By Michael Karadjis

At the end of my review of the domestic situation of post-Assad Syria, I cited the article ‘Is the new Syrian state revolutionary’, where Riad Alarian and Mohammed El-Sayed Bushra argue that since the Syrian state and its global support network have collapsed, the new leadership inherited a “proto-state with minimal military resources, no clear international partnerships, and a heavily sanctioned economy,” while facing domestic and foreign threats, therefore, regardless of intention or ideology, “there is simply no alternative to integration into global capitalism.”

They are correct that no country (especially devastated Syria) can survive isolated in today’s world. In any case, no-one ever envisaged Assad’s overthrow leading to non-capitalism; “integration into global capitalism” for Syria’s capitalist government would thus seem obvious. As I noted, a capitalist government will aim to stabilise the domestic situation for local and foreign capital, and sideline any radical or working-class challenge; but at the same time, the Syrian masses who entered the streets in December 2024 have expectations, see this as their revolution that began in 2011, and democratic space exists that did not before December, for them to speak, organise, hold rallies and the like without being repressed.

However, I also noted that both truisms – ‘capitalist government’ and ‘democratic space’ – need qualification, because Syria, after 14 years of genocidal war, is a destroyed country. Reconstruction of the millions of homes, thousands of hospitals, schools and essential services, entire cities and entire sections of the country, is first priority; and the return of the 14 million internal or external refugees (60 percent of the population) is bound up with this; they need somewhere to return to. Reconstruction and economic recovery will require massive local and foreign capital, loans and aid. Therefore, at this moment ‘stability for investment’ also equates with people’s needs. And there can be no working-class movement without some level of recovery of industry and infrastructure.

These qualifications apply equally to foreign policy. Much left-wing commentary expresses the meaningless truism that “a capitalist government will align with capitalist countries and pursue a non-revolutionary foreign policy.” Yet there are no non-capitalist powers in today’s world to integrate with even if the government were socialist; and revolution cannot be ‘spread’ by bluster, only by example.

Again, despite my overall agreement with Alarian and Bushra, that the conditions the new Syria emerged with “sharply delimited the horizon of revolutionary possibility,” their claims regarding the inevitability of certain foreign policy choices due to integration into ‘global capitalism’ are over-deterministic, especially their acceptance of the media-driven discourse claiming Syria’s leaders are open to the Abraham Accords.

My review below may seem less critical of the Syrian government than my review of domestic policy. The Sharaa government does have power inside Syria, with all its limitations; its soft-authoritarian, soft-sectarian and neo-liberal inclinations are policies representing the ruling wing of Syrian capital and conflict with the traditions of the Syrian revolution – despite these inclinations being constrained by the power of these traditions. In contrast, whatever criticisms can validly be made of Syria’s foreign policy must be seen in the context that Syria is a seriously oppressed and devastated nation, a state under occupation by several countries, especially Israel, which has engaged in endless aggression since Day 1.

This centrality of the Israel issue will be briefly introduced here, while more detail will be provided in the main body of the essay.

The centrality of Israeli aggression

Israel’s aggression against Syria began the day its preferred leader, Bashar al-Assad, was overthrown. In late February 2025, after an air attack on Damascus, Daraa and other towns – one of hundreds of air strikes and hundreds more land-based attacks since December – Syrians in Damascus marched to Umayyad Square demanding the government attack Tel Aviv!

Video here: https://x.com/RamiJarrah/status/1894537741578166678

So why doesn’t it? Why hasn’t the government militarily responded to Israeli aggression since December? Of course, it cannot resist air attacks; Israel destroyed Syria’s air-defence system, along with 90 percent of its military arsenal, in the weeks after Assad’s fall.

But leaving aside small-scale grassroots resistance, the Syrian government has not responded to the daily ground-based aggression either. If it did, Israel would declare its occupation troops have the right to ‘self-defence’ from the Syrian ‘terrorist’ regime, and level Damascus.

Now, ‘Axists’ may proclaim that when Hezbollah fired rockets at Israel in solidarity with Gaza, Israel responded by blowing south Beirut to pieces, so Syria should be prepared to suffer the same for the cause [these Axists though did not ask “why not Syria?” about the utterly passive Assad regime, which Netanyahu praised for 40 years of silence on the Golan].

However, before 2023, Hezbollah maintained a frozen border with Israel for 17 years, using the time to build its military arsenal, amassing 150,000 Iran-supplied missiles, while Lebanon rebuilt from its civil war. Whereas Syria has just emerged from 14 years of genocidal war, during which the Assad regime, backed by Russia and Iran (and Hezbollah while at peace with Israel) turned Syria into a moonscape, leaving entire cities and chunks of the country resembling Gaza, so the Syrian people cannot bear more just now; and as noted, Israel had just destroyed Syria’s military arsenal. The two situations could not be more different.

Israel has emerged as the number one enemy, Syria’s “main security threat.” How ironic that much shallow discourse – both from mainstream and ‘Axist’/campist ‘left’ media – claim that Syria-Israel ‘normalisation’ is on the horizon. There is a connection: while Israel calls the new Syria a “terrorist jihadist” enemy, its US ally made a sharp turn in May, from excruciating sanctions allied with Israeli aggression, to partially lifting sanctions to use the pressure of conditional economic engagement instead. Yet despite this, US leaders have not condemned Israel’s aggression. The point being that a key aim of US pressure (in both phases) is to force Syria to give up the occupied Golan and sign an even more humiliating ‘normalisation’ treaty with Israel than other states have.

This is not ‘peace’ between Syria and Israel, regardless of how treacherous that would be in normal circumstances; those who ‘made peace’ in recent years (UAE, Bahrain, Morocco) betrayed Palestine, but had no territory occupied by Israel; Egypt in its treacherous Camp David Accords of 1979 got its own Sinai back; Assad offered normalisation to Israel on the same basis. In contrast, Israeli aggression and US ‘friendly’ pressure today aims to formalise Syria’s submission.

Claiming the new Syria is ‘open to’ normalising with Israel could not be further from the truth. Condemning the victim of aggression and occupation for being forced into this dilemma is western ‘left’ privilege writ large. And that is apart from the fact that the Syrian government has made zero statements about being open to normalising with Israel in any circumstances, let alone without the Golan.

As Dalia Ismail writes in Al-Jumhuriya, this prospect of forced ‘normalisation “is not freely chosen, but emerges from an impossible bind: either accept normalization, with Israel continuing to occupy Syrian territory, or face the ongoing threat of airstrikes, instability, and potential future invasions; what appears as diplomacy is the formalization of coercion.”

Key goals and key principles of the new Syria’s foreign policy

This context is essential to understanding new Syria’s foreign policy, which includes two urgent goals, and two overriding principles. The two urgent goals are:

- ending US sanctions, which is essential to get the massive injections of foreign capital, aid or loans required for recovery and reconstruction

- ending Israel’s aggression and occupation beyond the 1974 disengagement lines.

The two overriding principles, aimed at meeting these foreign policy goals and crucial domestic goals (recovery, reconstruction, return, national unification) are:

- First, a pragmatic approach to foreign relations, including with countries previously friendly to Assad, and not making hair-brained attempts to “spread the revolution”. This is less ideological policy than survival mechanism, bound up with Syria being devastated and divided, with no money, little food or electricity, half the population displaced, no real army or military defence, a traumatised population, under quadruple foreign occupation and sanctions.

- Second, a refusal to be under the suzerainty of or aligned with any one power or ‘bloc’ of powers, but rather to balance between them; there is no intention of swapping Russian domination for another.

Is the new Syria part of a US-led, or reactionary, or capitalist ‘bloc’?

This second point is missed in most analysis, which often claims the very opposite.

For example, anti-Assad Syrian activist Joseph Daher (whose writings I strongly recommend) claims Syria’s rulers are “steering Syria towards a US axis” (which) would include “some form of normalisation with Israel.” In the excellent critical pro-revolution source al-Jumhuriya, Dalia Ismail claims that Syria is on a “path toward normalization with Israel and the broader US-aligned regional bloc.” Ismail explains that Syria’s choices cannot be understood outside “the combined weight of Israel’s military campaign and the crushing effect of Western sanctions” (which) “have left Syria structurally incapacitated,” and implies that Syria is buckling to this pressure. Syrian writer Shireen Akram-Boshar, while likewise stressing the context of Syria’s “weakened and largely devastated” reality, agrees that Sharaa is “aiming to join a reactionary status quo,” including some kind of “normalisation” with Israel. Finally, Alarian and Bushra’s acceptance of the media-driven discourse about the government’s alleged interest in the Abraham Accords is explained as an inevitable outcome of “integration into global capitalism.”

These claims that Syria is joining a “US axis,” “the broader US-aligned regional bloc,” “a reactionary status quo” or “global capitalism,” and that this inevitably leads to normalisation are highly problematic.

Firstly, given the government’s growing ties with Russia and China, are these countries part of a “US axis” or a “US-led regional bloc”? With the continual high-level meetings between Syrian and Russian leaders in Damascus and Moscow, many Syrians are making the opposite accusation, accusing al-Sharaa of being a Russian asset for cozying up to the state that bombed Syria for a decade.

Moreover, given the strong ties most of the alleged “regional bloc” (Saudi Arabia, Turkey, UAE, Egypt) have with Russia and China, does it make sense to call them a “US-aligned” bloc? Are there any coherent ‘blocs’ or ‘camps’ in today’s geopolitics? All the regional reactionary states furiously condemned Israel’s attack on Iran; none ever agreed to western sanctions on Russia over Ukraine (and neither has Israel). These countries are strongly divided among themselves on regional issues. Frankly, talk of geopolitical ‘blocs’ or ‘camps’ is half a century out of date.

Which are the non-‘reactionary’ states that Syria could align with to not be part of a “reactionary status quo”? Which countries could (capitalist) Syria ally with outside of “global capitalism”?

Finally, if being part of a “US-led Bloc,” a “reactionary status quo” or “global capitalism” makes normalisation with Israel inevitable, why then is there no consensus on Israel/Palestine among regional or global capitalist and reactionary states? ‘Global capitalism’ just voted by an immense majority of 142 countries in the UN General Assembly to support a Palestinian state, with only the US and some odds and ends voting with Israel. ‘Global capitalism’ walked out of the Assembly en-masse when Netanyahu spoke, including almost all the alleged “US-led regional bloc,” while Russia and China remained seated. The states closest to new Syria (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey) have not ‘normalised’ and/or have hostile relations with Israel. Israel and Turkey stand as enemies in Syria; why would Saudi Arabia pressure Syria to normalise with Israel when it steadfastly rejects normalisation without a Palestinian state based on 1967 borders? Egypt and UAE have normalised with Israel, but they had also normalised with Assad and are rather reticent in relation to new Syria. Russia and China, presumably outside a “US axis,” have excellent relations with Israel. Is BRICS outside a “US-led axis”? An alliance including Egypt and UAE, the most pro-Israel members of the “regional bloc”? Almost every BRICS member maintains relations with Israel.

Syria’s ‘no-bloc’ foreign policy

The Sharaa government’s ‘no-bloc’ foreign policy is actually rather explicit. One sign is that it has used the term ‘strategic partnership’ with the US, Russia and China alike.

In a September interview with Sharaa in Al-Ikhbariya, after discussing growing relations with Russia, the interviewer notes Syria’s relations with the US and asks, “Where does Syria stand?” Sharaa responded that Syria had built good relations with the US, the West and Russia, and with Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and other countries, showing that Syria “bring(s) together the global contradictions,” due to “the strength of the event that happened” (ie, the overthrow of Assad). This “led to a balance in relations,” Syria “standing at an equal distance from everyone.”

Similarly, Shaibani, when questioned in January about US and Russian bases in Syria, responded that Syria sees itself as “a point of balance” between superpowers that must never be used for “proxy conflict.” In October, he stressed that Syria’s foreign policy avoids alignment with any camp, Syria is not “in any axis.” Even when speaking of Sharaa’s upcoming trip to Washington in November, he stressed that Syria maintains “an equal distance with all countries.”

Broad outline of the new Syria’s foreign relations

When Assad fell on December 8, assumptions that states formerly aligned with the regime would be hostile to the new government and vice versa were not always warranted; the total disappearance of Assad’s regime meant that there was no way its friends could dream of restoring it, so some former enemies of the rebels sought pragmatic engagement.

- Syria’s most immediate close allies emerged as Turkey and Qatar, which had long supported the Syrian rebels and never normalised with Assad;

- at the other end of the spectrum, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which had normalised with Assad, reacted with suspicion towards new Syria, only cautiously accepting reality.

- In between was Saudi Arabia, which had earlier supported the rebels, lost interest and normalised with Assad; it switched back to emerge as new Syria’s third main ally.

- Israel emerged as the main enemy; despite its enmity with the Iran-led bloc, it understood that Assad’s regime was never a genuine ‘resistance’ regime and supported its maintenance against the opposition.

- The European Union early engaged with the new authorities and began lifting sanctions; in early May, Sharaa met French president Macron, who denounced Israeli attacks and called on the US to remove sanctions.

- The US, by contrast, steeped in the ‘anti-terrorist’, anti-Islamist and pro-Israel MAGA swamp, maintained a relatively hostile or sceptical stance the first 5 months, before a sharp switch in May.

- Among Assad’s two key backers, new Syria oriented to maintaining strong relations with Russia, which adopted an overtly friendly position to the government which had just overthrown its satrap (who it gave asylum to);

- whereas while both the Syrian and Iranian governments have sent signals to each other, the relationship remains cold (though there are divisions within the Iranian leadership).

- The government has also strongly engaged with China.

Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia

Turkey and Qatar immediately embraced the new authorities; due to its size, military power, long border and involvement with Syrian rebels, and with four million Syrian refugees inside its borders, Turkey was set to become a strategic ally. Israeli aggression also pushed Syria into military alliance with Turkey, which promised to train Syrian troops and re-equip Syria with air defence and other military assets. Yet this very size and proximity is also problematic due to the hegemonic influence Turkey could assert, especially regarding the Kurdish issue.

The first head of state to visit the new Syria was Sheikh Al-Thani of Qatar on January 30; Qatar is aligned with Turkey and the regional Muslim Brotherhood, which had a strong presence among sections of the Syrian rebellion. Yet the first country al-Sharaa visited was Qatar’s somewhat rival Saudi Arabia, on February 3. The first foreign minister to visit the new Syria, on December 22, was Turkey’s Hakan Fidan; yet the Syrian foreign minister’s first trip was to Saudi Arabia, on January 2.

While neither Qatar nor Turkey restored relations with Assad, Saudi Arabia did so and played a key role in getting Assad to the 2023 Arab League Conference in Riyadh. In ensuring a state as financially powerful as Saudi Arabia was on side, Al-Sharaa is balancing with the overwhelming Turkish influence. Saudi Arabia had held a midway position between the anti-Assad Qatar-Turkey alliance and the pro-Assad Egypt-UAE-Bahrain, thus it was a relatively easy decision to use engagement rather than hostility to influence new Syria.

Geostrategically, the Turkish Islamist AKP and the Qatari emir have been supporters of regional ‘Islamist’ movements – Islamist forces in the Syrian rebellion, the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt after the 2011 Egyptian revolution (which was overthrown by the Saudi-UAE-backed al-Sisi junta in 2013), the Islamist-linked government in western Libya after the Libyan revolution, the soft-Islamist Enhada in Tunisia, Hamas in Palestine – as their means of regional power projection; they attempted to ‘ride’ the Arab Spring to saddle it with a bourgeois-populist Islamist leadership, rather than trying to crush it. Turkiye sees a friendly neighbour as an economic opportunity, a stepping stone to influence throughout the Arab world, and a means of keeping the Kurdish movement in check. Saudi Arabia is back to where it was in 2011-2015, offering support both to compete with Qatar, and to project its influence as the leading Arab power, to prevent Syria passing from Iranian to Turkish hegemony.

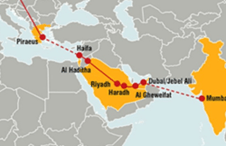

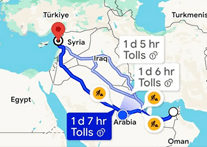

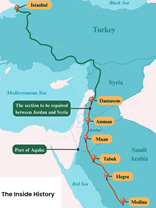

But Syria also represents geopolitical convergence, not only rivalry; both the Saudis and Turkiye see an open Syria as a strategic economic connection between the Gulf, its oil and gas, its Indian Ocean anterior and trade routes, with the Mediterranean and Europe. Syria as an alternative outlet to the Mediterranean (allowing Israel to be bypassed); while the original IMEC plans bypassed Turkiye, a route through Syria can incorporate it. All the more reason for Israel to hate an open and united Syria.

IMEC through Syria rather than Israel? Left: the original IMEC route; centre and right: road and rail routes from Gulf to Turkey and the Mediterranean through Syria.

Egypt, UAE: Reticence, but pragmatic acceptance

Assad’s former allies, the UAE and Egypt, both continued to express support to Assad even in his final days (as did Jordan) and showed strong reservations about the new government, but have cautiously recognised reality. The UAE’s arrest of a former Syrian rebel in April (as Sharaa was leaving after a visit), while granting asylum to former regime officials (even this Assadist who boasts of being part of the March 6 coastal insurgency) indicate the potential for problems ahead; in December, Egypt deportated Syrians who celebrated the fall of Assad in Cairo; in January, Egypt banned the entry of Syrians from anywhere in the world. However, there are few ‘al-Sisi coup’ options in Syria given the collapse of the old regime army, hence the cautious accommodation with al-Sharaa, but it would be wise to be wary of such ‘friends’.

Egypt-UAE caution represents the reverse of the Turkiye-Qatar position; the UAE, which bans the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation, which aided al-Sisi’s coup against the MB-led government in Egypt (after which he slaughtered 1000 MB supporters), which has assassinated hundreds of Yemeni MB cadre despite them being officially ‘allies’ against the Houthis, and which, alongside Egypt, aids the renegade warlord Haftar’s forces in eastern Libya against the Libyan government, and which normalised with both Assad and Israel, sees populist-Islamist movements as enemies, projecting power in this anti-populist manner.

Israel: Relentless hostility

From the start, Israel took a relentlessly hostile stance, immediately launching weeks of massive bombing to destroy virtually the entire military arsenal of Syria, which it had had no problem with while under Assad’s control. Throughout the Syrian conflict, Israeli leaders (political, military and intelligence) and think tanks continually expressed their preference for the Assad regime prevailing against its opponents, and were especially appreciative of Assad’s decades of non-resistance on the occupied Golan. Israel has for over a decade promised to do what it has done now if Assad were to fall and the rebels take power, to prevent them getting their hands on strategic weaponry. Israel invaded Syria beyond the occupied Golan and seized territory in Quneitra where Israeli leaders say they will remain (this extra annexation actually began two years previously under the Assad regime with regime and Russian connivance). It has constantly launched ground attacks further into Quneitra, Daraa and Damascus killing civilians who have attempted to resist. On December 29, Israel bombed Damascus and killed 11 civilians. Israel launched over 1000 air strikes and 400 land-based attacks in the year following Assad’s overthrow.

Israeli foreign minister Gideon Saar called the Syrian leadership “a gang of terrorists who took Idlib, then captured Damascus and other areas,” his deputy calling them “wolves in sheep’s clothing.” Netanyahu declared that Israel will enforce a complete demilitarisation of three Syrian provinces south of Damascus, barring Syrian troops, while offering “protection” to the Druze. With the March Alawite massacre, Israeli Defence Minister Israel Katz said al-Sharaa has “taken off his mask and revealed his true face: a jihadist terrorist from Al-Qaida,” while Saar condemned “the pure evil of jihadists.” On the March 15 anniversary of the onset of the 2011 revolution in Daraa, Israel attacked the town of Koya in Daraa and killed 6 civilians. In early April, Israel launched air strikes against Syrian military installations in Homs, Hama and the coast, partly to foil a potential Turkish deployment of anti-aircraft weaponry. In early May Israel attacked Damascus again at the presidential palace as a “warning” to Sharaa; Netanyahu said Israel “will not allow the extremist terrorist regime in Syria to harm the Druze.” In early June, Israel launched brutal air strikes in Daraa in “response” to some odd rockets landing in open spaces in the occupied Golan, and mass arrests and killings in Damascus countryside, alleging ‘Hamas’ presence. July saw the large-scale attacks on the Ministry of Defence building and the presidential palace grounds in Damascus, associated with the Suweida crisis; both arch-fascist Ben-Gvir and Israel’s Minister for Diaspora Affairs, Amachai Chikli called for assassinating Sharaa; Chikli called the Syrian government an ‘Islamo-Nazi regime’ and ‘Hamas’. August saw further strikes and ground-based attacks, killing Syrian troops, kidnapping civilians, claiming to be targeting ‘Hamas’ fighters and so on. November saw the Beit Jinn massacre of 13 civilians when the town attempted to resist and wounded 6 occupation troops. In December, Chikli declared that (open) war with Syria was “inevitable,” while aggression was stepped up, December seeing an average of 23 ground incursions per week, and 26 air and artillery strikes on Syrian territory, both a sharp increase on recent months. Aggression has not let up.

At a security conference in early 2025, Israeli leaders accused Turkey of “neo-Ottomanism,” asserting that a Syria run by Sunni Islamists allied to Erdogan could pose a greater problem for Israel than the Iran axis, warning Israel must prepare for war with Turkey. Israel also declared it wants to break up Syria into cantons, with Druze, Kurdish and Alawite statelets. Arch-fascist Smotrich has stated that conflict with Syria will end only when Syria is “partitioned.” This is not because Israel cares about minorities, but Israel sees region-based minorities as geopolitical opportunity to keep Syria weak and disunited; a convergence of minorities from the region was held in Israel in October.

Gideon Saar: “a gang of terrorists” seized Damascus; Israel Katz: “his real face: A jihadist terrorist from the Al-Qaida school;” Netanyahu: “extremist terrorist regime in Syria.”

The ‘normalisation with Israel’ media circus

Much noise has been made about whether the new Syria will “normalise” with Israel and “join the Abraham Accords.” This smoke and mirrors western media campaign (joined by Assadist and ‘Axist’ tankies), is a form of pressure on Syria, the psychological side of the hammer and anvil of Israeli aggression/US sanctions. Let’s get a few things straight.

- The Assad regime stated in 2020 that it would readily join its friends in the Arab world (Egypt, UAE) in signing a peace treaty with Israel if it withdraw from the Golan: “Our position has been very clear since the beginning of the peace talks in the 1990s … We can establish normal relations with Israel only when we regain our land … Therefore, theoretically yes, but practically, so far the answer is no.” Assad said nothing about Palestine or “resistance.” Both Assad senior in 1999-2000 and Assad junior in 2009-2011 engaged in serious US-mediated negotiations with Israel over such a Camp David-style agreement.

- The Assad regime bombed, besieged and starved Palestinian camps in Syria, especially Yarmouk, killing thousands of Palestinians. Fayez Abu Eid, director of the Working Group for Palestinians in Syria, revealed that “the number [of forcibly disappeared Palestinians] rose after updating the data to 7294 missing,” while 560 were released in December, and 1305 died under torture, thus the fate of some 5300 is still unknown. He said “the failure to find detainees in the regime’s prisons” suggests they were “liquidated,” raising “the number of Palestinians killed to more than 10,000 people, equivalent to 5.6% of the total Palestinians in Syria.” The regime jailed hundreds of Palestinian militants, especially members of Hamas; when Sednaya was opened in December, it was confirmed the regime had executed 94 imprisoned Hamas activists, including senior al-Qassem Brigades commander Mamoun Al-Jaloudi (executions continued after the Iran-forced cold ‘reconciliation’ between Hamas and Assad in 2022); only 67 Hamas cadres were released from Sednaya by the new authorities in December (including a leading al-Qassem commander), along with the leader of pro-Hamas Aknaf Bait al-Maqdis militia and dozens of fighters. Palestinians around the region began looking for relatives who had disappeared into Assad’s dungeons up to 40 years earlier.

- Throughout the Gaza genocide, the Assad regime, which stood apart from the “axis of resistance” in its complete passivity, engaged in intelligence cooperation with Israel, where Israel’s attacks on Iranian and Hezbollah targets in Syria were discussed; some Iranian sources suggest Israel got targeting information from the regime. Russia shared the skies with Israel and ensured that Syria’s air defences, which it controlled, never targeted Israeli warplanes bombing Iran-backed forces, as long as they left the regime alone.

- Throughout this time, the Assad regime banned pro-Palestine marches; the only regions where pro-Palestine demonstrations, seminars, fund-raisers etc were constantly held from October 7 2023 through December 2024 were those under opposition control in Idlib and rural Aleppo, organised by HTS and other rebels, one campaign raising $350,000 for Gaza, a remarkable achievement for a poor rural province under Assadist siege; April 2024 saw the opening of ‘Gaza Square’ in Idlib.

- Despite the media hype, the government has not made a single statement that it wants to ‘normalise’ with Israel; second-hand hearsay is constantly contradicted by government leaders rejecting normalisation and the Abraham Accords, such as in Sharaa’s discussion with David Petraeus in New York, or here a few days earlier, or in this interview with Al Majallah in August, or here in April, or in this interview with Shaibani, in Sharaa’s interview with Fox during his November US visit.

- There is no basis for normalisation in any case, because Israel declared Syrian agreement to cede the Golan a condition for any ‘normalisation’ with Syria, whereas the Syrian government – despite constant, laughably false, media speculation – absolutely rejects conceding the Golan, continually stressing it is Syrian and must be returned (and here, and here), that its occupation by Israel enjoys no “Arab, regional or international legitimacy,” here again in Sharaa’s interview with Petreaus, and his interview with CBS, and by Syria’s UN ambassador at an October Security Council session. When Trump recently boasted that he had “recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights,” Syria’s Foreign Ministry responded by reminding the world of UN Security Council Resolution 497 (1981) which rejected Israeli annexation.

- The Golan gives Syria cover for rejecting ‘normalisation’ which it does not want in any case. But in contrast to Assad’s explicit statement that Syria “can establish normal relations” if Israel returned the Golan, the Sharaa government speaks in the negative, that no discussion of normalisation is possible without the return of the Golan, that Syria’s foremost condition for any “peace process” to begin is a “complete Israeli withdrawal from the occupied Golan Heights,” that “Damascus will not consider any diplomatic initiative that falls short of restoring Syrian sovereignty over all occupied territory, including the entirety of the Golan Heights.” This wording makes no promise to normalise if the Golan were returned; these are guarded statements to keep the US engaged. In his interview with Petraeus, Sharaa also noted Syrian “anger” over Gaza was another reason normalisation is not on the cards.

US-mediated negotiations for a ‘security agreement’ with Israel have led to much confusion, with various sources conflating such an ‘agreement’ with ‘normalisation’. Sharaa and others continually stress that the two are unrelated. Moreover, Syria, Israel and the US have different ideas about this purported ‘agreement’.

- The only ‘security agreement’ the Syrian government will sign is one whereby Israeli troops return to where they were on December 8 and the previous 51 years, since the ‘security agreement’ Assad signed with Israel in 1974. Since December 8 Israel has violated it; the Syrian government has continually made the same demand: return to the 1974 disengagement lines. The Syrian government therefore needs no new agreement, but Israel’s violation of it forces it to take part in the US ‘security agreement’ charade.

- Israel demands a new agreement to include it retaining some Syrian land stolen since December, especially Mt Hermon, expansion of the buffer zone further into Syria, three demilitarized zones (for the Syrian military and airforce) in the south, extending to Damascus, and Israeli control the air space in the south, with ‘flyover’ rights for its warplanes; Syria rejects these violations of its sovereignty.

- Trump wants this unnecessary ‘security agreement’ in order to claim to have “ended another war” between enemies; to smooth over the irreconcilable positions of Israeli on one hand and Turkiye and the Gulf on the other; and to pressure Syria to at least partially capitulate to Israel’s terms; Trump may force some Israeli ‘compromise’, to demonstrate ‘impartiality’, but any concession to Israeli terms represents absolute Israeli victory over the pre-December situation, and over Syrian sovereignty.

These are ‘negotiations’ between an economically and militarily powerful state, and an impoverished, destroyed country which the former is occupying and attacking daily, and must be seen within this framework. There is no ‘principle’ that a country under occupation does not negotiate with the occupier; that almost always happens, on unequal terms. The ‘anti-imperialist’ discourse condemning Syria for not plunging the country back into devastating war by ‘resisting’ the occupation, or even for merely negotiating, are speaking from extreme privilege and entirely missing the point; shallow analysis in mainstream media does not help. Rather than heroic ‘condemnation’ from laptops, western leftists who understood the concept of solidarity should be giving it to Syria.

In any case, Syria has refused to surrender to Israel’s demands on this security agreement (let alone the Golan). For weeks there was speculation that Syria and Israel would sign a ‘security agreement’ during the UN General Assembly in September; there was even patently absurd media-invented talk of Sharaa meeting Netanyahu there. Sharaa’s UN speech, condemning Israeli aggression and expressing solidarity with Gaza, was listened to by the whole assembly, while Netanyahu gave a blood-curdling speech to an empty hall. Sharaa’s interview with Petraeus was equally firm. New Syria came away with its head high, but Israeli aggression continued. Following this, the US downgraded its short-term expectations to a ‘de-escalation agreement’, whereby Israel would stop bombing Syria (but not withdraw) while Syria would not move heavy weaponry to the south.

The Syrian government’s participation in negotiations to ‘de-escalate’ and statements that Syria is too ‘exhausted’ for renewed conflict and is ‘not a threat’ to its neighbours are not aimed at reassuring Israel, but rather at the US, in the hope of the US pressuring Israel to lower the temperature, and for it to continue slowly lifting sanctions. Israel knows exactly what it is doing; it knows that Syria cannot pose a ‘threat’ even if it wanted to; its aims are precisely to prevent the Syrian government from stabilising the situation and uniting the country which Israel wants to dismantle. And Syria knows that Israel knows what it is doing.

Holding out is difficult – who will invest in a country’s reconstruction where active war continues, where your investment may get blown up? As Sharaa put it in September, “If you’re asking whether I trust Israel, no, I don’t trust them. Israel’s attacks on the Presidential Palace and Ministry of Defense buildings constituted a declaration of war. Syria knows how to fight but no longer wants to. However, we have no choice but to reach a security agreement with Israel.”

Syria’s dilemma is: agree to Israel’s conditions that violate Syrian sovereignty, or reject them and Israel continues attacking and bombing, with US connivance despite Trump’s Janus-faced smile.

Syria and Palestine

The year of solidarity with Palestine in Idlib and free Aleppo has been discussed above; all wings of the Syrian revolution had always identified with the Palestinian struggle so this was not really surprising; still less surprising are the links between specifically Islamist sectors of the Syrian rebellion and Palestinian Islamists like Hamas, and their links with the Erdogan regime in Turkey and the regional Muslim Brotherhood; add to this the mass release of Hamas and other Palestinian militants by the new government from Assad’s dungeons. However, once Syria came under massive Israeli attack in December and January, the government initially went quiet on Palestine, likely based on the hope that doing so might encourage US and European leaders to pressure Israel to back off. If so, it didn’t work.

Sharaa returned to form in February. Lauding the “80-year” Palestinian resistance to ethnic cleansing (note 80-year, not 60-year), he called Trump’s plan to expel the population of Gaza a “very serious crime” and even slammed Trump’s planned expulsion of Mexicans from the USA as an analogy. At the Arab League Summit in March, Sharaa’s speech vigorously condemned Israel’s crimes in Gaza, West Bank and Jerusalem, stressed Syria’s support for the Palestinian struggle, including specifically for “return,” and stated that Syria would always stand by Palestine. At the emergency OIC meeting in August, Shaibani condemned the “silence of global conscience” in the face of Israel’s war crimes of “bombing homes, hospitals and schools” which Syria condemns “morally, humanely and historically.” Then while most of Sharaa’s 10-minute UN speech naturally focused on his own country’s dire needs and Israel’s aggression against Syria, the only global issue he gave part of his speech to was solidarity with Gaza. And when asked by Christine Amanpour about his “terrorist” past in a December interview, Sharaa claimed instead that the terrorists are those who killed 60,000 Palestinians in Gaza (and those who killed civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan while labelling others as terrorists, a subtle swipe at the US), and said Israel’s attacks on Syria are partly aimed at “evading responsibility for the massacres it is committing in the Gaza Strip.”

Does this mean Syria will do anything to aid Gaza or Palestine? For the present, no, and it knows it cannot, which is also why its firm and principled stance is not overblown; Syrians became allergic to Iranian-style bluster which used exaggerated “anti-Zionist” rhetoric to justify aiding in the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Arabs in Syria (and Iraq in the 1980s) while never doing anything of consequence in support of Palestine for decades (the “road to Jerusalem” always led through Arab capitals like Baghdad and Damascus); they now prefer a smaller gap between rhetoric and reality. Of course, Syria, under both Assad and Sharaa, shares the collective Arab betrayal of Gaza; but as a country under Israeli attack and occupation itself, we can blame every other Arab state before Syria.

Iran: Relations still frozen, despite feelers

Iran is the other opponent of new Syria, though this is inconsistent. On one side, leaders around president Pezeshkian have taken a pragmatic approach to the new government; in January, Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said that Iran respects “the Syrian people’s will to decide their own fate without foreign interference;” in April, Deputy Foreign Minister, Saeed Khatibzadeh, said Iran is “ready to provide support and assistance” to the new Syria. There are ongoing indirect talks via Turkey, Qatar and Iraq. Iran’s embassy staff left Syria after December 8, for security reasons, and anticipate returning sometime; Syria has maintained its ambassador in Tehran.

In contrast, those close to Khamenei and the IGRC leadership dream of vengeance. In January, Iran’s top commander in Syria, Brig. Gen. Behrouz Esbati, condemned the Assad regime for sabotaging the Iran-axis fight with Israel, yet echoed Khamenei’s call for “resistance” against the new government, claiming “we can activate all the networks we have worked with over the years,” and “the situation there will not remain unchanged.” A few days before the Assadist insurgency in March, the Iranian Mehr Newsagency released a statement from the Islamic Resistance Front in Syria – Uli al-Baas, urging Syrians to revolt. There were no explicit Iranian fingers on the insurgency and Iran denied it (and Alawite insurgents condemned Iran for not helping). However, General Suleiman Dalla, a commander of the notorious Fourth Brigade linked to Iran during the war, was a key insurgent leader.

As Assad was falling, Sharaa called on Iran to “reconsider its relations” with the regime and support the Syrian people, stating Iran can establish “strategic relations with Syria in the correct way.” In January, he stated that Syria “cannot continue without relations with an important regional country like Iran.” The Syrian government has lived up to its promise made to Iran in December, as it withdrew its forces, to protect the Shiite community and Shiite shrines. In January, the HTS-led public security arrested ISIS operatives planning to attack the Shiite shrine in Sayyida Zeinab, after being tipped off by US intelligence.

However, relations remain cold. If Iran wanted to improve ties, it could start by dropping its grotesque $30 billion claim on Syria for lost ‘investment’ in the Assad regime to help it commit genocide; this claim was recently reissued, despite Iran’s Foreign Ministry acknowledging that Assad embezzled these funds!

Russia: Active engagement with former arch-enemy

In January, Syria banned citizens of Iran and Israel from entering the country; despite then banning goods from Israel, Iran and Russia, Russia made a number of desperately needed oil shipments to Syria over the next few months. What is this about?

Russia bombed Syria for ten years on behalf of Assad’s tyranny, specialising in destroying hospitals, even using ‘bunker busters’ to bomb hospitals built underground; this is hard to beat in earning the eternal hatred of the Syrian people. However, both the Sharaa government and Russia have continually expressed the desire for good relations.

Already on November 29, 2024 as the rebels launched their offensive, HTS announced that “the Syrian revolution has never been against any state or people, including Russia,” but merely aims “to liberate the Syrian people from … the criminal regime,” calling on Russia “not to tie [its] interests to the Assad regime, but rather with the Syrian people” as “we consider [Russia] a potential partner in building a bright future for free Syria.” This was a brilliant appeal to avoid unnecessary bloodshed.

On January 28, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov visited Damascus to meet president Sharaa and the foreign ministry, a few days later Putin had a phone call with Sharaa, and then Syria abstained on the UN General Assembly vote to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine (though arguably it was simply joining the Arab world’s bloc vote, a misguided way of protesting US support for Israel in Gaza). During his call with Putin, Sharaa emphasised “the strong strategic ties between the two countries.”

Unlike Iran, Russia is a superpower on the UN Security Council, so Syria needs it onside to get the ‘terrorism’ designation removed; and as Sharaa stated, “all of Syria’s arms are of Russian origin, and many power plants are managed by Russian experts. We do not want Russia to leave Syria in the way that some wish.”

Following Israel’s large-scale attacks on Damascus during the July Suweida crisis, Shaibani visited Moscow and met Lavrov and Putin. Shaibani stated Syria wanted Russia “by its side,” thanking it for its “strong position in rejecting Israeli strikes and repeated violations of Syrian sovereignty,” while Lavrov thanked “Syrian colleagues” for ensuring “the safety of Russian citizens and Russian facilities” in Syria. In September, a Russian delegation from 14 ministries visited Damascus and met a large Syrian delegation; Shibani described Syrian-Russian relations as “deep, having gone through stages of friendship and cooperation, though lacking balance.” He said that any Russian bases “must serve the Syrian people in building their future,” in contrast to the past. He called for Russian cooperation in reconstruction, energy, agriculture, and health on a “fair and transparent” basis. Then in early October, a delegation of senior Russian military officials visited Damascus, to discuss Syria’s military hardware needs, following a Moscow visit by Syrian Defence Ministry officials.

Sharaa met Putin in Moscow on October 15. He was already expected in Moscow for a planned Russia-Arab summit that month, which Putin postponed when Trump’s Gaza ‘peace’ plan stole the limelight and no Arab leaders could confirm their attendance – with the sole exception of Sharaa! Talks focused on “revising old agreements signed under Assad, exploring investment opportunities,” the “future of Russia’s military installations,” and “rearming the Syrian army;” “the delivery of humanitarian aid, medicines and wheat,” projects in “the energy, transport and tourism sectors,” Russian help developing Syria’s oil fields, and Syria’s demand that Moscow extradite Assad.

The Syrian government expressed support for Russian patrols returning to southern Syria to help stabilise the Golan situation to give Israel less excuses for aggression and to add pressure on Israel to withdraw from territory recently seized. Just days after Sharaa’s high-profile meeting with Trump in Washington – as if to really emphasise the ‘balance’ policy – Syrian Defense Minister Murhaf Abu Qasra welcomed a large Russian military delegation, led by Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov, for talks in Damascus; on November 17, a convoy of about 30 vehicles carrying Syrian and Russian military officials made a field tour of Quneitra, visiting towns “where Israeli forces penetrate on an almost daily basis,” to assess possible Russian deployment in the region.

Sharaa knows Israel trusts Russia; ironically, while Sharaa tries to enlist Russia against Israel, Israel insists that Russia maintain its bases (Israel demanded the US not condition sanctions relief on Russia being evicted). Israel was happy with Russia’s presence in the region when it was backing the Assad regime, while protecting its Golan occupation from pro-Iranian forces, because it preferred that regime in power. Now, however, Israel is hostile to the new Syrian government itself. Israel knows that Syria is in no state to send Sunni ‘jihadis’ or Palestinian militants to the Golan, and that pro-Iran forces are gone. These are mere excuses for Israel to occupy the region, destabilise the Sharaa government, and grab territory; so a Russian offer now to protect Israel’s Golan occupation along the UN lines is a threat to Israel, removing its excuse for further occupation; Israel has no interest in returning to the 1974 lines.

Russia’s aim is to maintain its Mediterranean air and naval bases in Tartous and Latakia. If both Israel and the Syrian government want it in from opposite angles, Russia is happy to be all things to all sides. While Russia will do nothing to protect Syria from Israeli aggression, its rivalry with the US leads to ritual statements of support for Syria’s “sovereignty and territorial integrity,” which while meaningless, easily look better than the uncritically pro-Israel US position.

Links between Assadist elements on the coast and Russian forces in these coastal bases are widely suspected; either way, in any future souring of relations or governmental crisis, the presence of Russian bases (or Russian forces in the south or in the Qamishli airport) offers huge destabilising potential.

It is difficult to fault the Syrian government for wanting Russia to provide ‘balance’, however distasteful for Syrians that their mass murderer is still involved in their country. Looking around the region and the world, there are few good choices.

China: “Vast common interests”, but also issues

In April, Shaibani met China’s UN ambassador, Fu Cong, in New York, stating that Syria wanted a “long-term strategic partnership” with China. After Trump’s May sanctions announcement, Syria signed a major investment agreement with Chinese company Fidi Contracting, granting it a million square metres of free trade zones to build “a fully integrated industrial zone containing specialized factories and production facilities” in Homs and “commercial and service projects” in Damascus. This highlights the importance Syria attaches to China as a global economic powerhouse, given its massive needs. The timing of Shaibani’s July 27 meeting ambassador Shi Hongwei, before his trip to Moscow, was connected to Israel’s stepped up aggression, which Shi condemned; Beijing stresses that “the sovereignty, independence, unity, and territorial integrity of Syria should be respected.” Announcing his state visit to Beijing in November, Shaibani stated that Damascus “needs genuine strategic partnerships – especially with China – during the phase of building and reconstruction.”

For Beijing, Syria’s importance is connected to its pivotal location as an exit point for its BRI project across Asia into the Mediterranean and Europe (though Beijing is not choosy, given its part-ownership of Israel’s Haifa).

Aside from China’s economic might, China is also of interest to Syria to balance both the US, with its Israel problem, and Russia, with its Assad problem; being more distant and comparatively uninvolved in Syria compared to these powers, China potentially offers fewer problems. However, China relations do have the problem that some of the “foreign fighters” remaining in Syria are Uyghurs, including roughly 2,000 to 5,000 Uyghur militants from the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP), based on 2018 estimates, many of whom fought in HTS or other Islamist ranks against Assad. These fighters are now being integrated into Syria’s armed forces, several promoted to high ranks.

China has been urging action against them in the UN Security Council. In March, it demanded Syria’s leaders “fulfill their counter-terrorism obligations” and “take decisive measures” against TIP. Syria’s response is that by integrating them into its army, they will be less troublesome than if outside state bodies. Expelling fighters who helped bring down Assad is not an option; and if expelled they would likely head for Xinjiang. Following the announcement of Shaibani’s trip to Beijing, one report claimed “several individuals suspected of belonging to the Turkistan Islamic Party” were arrested, “as a direct response to China’s concerns,” but I have seen no confirmation of this.

Shaibani’s state visit to Beijing took place on November 17 – soon after Sharaa’s meeting with Trump, and on the same day as the Russian military tour of the south – meeting China’s foreign minister Wang Yi and other top officials. A joint statement said the two countries had “vast common interests.” Yi offered China’s participation in Syria’s reconstruction, while Shaibani praised China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Stressing cooperation against “terrorism,” Shaibani assured that Syria “would not let any entity use Syrian territory for actions against Chinese interests.” He also emphasised Syria’s support for the One-China policy, “recognizing Beijing as the sole legitimate government representing China, including Taiwan,” while China reaffirmed that the Golan Heights remains Syrian territory (Fu Cong strongly asserted this again at a UN Security Council meeting two days later, and demanded Israel immediately return to the 1974 lines, and demanded the end of all “unilateral” sanctions on Syria). An AFP report that Syria planned to hand 400 Uyghur fighters to Beijing was denied as “without foundation” by Syria.

United States

Phase 1: December to May – US indifference and/or hostility

Despite some ground-level engagement against ISIS and to facilitate government engagement with the SDF, until mid-May the US position remained cold, influenced by Israel and key White House and NSC Islamophobes and ‘anti-terrorism’ tsars in MAGA circles, including Trump’s director of counterterrorism Sebastain Gorka (who has “never seen a jihadi leader become a democrat”), Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard (who visited Assad in 2017), and Israel-connected National Security Advisor Mike Waltz (whose removal “cut off a chunk of the White House’s ‘wall of resistance’ on Syria”); MAGA acolytes like VP Vance, Elon Musk, and Tucker Carlson were of a similar mindset. Just days before Trump’s sanctions announcement, Gorka condemned the Syrian government as “salafi-jihadist.” As Syria watcher Charles Lister writes, “For 5 months, the entirety of President Trump’s national security apparatus — from the National Security Council, to the State Department and intelligence community — has voiced varying degrees of hostility, scepticism and/or indifference to Syria’s post-Assad transitional government.”

In April, the US labelled Syria’s UN mission “the mission of a country the US doesn’t recognise.” In February, of 23 European and Arab countries at the Paris Conference to support Syria’s transition, only the US did not sign the declaration (due to “reservations the US has on HTS”). In an April 10 UN Security Council session amid Israel’s aggression, only the US took Israel’s side, as “Israel has an inherent right of self-defense, including against terrorist groups operating close to its border.”

While the EU statement on the coastal violence condemned both the Assadist coup and the sectarian slaughter of Alawites, the US State Department did not mention the former, condemning only “radical Islamist terrorists, including foreign jihadis, that murdered people in western Syria,” declaring the US “stands with Syria’s religious and ethnic minorities, including its Christian, Druze, Alawite, and Kurdish communities,” an odd statement excluding Syria’s Sunni majority since these non-Alawite minorities were not being killed. The US and Russia jointly called a UN Security Council meeting.

Just days before his Gulf trip, Trump reported to Congress that the Syrian ‘national emergency’ sanctions would be extended another year, because “structural weakness in governance inside Syria, and the government’s inability to control the use of chemical weapons or confront terrorist organizations, continues to pose a direct threat to U.S. interests.”

Phase 2: May-July – Trump’s sanctions announcement and US engagement

Trump’s abrupt mid-May announcement during his Gulf extravaganza that sanctions would be lifted left many in the White House, including officials tasked with implementing the policy change, completely unprepared. This move was no gift; maintaining the sanctions on the Assad regime for 5 months after that regime collapsed made no logical or legal sense; it was an act of violence against the Syrian people and their new government. What were the driving forces behind this turnaround?

The first was geopolitical; that Trump announced the lifting of sanctions (and met Sharaa) in Saudi Arabia during his Gulf show highlights his bending to the pressure of Saudi Arabia, Qatari and Turkiye (who want to invest and make money) against that of Israel, which lobbied Trump to not lift sanctions; Trump, announcing the move, exclaimed “the things I do for the [Saudi] Crown Prince.” This regional rebalancing also saw Trump’s non-aggression deal with the Houthis (with no mention of their attacks on Israel), opening negotiations with Iran, and direct meetings with Hamas to get a US citizen-hostage released – all balanced, however, with ongoing total US support to Israel’s main cause, the annihilation of Palestine.

Second, the US was simply slower than the regional regimes, the EU and Russia in recognising there was no ‘al-Sisi solution’ given the collapse of the old armed forces. As such, Sharaa’s ‘pragmatism’ became the ‘only hope’ to keep the country together; the government’s collapse would lead to chaos and the explosion of extremist jihadi factions. Rubio predicted the government was “weeks away from potential collapse and a full-scale civil war of epic proportions.” If US regional allies, and US companies, are to invest in Syria, they want the country held together. Lifting sanctions faciliatates this investment and creates conditions for stabilising the situation; Gulf, Turkish and US economic engagement replaces enforced absence of economy as the new form of conservatising pressure on post-revolutionary Syria. As leading US Treasury official, John Hurley, put it, by investing in Syria’s reconstruction, Turkiye and the Gulf “could create substantial hope for peace there.”

Trump’s decision led to several large-scale investment announcements, especially the $7 billion Qatari-Turkish investment in Syrian energy infrastructure, alongside Saudi, Emirati, French and Chinese projects.

This connects to the third aspect, Trump’s preference to withdraw most of the 2000 US troops in the northeast working with the SDF (Sharaa called this US presence “illegal”). However, the US does not want withdrawal to lead to Turkey attacking its Kurdish allies to force a ‘military solution’, as it threatens to; but neither has the US ever supported Kurdish independence (and this is not the SDF project). Meanwhile, Israel’s preference for partitioning Syria means it opposes the government-SDF March 10 integration agreement from the opposite angle to Turkey. Therefore, the US position balancing between its Israeli and Turkish allies ends up a somewhat positive one in support of the March agreement and a negotiated integration (SDF leader Mazloum Abdi travelled to Damascus aboard a US military aircraft to sign the agreement).

While this is sometimes misinterpreted as the US ‘betraying the Kurds’, precisely the opposite is at play: having worked closely with SDF leaders for a decade, the Pentagon sees their integration into the Syrian military as a buy-in to the regime whose Islamist credentials it remains suspicious of. As John Hannah, a senior fellow at the hard-right US think-tank Jewish Institute for National Security of America (JINSA) put it, just after a wayward jihadist within the Syrian army broke ranks and killed several US troops, “The SDF have been America’s most reliable and effective partner in fighting ISIS for more than a decade. The logic of incorporating those SDF units wholesale into al-Sharaa’s army and then unleashing them with U.S. backing on the ungoverned spaces of Syria’s central desert where ISIS has found real sanctuary is compelling.”

In any case, this US position is simple logic in connection with the previous aspect above: investors need a united country. US envoy Tom Barrack made this clear to both parties when he walked out of a government-SDF meeting where no agreement could be reached, stating no US funds would be invested in Syria until some agreement was reached, patronisingly claiming the US was bringing them together “like two kids in a playground.”

The fourth aspect is the US war on ISIS, even with reduced presence; with the US coordinating with the SDF but now also working with the government against ISIS, it logically prefers a united Syrian anti-ISIS response, rather than two anti-ISIS sides fighting each other.

That the US sees the possible collapse of the Syrian state as a concern indicates that its broader regional view – aligned with Gulf and Turkish interests – contrasts with Israel’s narrower interests and preference for a divided and collapsed Syria. However, reality is not so straightforward.

First, despite the outwardly friendly attitude to Sharaa and the sanctions announcement, there has since been no US statement demanding Israel halt its bombing and occupation. The US sees this as useful pressure for Syrian capitulation. Trump has recently boasted that he recognised Israel’s annexation of the Golan, as have other US leaders such as Witkoff, as if oblivious that these are hostile statements. Syrian leaders are aware of this duplicity. The US-Israeli difference thus contains a ‘good cop bad cop’ element.

Second, before Trump’s announcement, the US had made a list of conditions for mere sanctions “relief.” Some were easy (cooperation against ISIS and on chemical weapons) while Syria claimed others infringed national sovereignty (eg anti-Palestinian demands, demands regarding foreign fighters etc); these became twelve demands. While there was no US demand for Syria to join the Abraham Accords, this was one of the five “expectations” (supposedly not “conditions”) Trump made on Sharaa when he met him in Saudi Arabia. Trump’s announcement that “all” sanctions would be lifted “immediately” therefore appeared a Syrian victory against this edifice of “conditions.”

However, while some sanctions were promptly removed, the most devastating, the Caesar sanctions, must go through Congress. Some leaders, including State Secretary Marco Rubio, right-wing Senator Lindsay Graham, and Trump’s far-right ‘counterterrorism’ tsar Sebastian Gorka, immediately began softening expectations, re-emphasising ‘conditionality’. While new trade and investment deals have continued slowly, the momentum has slowed. This post-May regime – part sanctions relief/economic engagement, part ongoing sanctions/conditionality – is the new form of US pressure in its ‘scissors’ partnership with Israeli aggression. Trump spelled it out in July: “the Secretary of State will reimpose sanctions on Syria if it’s determined that the conditions for lifting them are no longer met.”

Phase 3: July onwards – renewed US caution

A new turn began after the mid-July Suweida catastrophe. The Sharaa government bears primary responsibility – its attempt to use a local crisis to impose a military solution on the issue of decentralised governance for Druze-majority Suweida turned into a horrific massacre of the Druze. Beat back by the Druze militia, but also large-scale Israeli bombing, the government has now lost control of Suweida, and without a radical change in policy, this component of Syrian society is lost. I have discussed these events here. However, the government’s role must be separated from the use of these events by the US or Israel to intensify pressure.

In the debate between the Sharaa government advocating a relatively centralised state versus the Kurdish/SDF, Druze and Alawite preference for a decentralised or ‘federal’ system, US Syrian envoy, Tom Barrack, rejected federalism, lauded Sharaa’s “incredible enthusiasm” for integration while chiding SDF “slowness,” and stressed the only road “is through Damascus.” Aside from the arrogance of assuming the right to decree Syria’s internal system in relation to these delicate matters, his stance was odd in its 180-degree contrast with that of Israel.

This could be because Barrack is close to Erdogan and therefore less close to Israel; or it could simply be that Barrack, a Trump-lite real estate agent whose understands politics as ‘dealing’, was too clueless to understand his statements lacked nuance; or even that he set a trap for Sharaa in coordination with Israel. If the second case, Sharaa’s government remains at fault for assuming Barrack was smart, and going into Suweida like a bull in a china-shop assuming US support; if the third, falling into a trap set by a B-grade Trump clone demonstrates the government’s gullibility.

The upshot was a loss of US confidence in Sharaa. While continuing to insist there was “no Plan B” to Sharaa, Barrack now urged him to “embrace a more inclusive approach, revisit elements of the pre-war army structure, scale back Islamist indoctrination” or risk losing international support and internal fragmentation, and to “grow up as a president.” He now claimed that while Syria does not need full federalism, it needs “something close to it,” that “allows everyone to preserve their unity, culture, and language, without any threat from political Islam.” “Does [Syria] end up being decentralized? Probably. But we’re not dictating any of that,” he repeated. Messages that would have been better given before July. While pushing Trump’s desire for a ‘security agreement’ with Israel, he now recognised Sharaa would never sign the Abraham Accords because he is backed by “Sunni fundamentalists.” For the US to remove Syria from its terrorism listing would require significant changes to Syria’s political stances, he said.

Rubio (rightly) condemned the “slaughter of innocent people” during the “horrific episode” in Suweida, demanding the government “prevent ISIS and other violent jihadists from entering the area and carrying out massacres” and “hold accountable and bring to justice anyone guilty of atrocities including those in their own ranks.” The “US Central Command quietly paused its drawdown” of US troops “over concerns about the country’s ability to hold together.”

Barrack now praised the SDF in late July, as he and US CENTCOM leader Admiral Brad Cooper met SDF leaders throughout the next few months. Barrack began advocating a ‘hybrid’ approach, one US proposal seeing “parts of the SDF integrated into Syria’s new military while preserving some Kurdish forces under Mazloum Abdi.” Cooper reaffirmed the anti-ISIS partnership with the SDF, underscored by the approval in the new US Defence budget of $130 million to the anti-ISIS fight, mostly to the SDF, the US sending significant new military reinforcements to northeast Syria in late October. SDF leader Ilham Ahmed confirmed that Barrack and the US were now far more “constructive.”

New moves were made in the US Congress to condition lifting the sanctions. In July, a House committee voted to support Republican Congressman Mike Lawler bill extending sanctions for two years with conditions, including protecting minorities. More significantly, Senator Lindsay Graham moved an amendment to the 2026 defence bill allowing ‘suspension’ of sanctions based on Syria’s compliance with “a detailed set of benchmarks on security, human rights, and regional relations – particularly with Israel,” including “guaranteeing the rights of religious and ethnic minorities with representation in government institutions … maintaining peaceful relations with neighbouring states including Israel, taking decisive measures against actors deemed to threaten regional security,” removing foreign fighters from security and military institutions and not financing “terrorist” groups. According to the Syria Emergency Task Force, Graham’s Amendment 3889 adds six new requirements not even imposed “during the Assad regime’s worst atrocities.”

However, reflecting the opposing pressure to open Syria for investment, the Senate passed an amendment in October to fully repeal the Caesar Act with the passing of the defence bill; but Graham’s draconian amendment was also accepted, requiring the president to certify every six months that the Syrian government has met the conditions. If conditions are not met for two consecutive periods, sanctions should be reimposed “and remain in effect until the President or his designee makes an affirmative certification.”

While much was made of Sharaa being the first Syrian leader to address the UN in decades, the Syrian team were only given a visa from September 21-25, covering only three days of the General Assembly which ran for seven days (September 23-29). Sharaa’s statement there that “the world must not be complicit again in the killing of the Syrian people by slowing down or preventing the lifting of sanctions” – which can only be aimed at the US – indicated the continuing elusiveness of the goal.

Following government-SDF clashes in October, US military helicopters brought Abdi to Damascus on October 7 to meet with Sharaa, Barrack and Cooper, and a ceasefire was signed. A mechanism was agreed upon to integrate the SDF into the Syrian military, a compromise between the two previous positions: the SDF would neither join “as a block,” but nor as “individuals;” SDF forces “will join as large military formations formed according to the rules of the Defense Ministry,” by forming some new corps in the region; the Kurdish ‘Asiyah’ security would undergo a similar process with Syrian public security. The idea of AANES officials gaining ministries and of Abdi being appointed to a high-level military post was floated. Government media reported that integrating northeast Syria would begin with (Arab-majority) Deir ez Zour. The timing of these announcements – around October 10 – coincides closely with the US Senate vote to repeal sanctions.

Phase 4: Sharaa’s November meeting with Trump and the end of sanctions

Sharaa’s high-profile meeting with Trump in the White House on November 10 may have marked a swing back to better relations, though the actual outcomes remain to be seen. Trump’s sudden invite to Sharaa followed hot on the heels of Sharaa’s meeting with Putin in Moscow, and Shaibani’s announcement of his “early November” trip to Beijing – a timing upstaged by Trump’s invite. Almost as if the three superpowers were competing over impoverished Syria! Syria’s strategic location, the power of the Syrian revolution and the wide internal legitimacy of the Syrian government have combined with the government’s global ‘balance’ policy and deft diplomatic skills, to lead to this strange situation.

Sharaa’s US visit was contradictory. On the one hand, there was none of the public pomp, Sharaa arriving at the White House “without the customary protocol usually afforded to visiting foreign leaders, entering through a side entrance out of reporters’ view rather than the main West Wing door where cameras are usually positioned;” on the other, he was the first Syrian leader visiting the US government since 1946, and following the secret meeting, we were treated to sickening displays of Sharaa and Trump almost slobbering over each other, giving gifts and the like. But aside from the show, and our feelings of disgust, what is this really about? Quite simply, alone in the world, the US government holds two keys: that of ending its crippling sanctions, and that of somewhat restraining Israel. There is nothing more important to Syria.

On Israel, nothing was resolved, but Trump’s hosting of Sharaa, and the mere suggestion that the US may prefer a less aggressive Israel, has led to stepped up Israeli aggression (such as the November 28 slaughter of 13 civilians during the IDF raid on Beit Jinn), a further hardening of Israel’s conditions (declaring that negotiating the ‘security agreement’ is at a dead end), a provocative visit by Netanyahu and his top officials to occupied Quneitra, and even suggestions that the IDF “is considering launching a large-scale operation against President Ahmad al-Sharaa’s regime, if it discovers that any of his men were involved in the clashes” in Beit Jinn.

Next, the meeting led to Syria formally joining the 90-country Global Coalition to Defeat the Islamic State; given that this war takes place on Syrian territory, it is probably a good thing, though the Information Ministry stressed the agreement “does not yet include any military components.” Nevertheless, Syrian security forces seized the moment to demonstrate their mantle, launching a massive operation targeting ISIS cells on November 8-9, with 61 raids across multiple provinces, arresting 71 suspects. While dramatic, the Syrian government has already been fighting ISIS throughout the year (as did HTS and all rebel groups for the last decade); but the Syrian presidency officially denied media reports alleging that HTS had cooperated with the U.S.-led coalition against ISIS or al-Qaeda since 2016, calling the claims “untrue and baseless,” noting that “all decisions and measures taken at that time were made independently and internally, without coordination or requests from any external party.” Given heavy US bombing of HTS in 2016-17 by both Obama and Trump, this rings true. The foreign ministry also earlier denied reports that a US base was being set up in Damascus to promote the ‘security agreement’ with Israel; baseless media speculation about Syria has enjoyed a very full year.

Another crucial issue discussed was the ongoing integration negotiations with the SDF. According to the statement released about the meeting, “the two sides agreed to proceed with implementing the March 10 agreement signed between President Ahmad al-Sharaa and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi” (while it notes only “the American side” affirmed its support for reaching a security agreement with Israel). SDF leader Mazloum Abdi thanked Trump for taking leadership of the Syrian file and affirmed the SDF was committed to accelerating the integration process. The SDF named three commanders to assume posts in the Defence Ministry once agreement is reached, claiming it will be integrated into the Syrian military through one division and at least two brigades. While some government supporters want to believe that Trump gave them the green light to incorporate SDF/AANES on its own terms, the SDF reaction suggests on the contrary that the US wants a compromise position. Likewise, the SDF has welcomed the Syrian government’s accession to the anti-ISIS coalition, seeing it as more a chance to collaborate, rather than as competition for US favour; it figures the US will not want two members of its anti-ISIS front warring with each other.

The meeting with Sharaa did not end the sanctions, only leading to a further 6-month suspension, but the amendment to the defence bill lifting them did finally pass the House in mid-December, despite Israel campaigning in Congress to maintain sanctions. In announcing the suspension, Rubio made clear that the US “expects to see tangible steps by the Syrian government to turn the page on the past and work toward peace in the region;” and the amendment itself includes the Graham amendment with its 8 demands that the president must regularly report progress on the next four years:

- Taking concrete and verifiable steps to combat ISIS, al-Qaeda and “other terrorist groups” in coordination with the US

- Removing foreign fighters from senior positions in government, state and security apparatus

- Respecting rights of religious and ethnic minorities and ensuring their equitable representation in government and parliament

- No “unilateral or unprovoked” military action against neighbours, “including Israel” (note: the US considers Syria’s Golan Heights to be “Israel”)

- Implementing the integration agreement with the SDF, including integration of security forces and political representation

- Combatting money-laundering, “terrorism-financing”, weapons of mass destruction, and “ceasing support for sanctioned groups or individuals, including terrorist organisations, that threaten US or allied national security”

- Prosecting perpetrators of gross human rights abuses since December 8, 2024, especially during attacks in religious minorities

- Verifiable action against production and trafficking of drugs, especially Captagon

If the president cannot show “positive certification” in two consecutive reports, sanctions may be reimposed. To drive the point home, a few days later a group of 136 House Republicans (more than half of their total) released a joint statement calling for increased oversight of and accountability from Syria, stressing that the provision for ‘snapback’ sanctions must be imposed if necessary, and condemning the “mass murder of the Syrian Christians, Druze, Alawites, Kurds, and other religious and ethnic minorities.”

Notably, Trump’s signing of the end of the Caesar Act was followed closely by his inclusion of Syria and Palestine as countries whose nationals are barred from entering the US (they had not been on his original list last month), and Barrack’s meeting with Netanyahu in which they “reached understandings” that Israel had “freedom of operation” inside Syria, despite Barrack still incongruously calling for a “security agreement.” Trump also yet again boasted that he had ”signed the Golan Heights over to Israel” and that it is worth “trillions of dollars.”

The twists and turns of US policy indicate a comprehensive lack of principle. Despite the public expressions of friendship (especially Trump’s clownish demeanour and fawning over Sharaa’s “attractiveness”), neither side trusts the other, but understands the pragmatic reality. The US needs some kind of integration of the Syrian state and a degree of stability so that its Arab and Turkish allies can invest, and to continue the war against ISIS (and Europe needs some stability to send back refugees); Syria knows only the US can end sanctions and perhaps pressure Israel to calm its aggression. However, US refusal to issue a single condemnation of this aggression and Trump’s doubling down on its support for Israel’s Golan theft indicate that the US only wants this integrated state as a vassal.

Concluding remarks: Where concessions go too far

This review has explained Syrian foreign policy from the perspective that it is a devastated country under foreign occupation, aggression and embargo, and thereby understand it without necessarily ‘endorsing’ or ‘condemning’. Socialists may well understand that capitalist governments will undertake a ‘pro-capitalist foreign policy’, but apart from there being no ‘non-capitalist’ countries in the world to connect with – making the statement an irrelevant truism – it is also worth considering how differently a ‘socialist’ Syria would act in similar circumstances. Leaving aside the great betrayals that the Stalinist USSR and Maoist China were guilty of, even governments that non-Stalinist socialists are often more favourable to – such as early post-revolution, pre-Stalin Russia/USSR or Cuba since the 1960s – have been forced by reality to make serious foreign policy compromises with alleged ‘principles’.

Arguably, the Syrian government often says and does things to curry favour with imperialist or reactionary states that have surpassed what could be considered necessary, thereby damaging its reputation (and that of the Syrian revolution) and its standing in front of the region’s peoples (as opposed to its rulers). While a socialist or even a revolutionary democratic government in the spirit of 2011 may be more conscious about not alienating the popular forces in the region while making necessary compromises, a bourgeois government would have fewer qualms.

One example is Sharaa’s offer to build a ‘Trump Tower’ in Damascus, while pleading to get the sanctions lifted before his meeting in Riyadh in May. While the objective is desperately important, the pressure was already there from Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey, and sections of the US Congress and US capital; a ‘Trump tower’ in the context of Trump’s support for the Gaza genocide would be unnecessary, damaging excess.