By Michael Karadjis

The agreement between the Syrian government and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) on January 30 brings about the integration of the SDF and the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES) into the Syrian state’s institutions. However, it contains a number of aspects which allow a degree of continued self-rule in the Kurdish regions:

- For example, on the main issue which had divided the two sides since the March 10 integration agreement – whether the SDF military would integrate into the Syrian army on an “individual” basis or as a “bloc” – the outcome comes closer to the latter even if formally the former, in that a new army division, consisting of three brigades, will be created for the SDF to collectively ‘integrate into’ in Hasakah governate, while a new brigade for the SDF in Kobani will become part of the Aleppo military division.

- The Kurdish Asayish internal security forces will be re-badged as part of Syrian public security, while continuing to patrol Kobani and Kurdish regions in Hasakah.

- The Syrian army will not enter any “Kurdish areas,” or any “cities and towns” in Hasakah at all.

- The SDF is to appoint the governor of Hasakah governate, the deputy Defence Minister and a number of other high posts, as well as select representatives from Hasakah and Kobani for the People’s Assembly, which had been left vacant last year.

While the civilian institutions of DAANES will be integrated into Syrian institutions, a number of provisions also imply some degree of ‘re-badging’ while maintaining the essence of the ‘autonomous administration’:

- “settlement and certification of all school, university, and institute certificates issued by the Autonomous Administration”

- “licensing of all local and cultural organizations and media institutions” (in accordance with relevant laws)

- “working with the Ministry of Education to discuss the educational pathway of the Kurdish community and to take educational particularities into account.”

Together with references to “protecting the particular character of Kurdish areas” in the earlier January 18 agreement, these items suggest that the degree of effective local decision-making, including the retention of the more progressive aspects of the Rojava project, could well be questions of interpretation and negotiation, rather than a flat suppression as more negative readings could suggest. Certainly, the more positive interpretation is being given by leading SDF and AANES figures such as Mazloum Abdi.

The agreement also called for facilitating the return of all displaced Kurds to Afrin and Sere Kaniye (Ras al-Ain). While a positive statement, this is currently made difficult in Afrin, and impossible in Sere Kaniye, by the presence of re-badged former Syrian National Army (SNA) brigades who committed atrocities against Kurds and plundered their properties when they took part in the Turkish invasions of 2018 and 2019 respectively (when hundreds of thousands of Kurds were driven out), as well as some remaining Turkish troops. However, SDF leaders have claimed that Turkish troops have now left Afrin (and, hopefully, will also be leaving the strip they control in the northeast around Sere Kaniye), while well-informed Syria watcher Charles Lister claims that “former SNA opposition fighters in Ras al-Ayn and Afrin will be replaced by other MOD units.” While Afrin Kurds still suffer harassment by ex-SNA brigades, the situation has improved significantly since the new government came to power and began pushing these brigades aside and working towards restitution of the Kurds’ property; some 70,000 Kurds returned to Afrin in the first months after the revolution, though many more still languish elsewhere in camps. Meanwhile, all three Afrin positions for the People’s Council were won by Kurds, “including Dr. Rankin Abdo, a female doctor and activist whose public views on Ahmed al-Sharaa are far from positive.”

To all this must be added the January 16 presidential decree on Kurdish rights, which declared the Kurds an essential component of Syria, declared Kurdish to be a “national language” that can be taught in schools, made the Kurdish Newroz festival a national holiday, banned hate-speech against Kurds, and annulled the results of the botched 1962 census which had stripped some 20 percent of Syrian Kurds of their citizenship; hundreds of thousands of Kurds were at a stroke granted citizenship.

Taken as a whole, all of the above represents a picture that is so comprehensively superior to anything during the 60-year Baathist dictatorship or before regarding the Syrian Kurdish issue that it is simply night and day. I think this at least should be conceded by critics before moving on; getting this far is an accomplishment that would have been impossible without the Syrian revolution, in the broadest sense of the term.

However, for supporters of the Rojava revolution, that is hardly the point: during those revolutionary years, they made their own revolution, they contend, so the current agreement integrating the Autonomous Administration into the Syrian state is a setback – not from the Baathist past, but from what they achieved in the meantime. There may be lots of formal rights now, but it is a step back from their autonomy, from Kurdish self-determination, and from the independent decision-making of the Rojava project they launched, with its range of radical policies from women’s empowerment through civil marriage to communal decision-making “taken closer to the ground” or even “the reformation of the legal system with an emphasis on restorative justice,” and many more claimed – though also often strongly disputed – achievements. While reality has been combined with much hype and uncritical adulation, and denial of its many serious faults, it would be difficult to not recognise the achievements in the gender equality area for example (leaving aside the tendency of such articles to give an incomplete picture of the reality in the rest of Syria).

An example of this critique which sees little positive in the current situation comes from Turkish revolutionary Marxist Foti Benisloy, who claims the situation under the current Syrian government “relegates the Kurds – at best – to a minority that will enjoy certain cultural rights on an individual level … The presidential decree published on 17 January, which recognizes certain rights of identity for Kurds, clearly shows that the Kurdish issue in Syria is not treated as a matter of self-government and self-determination, but as a mere problem of minority rights.”

Now, one can argue that a more explicit recognition of Kurdish autonomy in the areas they form a majority would be preferable to the agreement as is; even the most positive spin on the agreement’s terms regarding effective Kurdish self-rule is that this remains a matter of interpretation and negotiation, so there is no guarantee that this will eventuate.

However, we should remember that the SDF leadership, from very soon after the overthrow of Assad, declared its desire to ‘integrate’ into the new Syria and signed the March integration agreement, because they recognised that it was impossible to continue to have two governments in Syria, especially as the one they ran in 30 percent of Syria in the northeast extended far beyond the Kurdish regions; one way or another integration was necessary. Perhaps what they did not realise then was how shaky their hold was over the vast Arab majority of the DAANES statelet; negotiating as if all of this was “theirs,” which just happened to cover nearly all of Syria’s sovereign oil wealth, was a huge error of judgement. But once we take these regions away – and of course, they simply ‘fell away’ in January as the Arab masses shrugged off Kurdish-led SDF rule – this brings the issue back from an expanded imaginary ‘multi-ethnic Rojava’ concept to the Kurdish heartlands, and hence to the issue of Kurdish self-rule.

But that’s where a new problem arises: how do we define ‘autonomy’ or ‘self-determination’ given the demographic and geographic reality of ‘Syrian Kurdistan’. This essay will look at this question through a series of maps, and then wind up citing some recent comments by none other than the father of the ‘Rojava’ project, Turkey’s long-time Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan, and how this bears on the discussion.

Maps of Syrian Kurdish demography

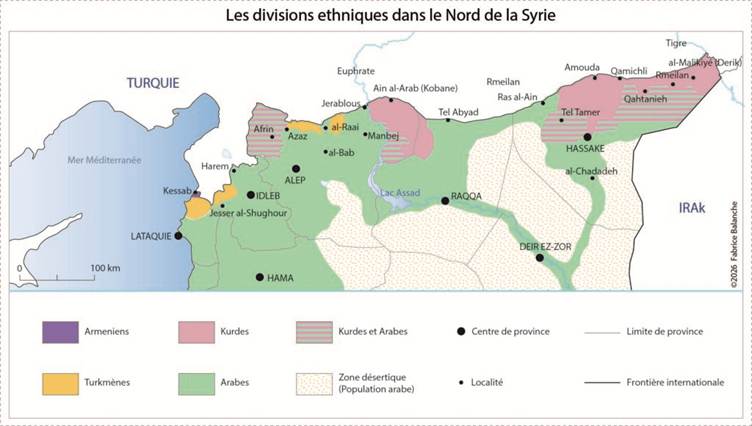

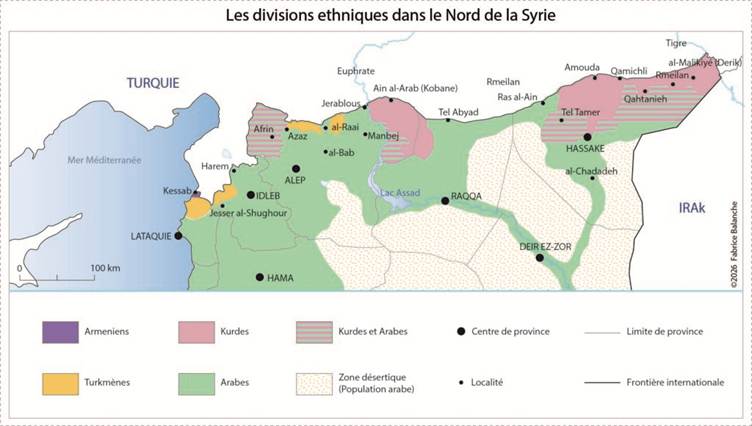

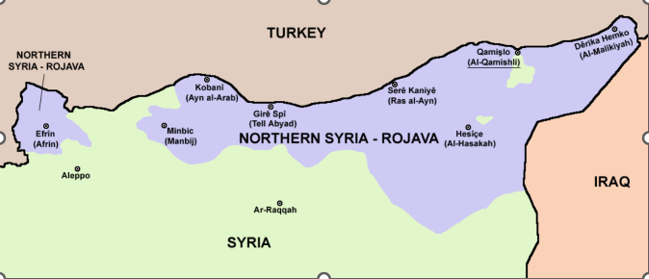

The first map shows the demographic reality of Syria:

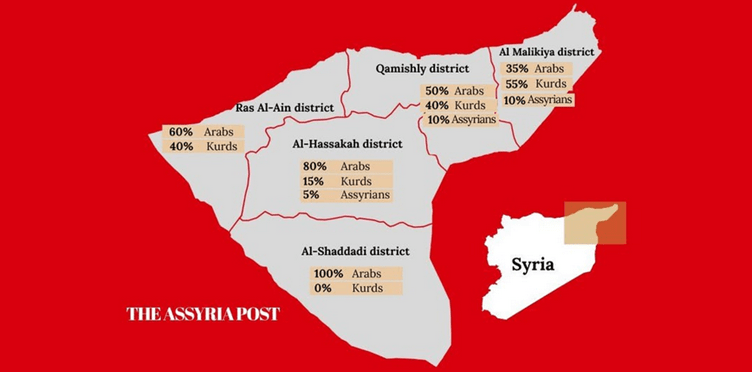

Figure 1: Ethnic composition of northern Syria

Focusing on the north of the map, the pinkish areas show the main concentrations of Kurdish population. Two things are immediately apparent – first, the lack of any geographic contiguity, their wide separation into the three main concentrations – the town of Afrin the northwest, the town of Kobani in the centre-west (both belong to Aleppo governate), and Hasakah governate in the northeast; and second, even in the largest area of Kurdish population, the northeast ‘nose’ of Hasakah, Kurds are very interspersed with other groups.

This can be shown even more starkly if we look at medium-sized urban centres, of which only six in Syria, scattered along the Turkish border, are majority Kurdish: Afrin, Kobani, Darbasiyeh, Amude, Qamishli and Derik (Malikiyah):

Figure 2: Major urban centres with majority Kurdish population.

As we can see, the first two are distant form each other and even more distant from the other four in Hasakah governate, which are reasonably close to each other; these four Hasakah towns have Arab, Assyrian and Armenian minorities.

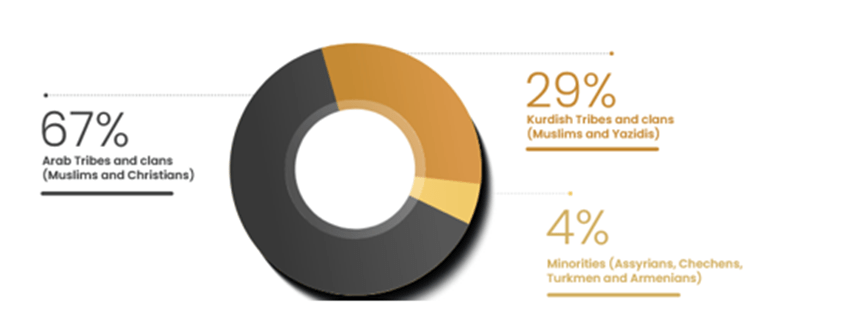

Despite common misconceptions, neither Hasakah governate as a whole, nor most of its districts, nor its capital Hasakah city, are Kurdish majority. Hasakah governate is majority Arab, but its 30 percent Kurdish population is the largest of any governate in Syria (apologies for the language of “tribes and clans” in the graphic):

Figure 3: Ethnic composition of Hasakah governate

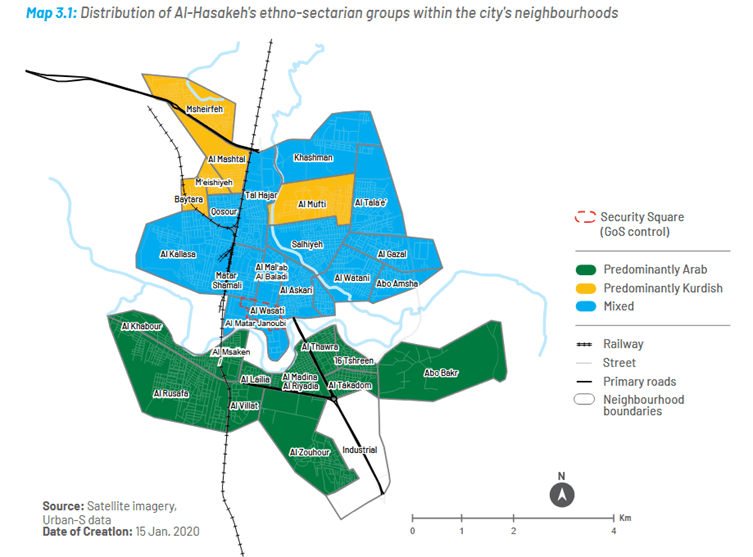

Hasakah city has a large Kurdish minority (42 percent), the majority mostly Arab with a small population of Assyrians. But there is a clear geographic separation, the Arab population predominantly living in the southern neighbourhoods, Kurds in the north, while the central neighbourhoods have mixed populations:

Figure 4: Ethnic composition of Hasakah city

This preponderance of Arabs in the south of the city borders directly on the almost complete Arab majority in the south of the governate, the city located at the crossing point between the Arab south and the more Kurdish and mixed north of Hasakah governate:

Figure 5: Ethnic composition of the five districts of Hasakah governate

This map shows that southern Hasakah governate, the district of Al-Shaddadi, is almost entirely Arab-populated, bordering on the Arab-populated Deir-Ezzor governate, which recently shrugged off SDF rule, along with Arab-populated Raqqa governate, so it is not surprising that this district, up to the gates of Hasakah city, also rapidly fell to the Syrian government in January.

According to this map, the central Al-Hasakah district itself also has a large Arab majority, much larger than the city itself; and another two districts, Rais al-Ain and Qamishli, also have Arab pluralities or slight majorities, with Kurds accounting for a very large 40 percent of the population in each, the latter also with 10 percent Assyrians; but as we saw above, a number of main urban centres in these districts are majority Kurdish. So, if this data is more or less right, the only district of Hasakah governate with an absolute Kurdish majority is the eastern-most Al-Malikiya, with 55 percent Kurds, 10 percent Assyrians and the remainder Arabs.

A note of caution, however – I have used this map indicatively, as it came to my attention without having time for further research, and would be happy for any of it to be corrected; the main point, however, is that both the south-north, Arab-Kurd distinction, and the ethnic mix in most regions, are well-established. But I do not necessarily trust the actual figures: an important issue is the 1962 census that removed the citizenship of one fifth of the Kurdish population – which the current government has just annulled with its presidential decree on Kurdish rights. I cannot know if these figures, even if nominally correct, include these “non-citizen” Kurds who have now become citizens. If this data does not include these Kurds, their inclusion could well tip the balance in the northern districts to absolute Kurdish majority, while also boosting their numbers in Hasakah district.

Either way, Hasakah city itself is a kind of demographic ‘border’ between a very Arab south and a very mixed or Kurdish north of the governate, which may also relate to political views towards the DAANES/Rojava project.

How then does the above demographic reality relate to questions of Kurdish autonomy, and to the various actual Rojava/DAANES statelets that have arisen since 2012?

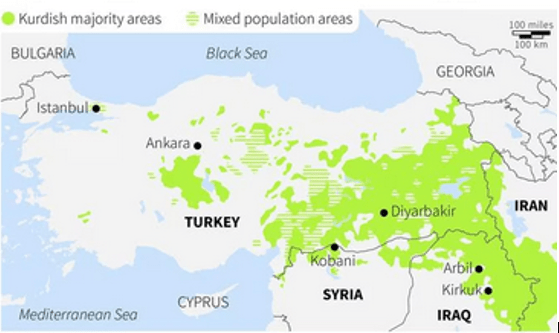

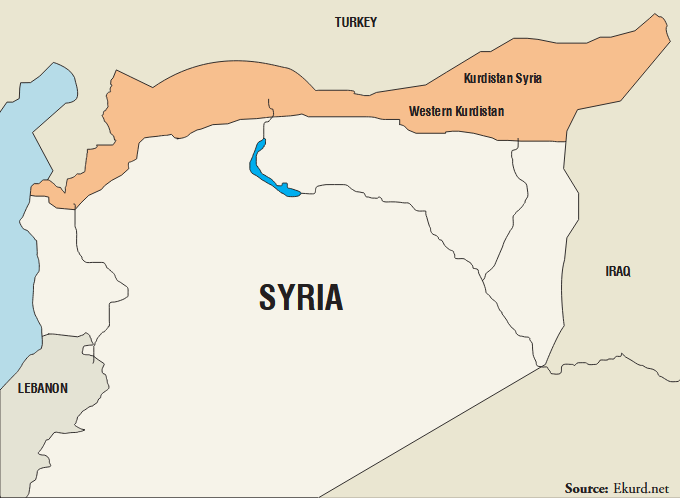

First let’s see how different the Syrian situation is to that of Kurds in Turkey, Iran and Iraq:

Figure 6: Kurdish populated regions of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

What is clear is that in these three countries, there are large regions of contiguous Kurdish population, in sharp contrast to Syria. This is the basis of the idea of that the Kurds, as a nation in every sense of the term, should be entitled to their own nation-state, as the Turkey-based Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) fought for in the 1980s and 1990s. The dominant Kurdish movements in Iran and Iraq did not advocate such a state, but rather a high level of territorial autonomy within those states (like what now exists in Iraq), but once again this was realistic given this demographic reality, in sharp contrast to Syria – there is no contiguous region for territorial autonomy, so ‘autonomy’ can only really mean the degree of Kurdish self-rule at the local level.

The map also explains to us why the Syrian Kurds are so widely separated: the three main concentrations are ‘fingers’ of Kurdish population from Turkey or Iraq stretching into Syria. Only if an independent Kurdish nation-state were to be established across the whole region could these small concentrations of Syrian Kurds viably join it. Yet even the PKK long ago gave up the nation-state idea.

So how does this reality relate to the various sizes and shapes of the statelets ruled by the PYD/YPG/SDF since 2012?

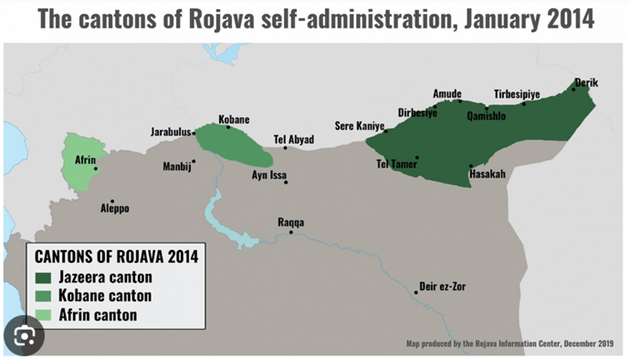

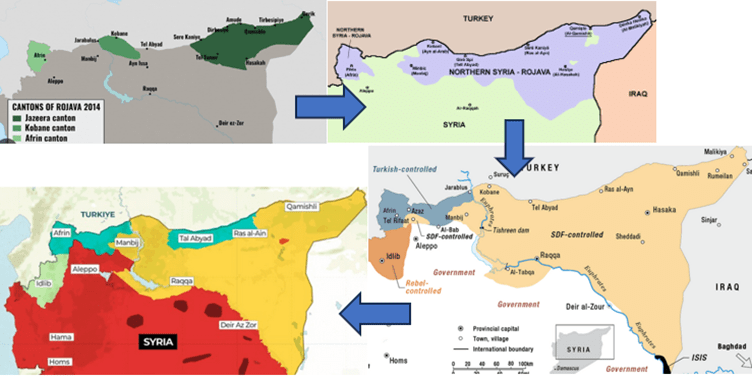

The original three ‘Rojava’ cantons were established in 2012 by the Kurdish Peoples Protection Units (YPG), the armed wing of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the Syrian branch of the PKK. We can see these cantons corresponded reasonably closely to the main concentrations of Kurdish population, as we saw in Figure 1 above. This is only natural; in the chaos of revolution, counterrevolution and civil conflict, a Kurdish armed militia gained control of Kurdish population centres, the regions where they would have some base. Now, the story is not that simple, because many Kurds throughout the north were also supporting the PYD’s rivals in the Kurdish National Council (KNC), who were taking part in anti-Assad protests alongside other Syrians throughout 2011-2012; the impact of the PYD setting up Kurdish cantons arguably cut the Kurds off from the joint democratic struggle. Incidentally, this often involved well-documented PYD violence against Kurdish anti-Assad demonstrators; while on the other hand, explaining the drift towards armed separation must also factor in a hostile Turkish influence on parts of the Syrian opposition, and the rise of jihadist groups like Jabhat al-Nusra, which launched armed attacks on the Kurdish cantons throughout 2013. But all this is another story – simply from the point of view of Kurdish self-rule, these original cantons roughly corresponded to Kurdish populations, reproduced below again for comparison:

Figure 8: The cantons of Rojava self-administration, roughly 2012-2014

[Figure 1: Ethnic composition of northern Syria]

Yet by October 2016, the map of ‘Rojava’ already looked like this:

Figure 9: The Rojava self-administration October 2016.

Part of the reason for this change – ie the takeover of regions where Kurds did not predominate and in some cases were non-existent – was the large-scale intervention of two imperialist superpowers, the US and Russia, both allying themselves with the PYD/YPG in different parts of Syria, with their own objectives. These objectives either dovetailed with, or encouraged, a new aggressive irredentist version of the ‘Rojava’ state project the PYD/YPG was now developing; a version which in practice was the 180-degree opposite of the ideals of ‘democratic confederalism’ which the Rojava project was initially built on.

That is not to suggest there was no reality to the democratic confederalism project – much research comes up with markedly opposing opinions as to its reality, but certainly there has been enough carried out that demonstrates remarkable achievements in places. What is striking when looking back at these early reports on the Rojava revolution, however, was that they were almost invariably describing the Kurdish-majority heartlands, or otherwise some of the very ethnically mixed parts of the Hasakah region where long traditions of inter-ethnic co-existence were relatively easy to translate into a ‘democratic confederalist’ polity. But this ideal is by definition negated once the leadership decided to create an irridentist ‘Rojava’ statelet via conquest with aid of global imperialist powers.

Now admittedly it is not as simple as that. The US intervention, which began in September 2014 as the US airforce bombed ISIS to halt its genocidal advance towards Kurdish Kobani, was aimed at destroying ISIS in Syria; the YPG (later SDF) has been called the “ground troops” of the US “war on terror,” but this is not really accurate, because obviously the YPG had its own reasons for wanting to destroy ISIS. This began a decade-long US-YPG (later US-SDF) military alliance which eventually succeeded in expelling ISIS from its ‘capital’ in Raqqa – with the US airforce completely destroying Raqqa in the process – and then destroying most of the rest of the ‘Caliphate’ by 2019 (in the last year or two a Russian-backed Assad regime offensive joined in to “mop up” after the US-SDF had done all the heavy lifting – the Assadist discourse that the regime and its allies destroyed ISIS in Syria is real alternative reality stuff).

……………………………………………………………

I will just digress a little here, to correct a common meme that claims only the YPG/SDF (or sometimes “only the Kurds”) fought ISIS and “saved humanity,” a meme often used while slandering the current Syrian government as “ISIS.” A united front of all Syrian rebel groups (including Nusra, which current president al-Sharaa then led, then just one of dozens or hundreds of rebel formations) had already launched its own full-scale war on ISIS in January 2014, driving ISIS out of all of northwest Syria (Idlib, Aleppo, northern Hama and Latakia governates), even from Deir Ezzor in the east, and briefly even from Raqqa, though ISIS rallied hard and got Raqqa back. They did this with no support from the US airforce or any other, and through the entire operation, Assad’s airforce bombed the rebels, not ISIS. The rebels lost 7000 troops in this operation, a fact rarely mentioned in discussing the defeat of ISIS. ISIS took back Deir Ezzor in the east six months later after its massive haul of US weapons from its conquest of Mosul in Iraq – and as ISIS besieged rebel-held Deir Ezzor in July 2014, the Assad regime again helped it by bombing the rebels. And as the Aleppo rebels continually tried throughout 2015 to drive ISIS out of part of northeast Aleppo governate it had later reconquered (around Jarablus and Manbij), the Assad regime again continually bombed the rebels, and, though the US was by now in Syria fighting ISIS, it never bombed ISIS in support of these rebel offensives (on the contrary, the US often took time off from bombing ISIS to bomb Nusra, HTS, Ahrar al-Sham or other rebel groups).

Seeing this rebel success, the US put it to the Free Syrian Army (FSA): drop your war against Assad, and fight only ISIS, and we’ll arm you. The rebels, who were already fighting ISIS in their own interests but whose main war was against the regime, rejected this diktat, and the small flow of US light arms which had only just started to flow soon after began to dry up (when Trump was elected in 2016 he abruptly ended all arms to the rebels and ended all funding to the community councils in rebel-held regions).

Given the US wanted a partner that was fighting ISIS only, and not fighting the regime, the YPG/SDF was a perfect fit. That is not a slander; let’s say the YPG needed to prioritise due to geography (eg the US-SDF war on ISIS was in east Syria, the Assad regime versus rebels war was mostly in west Syria). Either way, it is still a fact.

……………………………………………………….

But now returning from this historical interlude, as the US-SDF alliance advanced against ISIS, naturally these regions needed someone to govern them; in war conditions, that would be the armed group defeating ISIS. So while Figure 9 above shows vast areas of non-Kurdish majority, especially southern Hasakah and the large region between Sere Kaniye and Kobani, initially this was simply rational. More on where the problems arose later.

The problem is, this US backing for territorial expansion may have been responsible for giving the PYD/YPG leadership ideas well beyond the necessary expansion against ISIS. In 2015, Polat Can, a senior PYD official, stated that “We in the YPG have a strategic goal, to link Afrin with Kobani. We will do everything we can to achieve it.” Never mind the hundreds of thousands (at least) of Arabs and Turkmen living between these two Kurdish concentrations. The PYD now had a map in its head of a grotesque ‘Rojava’ state stretching along the entire length of the northern border, regardless of ethnic realities, to be brought about by military conquest; ridiculous maps, like the one below, began to regularly appear in pro-Rojava publications.

Figure 10: Irredentist map of projected ‘Rojava’ state

The onset of Russia’s horrific air war in support of the Assad regime in September 2015 was to be their tool. The PYD welcomed the Russian intervention. While US intervention in its war against ISIS took place in eastern Syria, Russian intervention against the anti-Assad rebels took place in the west. The Afrin and Sheikh Maqsud PYD leaderships launched a large-scale attack on the rebel-held, Arab majority Tel Rifaat and surrounding region north of Aleppo in January 2016, backed by heavy bombing by the Russian airforce. They seized the region, expelling some 100,000 Arabs and Turkmen, who ended up in camps in Aziz on the Turkish border. While the PYD’s aim was to advance its irredentist project rather than to aid Assad as such (Assad always promised to crush Kurdish autonomy as soon as he regained control), for now it put the Aleppo wing of the PYD in alliance with Assad – made clearer when they actually aided Assad’s reconquest of rebel-held eastern Aleppo later in 2016.

Meanwhile, the US-SDF alliance drove ISIS from Arab-majority Manbij just west of Kobani in mid-2016, then Raqqa in 2017 and Deir Ezzor in 2018 (dividing the latter with the Assad regime forces finally coming from the west). But in the northwest, the SDF suffered a huge setback in 2018 when the Turkish army invaded Kurdish Afrin, driving out some 130,000 Kurds, who ended up, ironically, in the homes of those earlier expelled by the SDF from Tel Rifaat; and the next year, Turkey invaded part of the northeast, and seized the cities of Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain, with their substantial (though not majority) Kurdish populations, driving out some 200,000 Kurds.

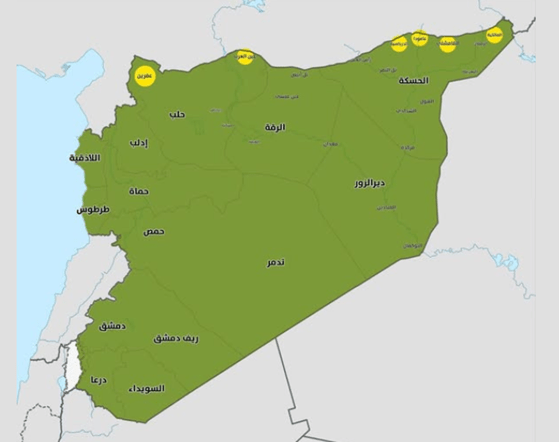

Therefore, if we look just before the fall of Assad, after both SDF expansion but also defeats, the map of the DAANES/Rojava statelet, shown in the yellow in Figure 11 below and accounting for 30 percent of Syria’s territory, bears almost no resemblance to a map of Kurdish regions in Syria:

Figure 11: Areas of control in northern Syria in December 2024: yellow is DAANES/Rojava, dark green is Turkey/Syrian National Army, light green HTS and allied rebels, red Assad regime.

Quite an evolution:

Figure 12: Rojava/DAANES statelets clockwise in 2014, 2016, 2018, 2024.

Between ‘democratic confederalism’ and negation of self-determination in Raqqa and Deir Ezzor

So, getting back to the initially justified expansion of the Rojava statelet to the Arab-populated governates of Raqqa and Deir Ezzor, due to their liberation from ISIS by the US/SDF alliance, what went wrong after that?

It is one thing to rule another people as an emergency measure, and another to stay there a decade without ceding any real authority to the people there. This of course is a topic of its own, beyond the geography/demography focus here, but is essential to understand – no matter how liberatory one considers their ideology to be, once the elementary basics of the right to self-determination are violated, ‘liberation’ is cancelled. There is a wealth of good first hand material about the Arab residents feeling like fourth-class civilians, feeling they had no power due to the ultimate control of all decision-making by the PYD, ie a Kurdish party, about the actual authoritarianism of the SDF there despite the anarchist cloak, which especially intensified in the last year following the overthrow of Assad, with the SDF banning celebrations of Assad’s overthrow, imprisoning people just for raising revolution flags or even singing pro-revolution songs and so on. The mass celebrations as the Syrian army entered these regions are unmistakable (and here and here and so many more); actually what we saw was an uprising, including the defection of virtually the entire 50,000-strong Arab component of the SDF.

One specific aspect useful to note here: when ISIS was threatening the region back in 2014, various non-Kurdish militia in the region joined forces with the YPG to fight ISIS, including for example the al-Sandidid forces of the Shammar tribe, and also the Free Syrian Army’s 11th Division, known as the Raqqa Revolutionaries Front (RRF). Once the YPG was expanded into the SDF, these other forces joined. But the treatment of the RRF by the PYD/YPG is an example of how actual self-determination was shoved aside when the Kurdish leadership was challenged. This Wikipedia page gives a good summary, backed by abundant sources. The local Raqqa revolutionaries, who had earlier fought the Assad regime, were more or less representative of the Raqqa population; they arose from there. Much more so than a Kurdish militia that covered Raqqa with images of a Kurdish leader from Turkey.

That is a story of its own; the point is that there was a contradiction between a ‘democratic confederalist’ project which by definition is not about territorial conquest, and the long-term rule by the SDF, dominated by a Kurdish party, over another people, to the point that discussions about ‘autonomy’ and ‘federalism’ throughout 2025 seemed to assume that the entire 30 percent of Syria ruled by the SDF, with its arbitrary borders, should be the basis of some kind of autonomy or federal unit. Oddly for a project that aims to go beyond the prison of the arbitrary borders of modern states, the rupture of the arbitrary borders of DAANES by an act of Arab self-determination, as the Arab region collapsed into the more natural hands of the Syrian government, has been widely interpreted as a massive violation of Kurdish autonomy!

Ocalan: It “has nothing to do with federal autonomy”

Now that that phase is over, we return to the start: the regions the Syrian army did not march into are regions either of Kurdish majority or of large Kurdish concentrations mixed with other groups. But as we saw at the start, even these regions are not contiguous, and even the largest region of Kurdish concentration, Hasakah governate, is neither Kurdish majority as a whole, and even the Kurdish majority cities, towns and regions are interspersed with non-Kurdish regions. Just what can ‘Kurdish autonomy’, or Kurdish self-determination, in any territorial sense, mean then?

Ironically, while some Kurds and their supporters abroad now insist that some kind of autonomy must be maintained, and that anything less is betrayal, it is interesting to cite Ocalan himself, the Rojava project’s key inspiration. In a recent meeting between Öcalan and a commission of the Turkish parliament, he explained that the Kurds should find their place “through democratic self‑organisation within the existing framework” (whether in Turkey or in Syria); not only did this have nothing to do with secession, but it also “has nothing to do with federal autonomy.” In fact, he argued that a state needs both “central unitary powers and regional local democracy,” and that one cannot exist without the other. Far from ‘federalism’, this is an argument for a central state with decentralised power at the local level.

Of course, for those well-versed in Ocalan thought, this comes as no surprise; the very fact that peoples live interspersed and that there are few regions of homogenous ethnic population means that ‘democratic confederalism’ provides a better basis for minority groups to have their rights than territorial autonomy as such, let alone secession. What this means is that enhanced local ‘autonomy’ is needed, in the sense that local populations, of whatever ethnicity, should have wide-ranging powers over their own political, cultural, education, security and other affairs, while not contradicting the necessity of overriding central powers.

If we look at the current SDF-Government agreement of January 30, while far from ideal in many respects, there are arguably aspects of this that could be built on – or at least, there are many articles of the agreement expressed in a general enough way to be open to interpretation, subject to negotiations of what ‘integration’ means in practice. This is the way a number of prominent SDF/DAANES leaders are interpreting it. For example, Mazloum Abdi claims “the institutions that the Autonomous Administration was managing will remain as they are,” Ilham Ahmed claims the co-chair system will remain, that the YPJ will be included in the new brigades formed for the SDF, and that “education will be reorganized in a way that preserves Kurdish as an official language of instruction,” Fawza Youssef adding that “educational institutions will retain their specific character, with joint committees to be formed to discuss the continuity of the educational process, including curricula and languages of instruction,” while Sipan Hemo claims that “everything—from command structure to deployment centers—has been determined by us,” and that not only the Hasakah governor, but all district governors in Hasakah will be appointed by the SDF.

Indeed, Ocalan appears to be close to Abdi and was likely an important influence on his pragmatic approach that led to the agreement. As an aside, he also claims that “Israel today needs a Kurdish state as a geopolitical pillar for lasting dominance in the Middle East” but he sees the future of the Kurds tied to the peoples around them; earlier in 2025, rejecting Israeli dominance through the Kurds, he claimed to be the person who could prevent the SDF from falling under Israeli influence; his messages to the SDF were strongly pro-integration.

As for president al-Sharaa, he has regularly stressed that “even the concept of federalism, which some are putting forward, does not differ in substance from the local administration framework in force in Syria, particularly Law No. 107 issued more than ten years ago, which in practice already incorporates many of the concepts being proposed today, with the possibility of introducing amendments to it”.

So, could these various threads – SDF leaders interpretations of the agreement, mention of the ‘special character of the Kurdish regions’ in the agreement, Ocalan’s interpretation of ‘democratic confederalism’, Sharaa’s claims about the local administration law, the government’s new decree on Kurdish rights – mean that Kurdish autonomy at the local level, and the best aspects of ‘Rojava’ policy, could survive in the new integrated framework?

Here, we can be hopeful without needing to have illusions or to make confident predictions about the future. Everything depends on struggle, on negotiation, on relationship of forces. After all, as Sharaa notes, the legislation he points to was enacted under Assad (in 2011); he obviously does not think it was ever a reality under the Baath. The Kurdish leadership’s attempt to negotiate as wide self-rule as possible within the integrated framework should not be criticised as some secret desire for ‘separatism’, as many government supporters do – apart from local self-rule being a good thing in its own right, there are two important reasons why this is especially important for the Kurds.

First, the Kurds are an historically oppressed people in Syria and the region, as al-Sharaa’s decree on Kurdish rights clearly recognises. Historical oppression cannot be overcome simply by laws and decrees, but by long-term empowerment and redress of historical injustice.

Second, the assumption that merely integrating into the Syrian state with a set of Kurdish rights laws automatically leads to equality ignores the fact that the new Syrian polity itself, after decades of brutally oppressive Baath rule, can at this stage hardly be called either democratic, or representative of all components of Syrian society. To the contrary, at both the political and military-security level, it remains largely a state of the Arab-Sunni majority – whether one views that as the government’s ‘intention’ or rather an inheritance to be overcome. It is largely an inheritance from the Baathist catastrophe – Baathist rule was always based on effective sectarian division, with control of the military-security apparatus solidly in the hands of the Alawite minority, but one large dimension of its violent counterrevolution after 2011 was a war of sectarian genocide against the Sunni majority which formed the main – but not exclusive – base of the revolution; this utterly destroyed the social fabric of Syrian society. Some claim the new government is making slow attempts to overcome this; others claim the new ruling elite inevitably seeks to utilise a soft Sunni sectarianism as its ideological prop in the reestablishment of a soft-authoritarian capitalist rule.

While this is too complex an issue to go into detail here, the widely-noted ‘one-colour’ nature of the state to date, despite some improvement throughout the year, means that it requires maximum democratic change to become a genuinely inclusive polity – and given this, it is not just understandable, but essential, that non-Arab Sunni components – Alawites, Druze, Christians, Kurds etc – are able to represent themselves in a genuine process of democratic integration, regardless of who their current leaderships are. Chances to begin such a process – such as the National Dialogue Conference early in 2025, or the indirect ‘election’ process of the People’s Assembly later in the year – were either farcical in the first case, or failed to advance this process in the second. According to Ocalan, “Ahmed al‑Sharaa must, like the SDF, take concrete positive steps toward a democratic Syria,” his “central recommendation for Syria [being] to establish local democracy.”

The government has just accepted the SDF’s nomination of long-time SDF leader Nour al-Din Ahmad as Governor of Hasakah governate; the SDF has put forward another 10 names for positions, include deputy Minister of Defence. The SDF will also nominate people to represent Hasakah and Kobani in the People’s Assembly (places were left vacant during the ‘election’ process). On February 4, while meeting a delegation from the (non-PYD) Kurdish National Council in Syria in Damascus, al-Sharaa stressed his commitment to guaranteeing Kurdish rights within the constitution. When Colonel Mohammad Abdul Ghani, commander of Internal Security in Aleppo Governorate, visited Kobani to prepare for the entry of security forces to begin integrating the SDF’s Asayish forces, who will continue to be the (re-badged) local security force, he used the name “Kobani” rather than its Arabic name, Ain al-Arab. The entry of internal security into Hasakah and Qamishli for the same purposes proceeded smoothly; the joint statement by the Asayish and MoI leaderships, led off by a female YPJ cadre, has a genuine feeling to it; Interior Ministry spokesperson Nour al-Din al-Baba thanked the local Kurds for their “warm welcome” and “love and gratitude.” These are positive signs; of course, there is no guarantee of what will happen tomorrow.

Ironically, the worst thing that happened during those days was that the SDF arrested dozens of Hasakah locals for coming out to welcome the entry of state security forces. A reminder for those decrying the end of ‘radical democracy’ at the hands of a ‘jihadist’ regime that authoritarian practices are not restricted to one side. Indeed, one issue raised by some Kurds opposed to the PYD is that the agreement at state level between the government and SDF may leave unresolved the issue of the democratic rights of Kurdish oppositionists in the SDF-controlled region.

On the other hand, despite these agreements and meetings, the government has maintained an effective siege of Kobani, which appears to be a means of pressure. This is exacerbated by the presence of large numbers of Kurds displaced from elsewhere in recent weeks. While a number of aid convoys have gone into Kobani, electricity is cut off to the region, which also means water pumps can’t run. To the government’s claim that it has not cut off electricity, but that the problem is damage to the network during the fighting, there seems to be no urgency about fixing it. This is outrageous and the government needs to end this form of collective pressure now.

These and many other issues aside, one way of looking at these new appointments is that this may be the most significant expansion to date beyond the much derided ‘one-colour’ domination of the ruling apparatus, and thus a good sign pointing towards a more inclusive Syria. But once again – we’ll see.

I

Very well done. Relevant, beautifully written and respectable work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much! Feel free to join discussion of the article on my Facebook page.

LikeLike