phrases along the lines that Syria has been engaged in US-mediated negotiations with Israel “despite” Israel continually attacking Syria – that should be “because,” not “despite.” Countries under brutal aggression and occupation almost always have to negotiate with the aggressor; try thinking of any examples when that doesn’t happen. The privileged left condemns Syria for negotiating with its brutal occupier, while not condemning Hamas for negotiating, not condemning the Vietnamese for negotiating with the Americans – but on the other hand, demanding that Ukraine not only negotiate with the Russian imperialist aggressor and occupier, but also that it fully concede to Russia’s demands! Try making heads and tails out of this swill.

What is Trump’s position? Trump wants to be able to say he “ended another war” or some rubbish. But, despite his clownish friendly demeanour with Sharaa, lauding his “attractiveness” and so on, and his bending to the Gulf-Turkish position on Syria sanctions against the Israeli position, one thing is clear: ever since his first meeting with Sharaa in May, the US government has not once condemned Israel’s ongoing aggression against Syria. Trump’s flattery of Sharaa (mirroring what he likes to get) appears to be one of his means to achieve Israeli objectives, the good cop/bad cop show; though he may force Israel to concede just a little too, this is mostly about getting Syria to capitulate, to become a vassal. Moreover, only recently, Trump has yet again boasted about being the leader who recognised Syria’s occupied Golan Heights as Israeli territory. Syria is well aware of this duplicity.

Syrian government: No to normalisation with Israel, entire Golan must be returned

On the Golan itself, the privileged left proclaims, ignorantly, that the new Syrian government is willing to give up the Golan for “peace” with Israel. Yet the Syrian government has continually stated that it absolutely rejects conceding the Golan, continually stressing it is Syrian and must be returned and here in the UN, that its occupation by Israel enjoys no “Arab, regional or international legitimacy,” and again in Sharaa’s interview with Petreaus, and by Syria’s UN ambassador at an October Security Council session. When Trump, in a joint press conference with Netanyahu, boasted that he had “recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights,” Syria’s Foreign Ministry responded by reminding the world of UN Security Council Resolution 497 (1981) which declared the Israeli annexation “null and void.” The sheer wealth of such statements seems far more active than the Assad regime ever was on this question.

Rather than express solidarity with Syria against Israel’s occupation and aggression, the privileged left accepts and broadcasts, ignorantly, the media-driven discourse that the new Syrian government is open to signing the Abraham Accords and normalising with Israel, even though the government has not made a single statement that it wants to do so; second-hand hearsay is constantly contradicted by government leaders rejecting normalisation and the Abraham Accords, such as in Sharaa’s discussion with David Petraeus in New York, or here a few days earlier, or in this interview with Al Majallah in August, or here back in April, or in this interview with Shaibani, and in Sharaa’s interview with Fox during his November US visit and so on.

There is no basis for normalisation in any case, because Israel has declared Syrian agreement to cede the Golan a condition for any ‘normalisation’ with Syria, and Syria rejects that as a non-starter. But actually, the Golan gives Syria cover for rejecting ‘normalisation’ which it does not want in any case. In contrast to Assad’s explicit statement that Syria “can establish normal relations” if Israel returned the Golan (aiming to follow his Egyptian and UAE friends), that this has been his government’s position since negotiations began in the 1990s, the Sharaa government only speaks in the negative, that no discussion of normalisation is possible without the return of the Golan, that Syria’s foremost condition for any “peace process” to begin is a “complete Israeli withdrawal from the occupied Golan Heights”, that “Damascus will not consider any diplomatic initiative that falls short of restoring Syrian sovereignty over all occupied territory, including the entirety of the Golan Heights”; though in his interview with Petraeus, Sharaa also noted Syrian and global “anger” at Israel’s actions in Gaza as a further reason that normalisation is not on the cards. Unlike Assad, this wording makes no promise to normalise even if the Golan were returned; these are guarded statements to keep the US engaged.

I wrote about these issues here.

None of this means that partial surrender at some stage is impossible – when you’ve got a gun at your head you may be forced to make concessions, as has happened throughout history. As Dalia Ismail writes in Al-Jumhuriya:

“Yet this outcome [the prospect of forced ‘normalisation] is not freely chosen, but emerges from an impossible bind: either accept normalization, with Israel continuing to occupy Syrian territory, or face the ongoing threat of airstrikes, instability, and potential future invasions … what appears as diplomacy is in fact the formalization of coercion.”

Very good – but the important thing is that Syria has not capitulated.

Syrian foreign policy: ‘Balance’, no hegemony, no ‘blocs’

Sharaa’s US visit in November was full of contradictions. On the one hand, there was none of the public pomp, Sharaa entering the White House through a side door, to a meeting with no media; on the other hand, once over, sickening displays of Sharaa and that slug Trump almost slobbering over each other, giving gifts and the like, which was hard to watch. But aside from the show, and our feelings of disgust, what is this really about? Quite simply, alone in the world, only the US government holds two keys: that of ending its crippling sanctions, and that of at least somewhat restraining Israel. There is nothing more important to Syria. The two other issues discussed were Syria formally joining the 90-country alliance to combat ISIS – given that this war takes place on Syrian territory, it is probably a good thing, though the current Syrian government has fought ISIS from the outset anyway (as did HTS and all rebel groups for the last decade); and the ongoing integration negotiations with the SDF.

Does this mean Syria wants to join a “US-led axis” or any such thing, as many have charged? Let’s look at the timeline. Before meeting Trump in May, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov visited Damascus to meet president Sharaa and the foreign ministry in January, a few days later Putin had a phone call with Sharaa; after Israel’s stepped up aggression in July, foreign minister Shaibani visited Putin and Lavrov in Moscow, in September, a Russian delegation from 14 ministries visited Damascus and met a large Syrian delegation, in early October, a delegation of senior Russian military officials visited Damascus, to discuss Syria’s military hardware needs, then Sharaa visited Moscow and met Putin on October 15, and around the same time Shaibani announced an upcoming visit to Beijing in “early November.” Note – this is Russia, the state that ruthlessly bombed Syria for a decade on behalf of Assad, who it gives asylum to! So much for US axis! In fact, others are calling Sharaa a Russian asset!

It was in these circumstances that Trump made his sudden invite on November 10, upstaging Shaibani’s Beijing visit. But within days of Sharaa’s US visit ending, Syrian Defense Minister Murhaf Abu Qasra welcomed a large Russian military delegation, led by Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov, for talks in Damascus; on November 17, a convoy of about 30 vehicles carrying Syrian and Russian military officials made a field tour of Quneitra, visiting towns “where Israeli forces penetrate on an almost daily basis,” to assess possible Russian deployment in the region. And this took place on the same day that Shaibani was in Beijing, being feted by the Chinese foreign ministry and other top officials, who declared their support for Syrian recovery of the Golan, for Syrian participation in the Belt and Road Initiative, while Shaibani promised that no foreign fighters (ie Uyghurs) in Syria would be allowed to use Syrian territory to threaten Chinese interests, declared Syria’s support for the ‘One-China Policy’, and unfortunately, even made it explicit that this included Taiwan! Yes, Syria knows its reconstruction requires China’s economic might on board!

Condemn the Syrian government for often going completely overboard in its concessions, as long as you recognise that this is just as likely with Russian and Chinese interests as with American. Was it necessary to throw Taiwan under the bus so specifically? No, it was not. And we can think of many other occasions when the Syrian government went beyond the necessary, to the unnecessary, and damaging. And I would certainly like to imagine that a more revolutionary-democratic or socialist-oriented government would try to avoid such pitfalls, be more cognizant of the appeal to the world’s peoples rather than just the world’s ruling classes. Well and good. But this is what we have at the moment, and we must realise that even if we avoided all these excesses, the pressure would still be on any government to do a great deal the same.

Actually, Syria’s policy of refusal to be in any (imaginary) ‘axis’ or ‘bloc’ has been very explicit in countless statements by Sharaa and Shaibani. One sign is that it has used the term ‘strategic partnership’ with the US, Russiaand China alike. In a September interview with Sharaa in Al-Ikhbariya, after discussing growing relations with Russia, the interviewer notes Syria’s relations with the US and asks, “Where does Syria stand?” Sharaa responded that Syria had built good relations with the US, the West and Russia, and with Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and other countries, showing that Syria “bring(s) together the global contradictions,” due to “the strength of the event that happened” (ie, the overthrow of Assad). This “led to a balance in relations,” Syria “standing at an equal distance from everyone.”

Syria and Palestine

Finally, what about Palestine? I have already noted above the year of solidarity with Palestine in Idlib (I wrote about it here), but once Syria came under massive Israeli attack in December and January, the government initially went quiet, which was disappointing to say the least, though worth remembering that it was this government that freed hundreds of Palestinians, civilians and fighters, jailed by the Assad regime (those who survived Assad’s death dungeons). Sharaa returned to form in February, when asked in an interview about Trump’s plan to expel the whole population of Gaza, he called this a “very serious crime” and lauded the “80-year” Palestinian resistance to ethnic cleansing (note: 80-year, not 60-year), even taking aim at Trump’s planned expulsion of Mexicans from the USA as an analogy! Then in March at the Arab League Summit, Sharaa’s speech vigorously condemned Israel’s crimes in Gaza, West Bank and east Jerusalem, stressed Syria’s support for Palestinians struggle, including, crucially, for “return,” and stated that Syria would always stand by Palestine. And at the emergency OIC meeting in August, Shaibani condemned the “silence of global conscience” as Israel’s war crimes continue in defiance of international law and the UN Charter, by “bombing homes, hospitals and schools” which Syria condemns “morally, humanely and historically.” Finally, while most of Sharaa’s 10-minute UN speech naturally focused on his own country’s dire needs and Israel’s aggression against Syria, the only other issue in the world he gave the last part of his speech to was solidarity with Gaza.

Does this mean Syria will do anything to aid Gaza or Palestine? For the present, no, and it knows it cannot, which is also why its stance, while firm and principled, is not overblown; Syrians became allergic to Iranian-style bluster which used exaggerated “anti-Zionist” rhetoric to justify aiding in the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Arabs in Syria and Iraq while never doing anything of consequence in support of Palestine for decades (the “road to Jerusalem” always seemed to lead through Arab capitals like Baghdad and Damascus); they now prefer the gap between rhetoric and reality to be somewhat more smaller. Of course, we can say that Syria, under both Assad and Sharaa, shares the collective Arab betrayal of Gaza; but as a country under Israeli occupation itself, I think we can blame every other Arab country before Syria.

Why democratic gains are central to celebrate, to protect and to extend

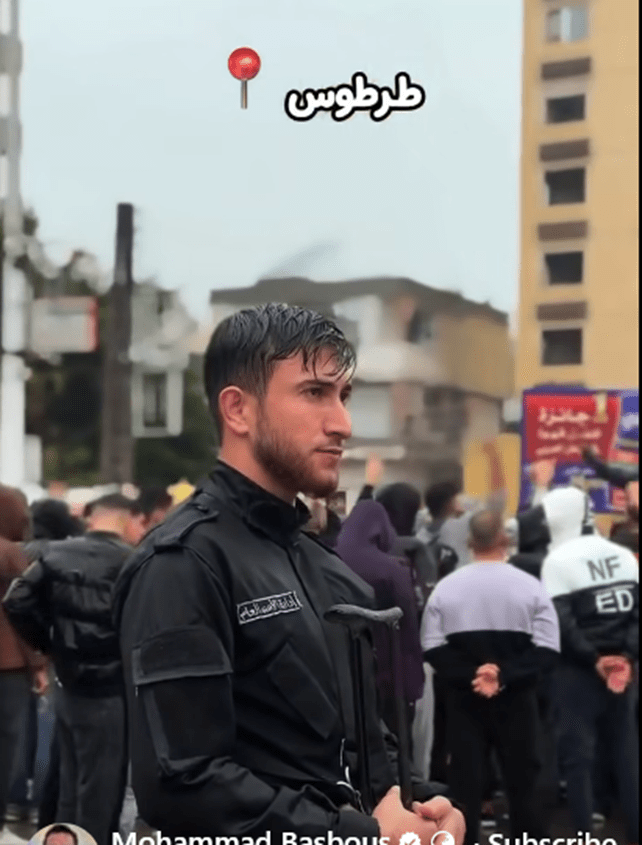

The widely shared video at the top of this article shows Syrian security officers guarding an Alawite demonstration in Tartous. The Alawites were demanding the federalisation of Syria, and the release of Assad-era officers who have been arrested to be charged with war crimes, though other Alawite demonstrations in the region the same day were merely condemning sectarian attacks on their brethren in Homs the previous days (these attacks followed the gruesome murder of two Sunni where the killers daubed the place with anti-Sunni sectarian slogans; this was later revealed by authorities to have been a set-up). I have no interest in trying to prettify the grim situation of the Alawites, as I have made clear above. For precisely that reason, despite believing the slogans at this particular protest were incorrect, the fact that a people who feel themselves oppressed in new Syria can demonstrate and be protected by state security is such a contrast to the Assad regime – which from the beginning of 2011 (and forever beforehand) reacted to peaceful protest with murder, incarceration, torture and disappearance – that it serves as one of the best symbols of the real difference that does exist between now and then. In addition, the fact that president Sharaa reacted by stating that the Alawite protesters had “legitimate demands” that he was “fully prepared to listen to” is also very encouraging – though of course actions speak louder than words.

I say all this without illusions, recognising that that there ARE violations of human rights and civilians’ democratic rights taking place under this government, including an occasional disappearance in an unmarked car, if on an infinitely smaller scale than under Assad; and without knowing whether or not this quasi-democratic opening will last; that is a question of struggle. But right now this picture tells an important story of what has been gained and what must not be lost, but rather radically extended.

This is the key gain of the revolution, and the test of whether we can continue to speak of ‘the revolution’ referring to the ongoing situation very much depends on this lasting and deepening; the moment the government were to open fire on a protest would be the moment it has lost all legitimacy and ‘the revolution’ could henceforth only be defined as the struggle against the new regime (indeed, this was the lesson of the early years following the Iranian revolution of 1979 where the Khomeini regime quite rapidly turned its guns on the revolutionary people).

We need to understand this centrality of democratic rights not only because it is a self-evidently just thing in and of itself. For all those opposed to many key aspects of the current situation, the authoritarian tendencies, the sectarian dimension, the neoliberal economic policy, the limitations on women’s role and so on, it is only the intervention of the people – through the growth of trade unions, the revival of civil society, through popular struggle, that any of this can change. Real change will come from below, not from imagining a ‘better’ party in power than (the long dissolved) HTS, and this can only happen if democratic rights are protected and extended.